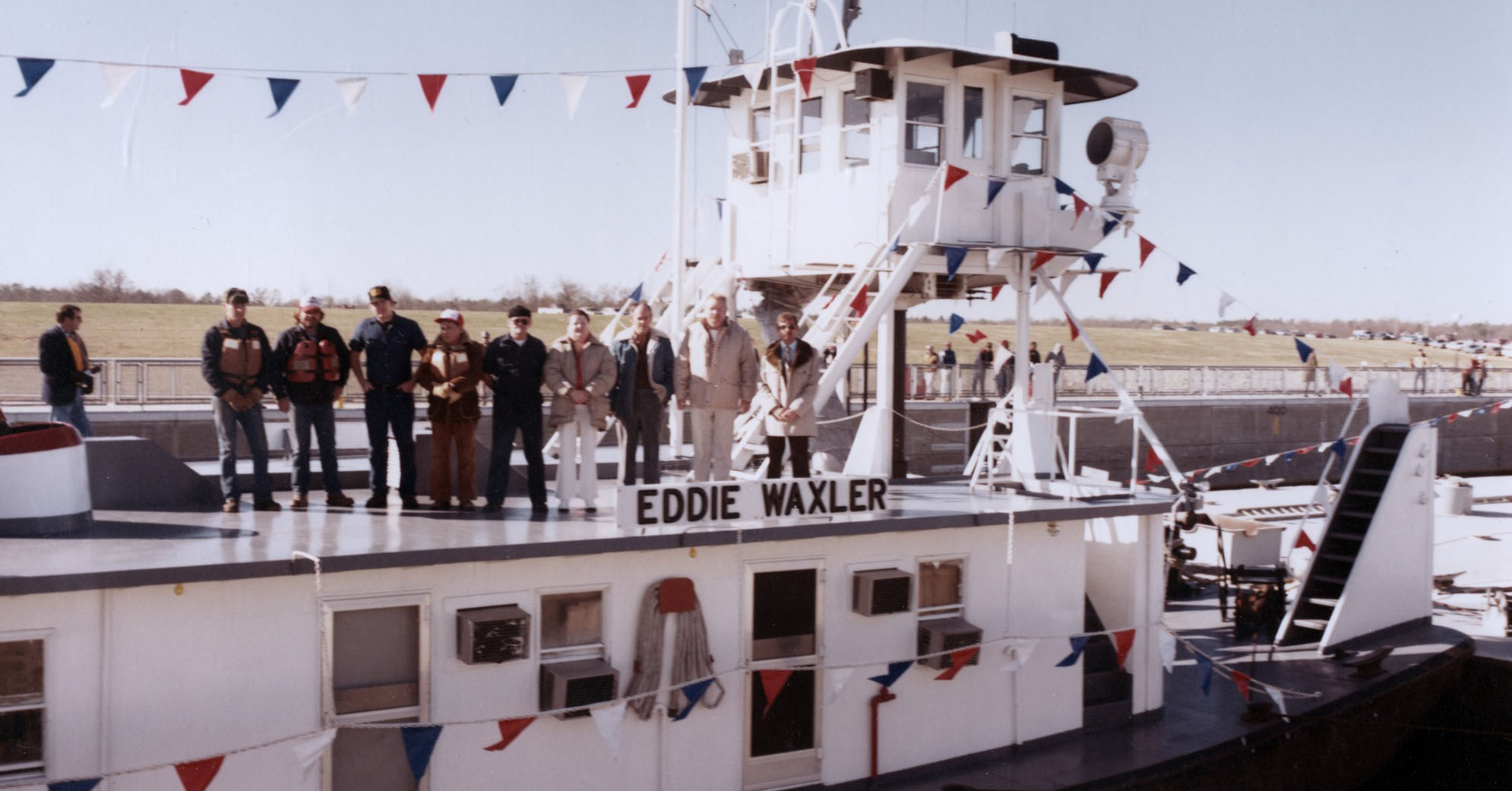

One of America’s newest waterways, the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway (Tenn-Tom), turned 40 last month. Four decades ago, on January 14, 1985, the mv. Eddie Waxler departed Mobile, Ala., and headed up the Tenn-Tom with a tow of tank barges loaded with 64,000 barrels of petroleum products, bound for a refinery on the Tennessee River in Sheffield, Ala.

According to an Associated Press (AP) story marking the occasion, the Eddie Waxler left Mobile at 9 a.m. that morning. The tow was expected to reach Coffeeville Lock four days later and Demopolis Lock on Monday, January 21, 1985. The mv. Eddie Waxler was then expected to exit the Tenn-Tom near Yellow Creek Port in Iuka, Miss., that Wednesday morning and, ultimately, arrive at Murphy Oil USA’s Sheffield refinery at 3 p.m. the same day.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers held a drawing for the inaugural tow on the Tenn-Tom earlier that month.

The AP story cited Bill Kennedy with the Alabama State Docks (now called the Alabama State Port Authority) as saying that Memphis, Tenn.-based Waxler Towing Company, prior to the opening of the Tenn-Tom, would take the Mississippi River from New Orleans up to its confluence with the Ohio River, then down the Tennessee River to Sheffield—a significantly longer route compared to the more-direct Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway. A second AP story from a few days later cited Waxler Towing owner Eddie Waxler as saying the Tenn-Tom shaved 535 miles and five days off the typical travel time between the Gulf Coast and the refinery in northwestern Alabama.

About a month prior to the first tow on the waterway, on December 12, 1984, Corps of Engineers contractors removed the last section of earth, or the “earthen plug,” separating the upper canal portion of the waterway and the Tombigbee River section.

Representatives from the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Development Authority, including current and former administrators Mitch Mays and Don Waldon, respectively, unveiled a historical marker in December near Amory, Miss., to mark the 40th anniversary of the completion of the $2 billion, 234-mile waterway, which involved the excavation of 350 million cubic yards of material. By comparison, construction of the original Panama Canal involved excavation of 268 million cubic yards of material.

Waldon, who was administrator of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Development Authority when the waterway was completed, said he wasn’t actually told about the “mixing of the waters” until the day before it happened.

“They said, ‘We’re going to remove the plug tomorrow,’ and I thought, ‘Really? Well dang, this completes the waterway,” Waldon said. “They removed the plug exactly 12 years to the day after construction began on the lower end of the waterway. They did it in 12 years and for less than $2 billion, and they did it a year and a half ahead of schedule.

“That’s when I became an advocate for full funding,” he added.

Waldon readily admitted that it would be next to impossible to build the Tenn-Tom today with current funding and construction constraints. For one thing, while the entire waterway, with its 10 locks and dams, cost just $2 billion in the 1970s and 1980s, a single lock can cost that much today. Similarly, piecemeal funding drives costs up and completion times out for locks and dams.

Adding to funding and construction stress is the aging infrastructure on the nation’s waterways. The locks on the Tenn-Tom are young compared to most of the system, but above and below the waterway are several structures near the end of their service life. In the past year alone, the Tenn-Tom, the connected Black Warrior-Tombigbee Waterway (BWT) and the main stem of the Tennessee River have all seen unplanned lock closures due to aging infrastructure. Demopolis Lock, located just below the confluence of the BWT and the Tenn-Tom and through which all Tenn-Tom and BWT traffic goes to reach the Gulf, was closed last spring because of a miter sill failure. Farther below Demopolis is Coffeeville Lock, which opened to navigation in 1960. Holt Lock on the Black Warrior River was closed last summer due to cracks in one of the lock chamber’s monoliths. The main chamber of Wilson Lock, located on the Tennessee River near Florence, Ala., is currently closed because of cracking in its miter gates.

Besides those maintenance issues, new lock chambers at Kentucky Lock on the lower Tennessee River and Chickamauga Lock on the upper end of the Tennessee are both well beyond their original budget and delivery schedule.

Waldon pointed to the construction of the Tenn-Tom as evidence of the impact adequate, timely funding can have on a major infrastructure project.

“If we ever want to get ahead of the problem, we’ve got to convince Congress to fully fund these projects when they’re initially approved,” Waldon said.

Besides the navigational advantage of the waterway, with its shortcut between the Gulf of Mexico and the Tennessee, Ohio and Upper Mississippi rivers, Waldon lauded the waterway’s local impacts over the past 40 years. The Tenn-Tom mostly passes through rural communities in Mississippi and Alabama—communities with dwindling populations and limited business and industry.

“The best example is Columbus, Miss.,” he said. “It’s amazing how the waterway has spurred that type of development. It’s a good case study of the regional and local benefits of these waterways.”

Thanks to its connection to the waterway, Columbus has welcomed Steel Dynamics, which operates a flat roll steel plant there. Building on the success of the steel plant, Steel Dynamics is now building a new aluminum rolling mill in Columbus.

Mays also pointed to the growth of Yellow Creek Port at the northernmost end of the waterway and Eviva, a biomass energy company, with both current or planned operations in Amory, Pascagoula, Miss., and Epes, Ala.

“Enviva has the potential to totally change the tiny community of Epes, Ala.,” Mays said.

Waldon added that neither the Corps nor the Office of Management and Budget take into account local economic development when calculating the benefit-cost ratio for projects.

“It’s really a part of the waterway’s story that doesn’t get told,” he said.

Waldon has written a memoir that chronicles both his story and that of the Tenn-Tom Waterway. The book is currently with a publisher, and Waldon hopes to see it in print this spring—well in time for the annual Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Conference, which will be held in Point Clear, Ala., August 13–15.

The Tenn-Tom and the Black Warrior-Tombigbee are in the midst of a study to assess the feasibility of deepening the waterways from 9 feet to 12 feet. Mays pointed to other waterways that are either in the midst of going to 12 feet (MKARNS in Arkansas) or conducting a deepening study (Red River in Louisiana). Mays said, in his view, deepening the Tenn-Tom is essential.

“If we want the Tenn-Tom to remain a viable and competitive waterway, then the deepening has to be done,” he said.

Mays also highlighted an advantage of the Tenn-Tom, which not only was the main motivation for its construction in the first place but also sets it apart from other waterways.

“We’re an alternate route to the Gulf,” he said. “We’re a little different in that regard.”

And as a locking waterway, the Tenn-Tom serves as an alternative to the Mississippi River, especially in times of low and high river.

Ivey To Chair Tenn-Tom Authority In 2025

The Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Development Authority, a four-state compact that advocates for maintenance, business and industry along the Tenn-Tom, has announced that Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey will serve as chair of the authority in 2025.

While serving as governor of Alabama, Ivey has led significant infrastructure investment across the state, including securing funding for the Port of Mobile, the state’s deepwater port on the Gulf, and along both the Tenn-Tom and Black Warrior-Tombigbee waterways.

“It is an honor to chair the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Development Authority this coming year as we continue advocating for this vital link in our nation’s infrastructure,” Ivey said in a statement. “No doubt, the Tenn-Tom Waterway is an asset to Alabama and all compact member states, playing a critical role in supporting commerce and fostering economic growth across the region.

“We certainly have challenges to overcome, but the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Development Authority is uniquely positioned to find realistic solutions, working alongside federal partners and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers,” she added. “I am committed to ensuring our decisions positively impact our waterways and help bolster economic growth.”