Of the discussions I had at industry events the past two weeks, besides President-elect Trump being reelected, nothing got more attention

than inland barge fleets that ply the Mississippi River and Tributaries.

There is good reason to have discussions on barge fleets. They are not expanding, they are getting older, and there are questions about their condition.

Covered & Tank Barges Flat, Open Declining

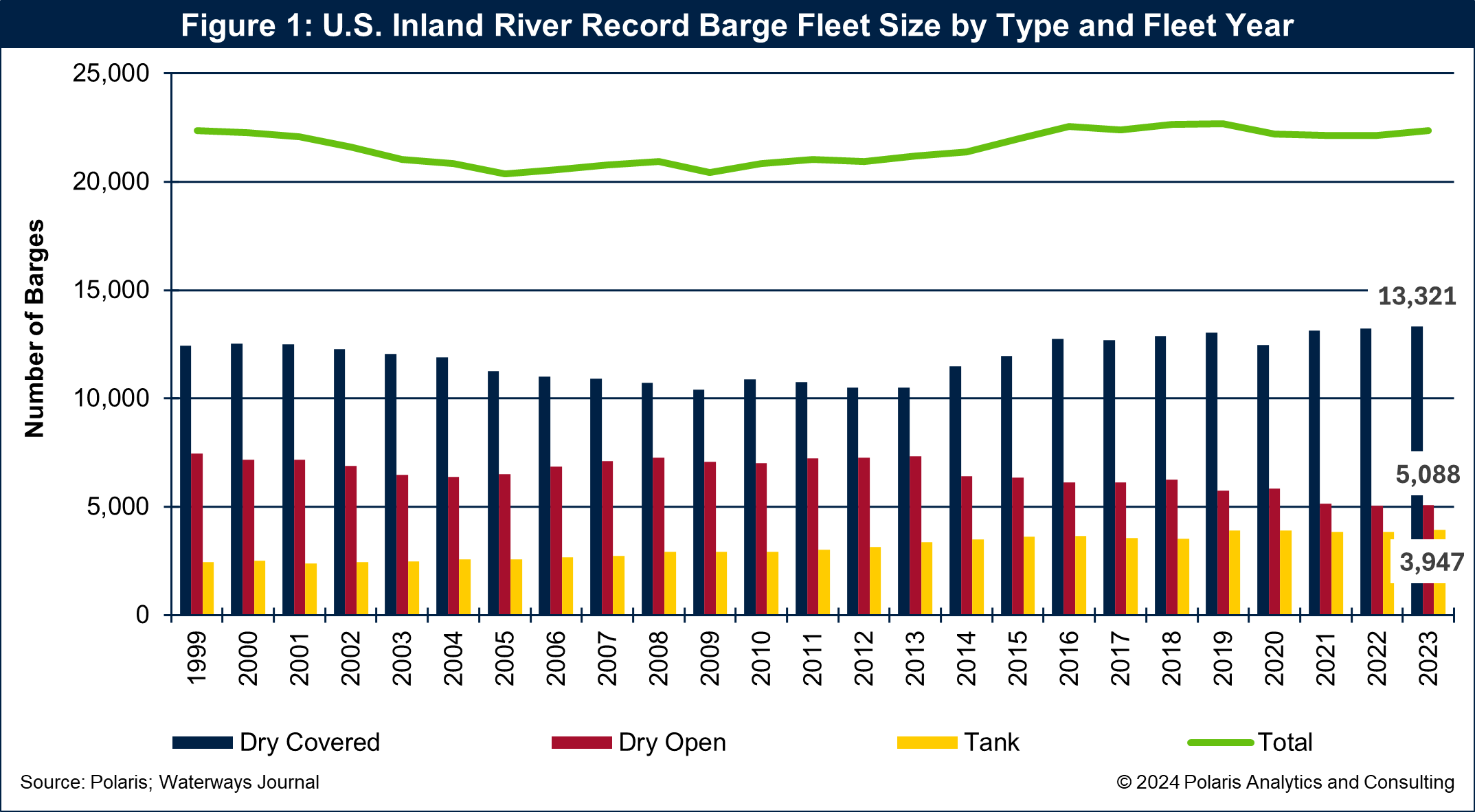

As featured in The Waterways Journal’s “Inland River Record Barge Fleet Profile,” the size of the barge fleet was 22,356 at the end of 2023, an increase of 224 from 2022, yet flat for several years.

The covered barge fleet totaled 13,321 barges at the end of 2023, increasing slightly each of the past two years. The open fleet has been declining since 2018, totaling 5,088 at the end of 2023 as coal movements have been shrinking. The tank fleet has steadily increased as cargo returned following COVID-19, surpassing 3,000 barges for the first time in 2012 and sitting at 3,947 at the end of 2023.

Peeling Back The Onion

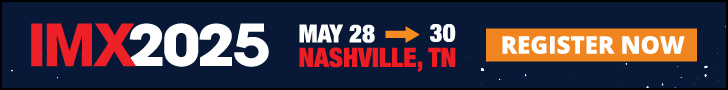

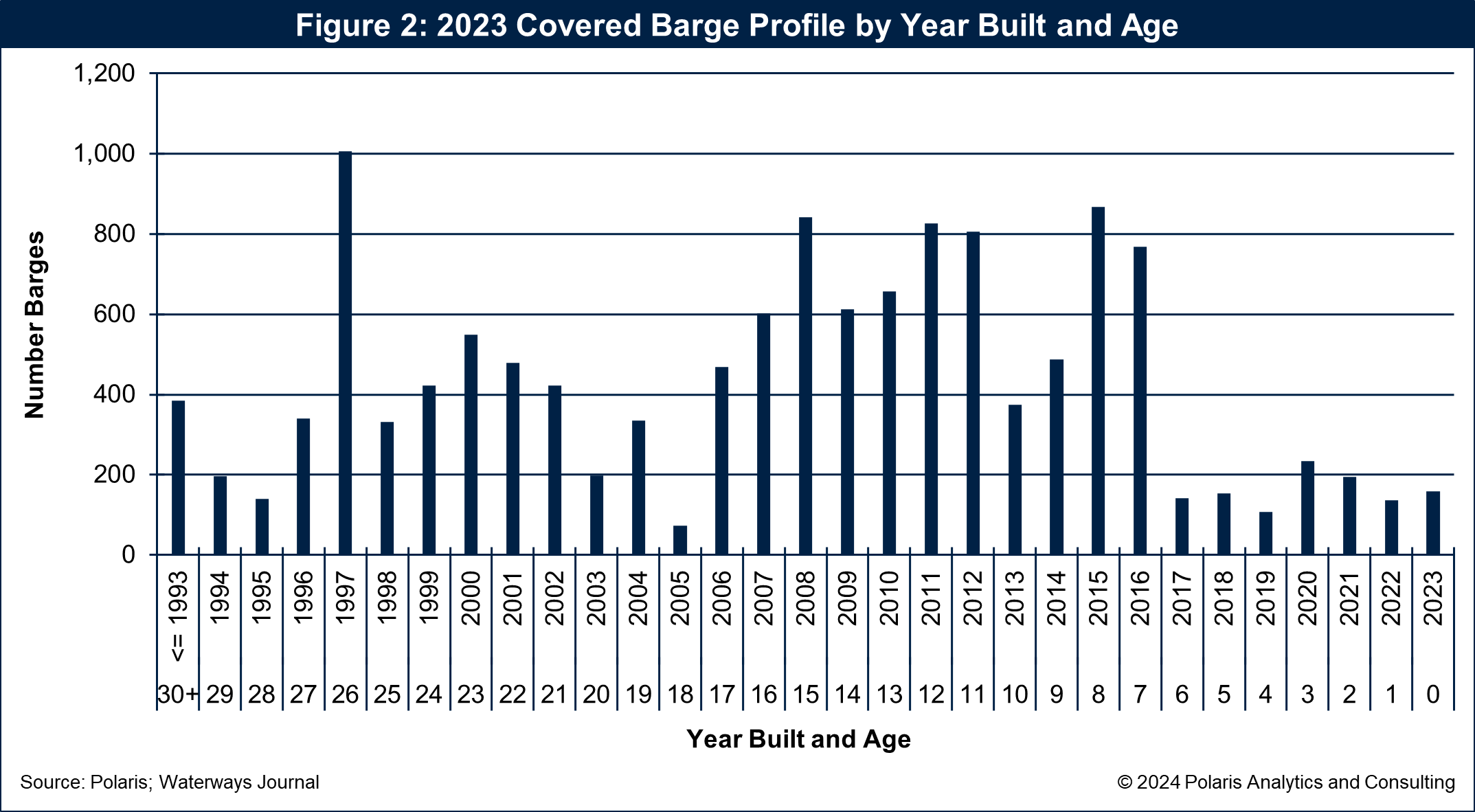

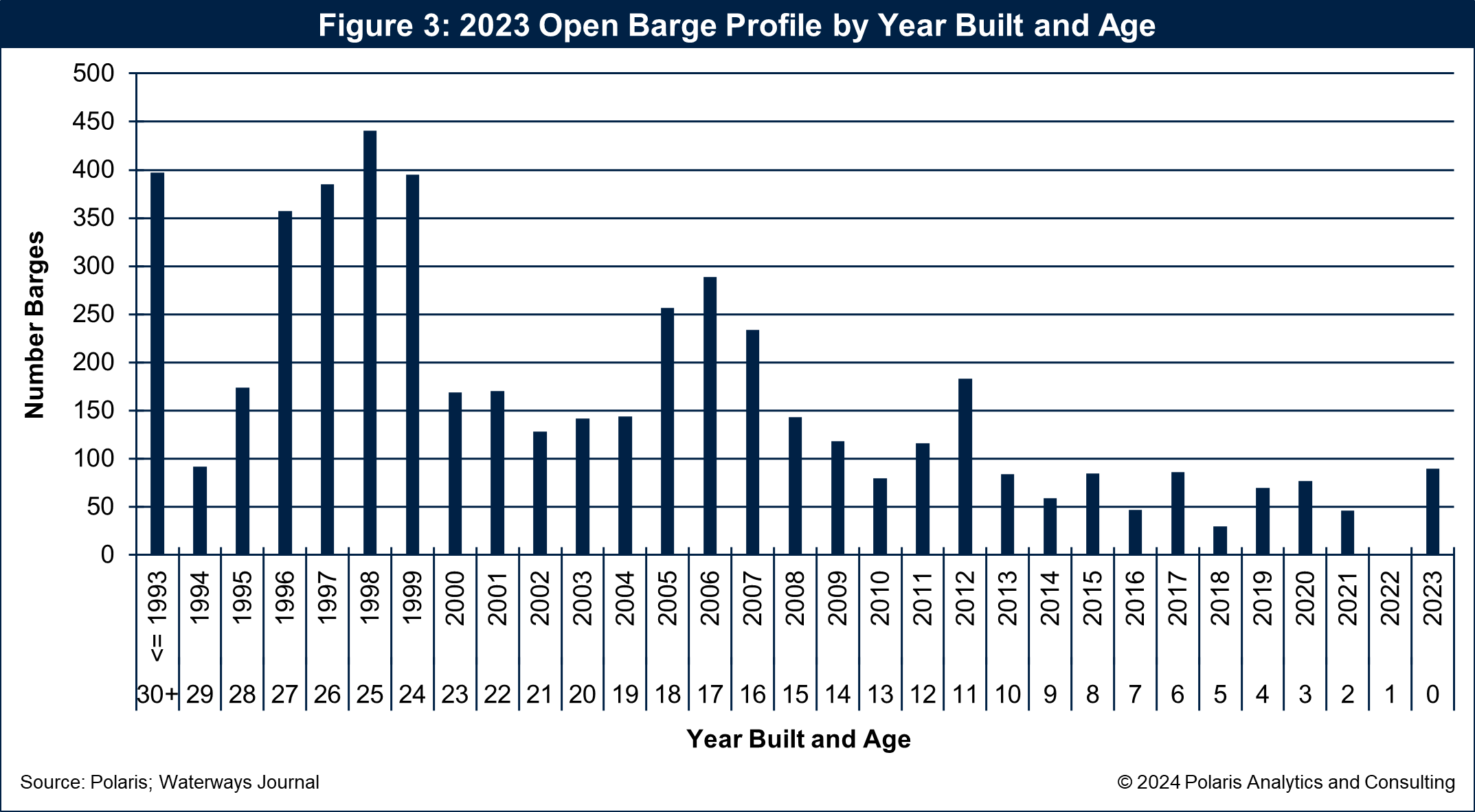

Digging deeper into the barge fleet data reveals unique developments on the horizon. The following three figures depict the profile of each barge type and the number of barges in operation by year built at the end of 2023. For dry barges (covered and open), there have been relatively few new builds of covered barges since 2017 and since 2012 for opens. Tank barges have a slightly different pattern, but there are few new builds in the last three years.

The covered fleet had a steady build program from 2006 through 2016, and those barges represent about 55 percent of the fleet. The fleet older than 2006 represents about 37 percent of the fleet, with a spike of equipment built in 1997. The fleet size from 2017 through 2023, however, represents about 8 percent of the fleet. Without a concerted effort to add capacity and if retirements stay subdued, each subsequent year will bring a fast-aging fleet.

The open fleet is skewed to an older profile with 44 percent of the fleet 24 years and older, 43 percent between 24 and 11 years old, and 13 percent of the fleet built since 2013. The open fleet has been shrinking yet aging at the same time because of a lack of new builds.

Tank barges are unique with four major categorizations, used in specialized services, put in dedicated configurations, inspected by the Coast Guard every five years and under scrutiny by shippers and terminal operators. The number of tank barges built by year has a unique distribution as shown in Figure 4, with a spike of barges built prior to 1992, a peak in 2008 that trails off to 1994 and represents 51 percent of the tank fleet. Since 2010, there were four years with new builds exceeding 150. Their share of the fleet is about 40 percent.

Retire

The challenge for barge owners and operators is when to retire barges. Depending on the barge type there are “general rules of thumb.” Covered barges are generally retired at around 30 years of age, and open barges starting seeing retirements at 25 years. Tank barges have a mixed view, but vetting rules by shippers and terminals want barges 20 years and younger.

There are nuances to these rules of thumb. For example, a well-maintained barge with proper paint or coating extends its life. Replating a dry covered barge with new steel is suggested to add upwards of 10 years to the life of a barge. Permanently removing barges from covered service into open service adds years to the open fleet.

Taking the rules of thumb at face value would suggest 384 covered barges should be retired. Over the coming five years another 2,000 barges will be retired as the barges built in 1997 come into prominent position.

For open barges that are 25 years and older, that would mean 1,846 will be retired. Over the coming five years there will be another 1,000 to be retired. To think that 2,846 barges will be retired over the next five years is preposterous but highlights the challenges ahead in the sector if rules of thumb were followed.

On the tank side, while 20 years is a common vetting age, even if the rule of thumb was 25 years old that would mean 707 tank barges will be retired, and over the next five years an additional 543 will be removed from service. This too is outrageous to consider, but again, it illustrates the misconception of rules of thumb and market realities.

Regardless, retirements are a necessity, especially for assets that have outlasted their useful maintenance lifecycle and are prone to being put out of service for constant repairs.

Replace and Resurge

It is not enough to just retire barges without replacing them. Without replacement, fleets shrink, capacity tightens and freight rates turn higher. With higher freight rates shippers consider alternative routes, modes and sourcing for the commodities, products and goods to run their enterprises.

Other than open barges, there is a need to “resurge” the fleets. Resurge means “to come back or rise again.” In other words, expand and not just replace.

The open barge market has been driven by coal movements that have plummeted but are stabilizing and are supported by longer hauls to export position through the New Orleans Customs District.

With optimism for enhanced energy production in the United States and expansion of biofuels, tank barges have a steady demand growth ahead.

Covered barges support many sectors, especially agricultural commodities such as grains, soybeans, products, fertilizer, lime, etc., cement, steel, salt and many other weather-sensitive cargoes. Expansion of the covered fleet is facing head winds with U.S. crop exports due to increased competition, especially out of Brazil, the risk of another trade war with China and issues with slowing population growth.

Retiring, replacing and resurging barge fleets force stakeholders to consider several economic factors. Steel prices are down, but labor issues continue to be a challenge and the cost of capital is expensive. Still, barge builders have available capacity and capability to build new barges. Yes, building new is expensive, but so too is not building for the future.