U.S mariners reported they have experienced mental stresses from the COVID-19 pandemic, but they are faring about as well as other essential workers, a recent study showed.

The U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System (CMTS) COVID-19 Working Group presented a webinar titled “U.S. Merchant Mariners Mental Health Survey Results” November 22.

The webinar gave results from the Mariner Mental Health Needs During COVID-19 study, conducted independently by Dr. Marissa Baker, assistant professor and industrial hygiene program director at the University of Washington School of Public Health. The study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), CMTS and the Ship Operations Cooperative Program (SOCP), whose members include vessel owners and operators, mariner unions, maritime academies, maritime training institutions, classification societies, other maritime industry stakeholders and government agencies.

The study was based on a survey advertised via social media posts and using a flyer distributed by involved groups. It asked mariners a variety of questions about COVID-19, mental health and their experiences and feelings when aboard a vessel during the challenges of the worldwide pandemic. Participants were enrolled in the study from January 25 through July 31 this year and were not compensated. They self-selected to participate.

A total of 1,559 U.S. Coast Guard credentialed mariners participated in the 15-minute online survey, representing less than 1 percent of all U.S. mariners. Of those, 1,384 had actively sailed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Of those who chose to disclose, 89 percent were male, 83 percent were white, and 87 percent were between the ages of 25 and 64. About 13 percent of the participants were Jones Act mariners. Not all respondents answered all questions. Groups Baker felt were underrepresented included those on harbor tugs, in the dredging and marine construction industries and those working on the Great Lakes. In general, she said, responses tended to skew more toward people on vessels for longer periods of time.

Information was collected in a confidential manner, with no mariner identification data collected. The survey used validated scales to assess the likelihood of participants experiencing symptoms indicative of a major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, high stress, suicidal ideation or post-traumatic stress disorder over the past two weeks to one month, based on their scores from the screening tools. The tools used were similar to scales patients fill out when they go to a doctor’s office.

Study Results

Initial results showed, “Mariners tend to be physically and mentally healthy, which isn’t a surprise because in order to do the job you need to be both physically and mentally healthy,” Baker said.

When asked in general about their physical health, mental health and sleep quality, a majority of mariners rated themselves as in good, very good or excellent condition in those categories. Most also said their conditions were unchanged during the pandemic as compared to before it hit. However, 40 percent said their mental health was somewhat worse, and about 28 percent said their sleep quality was somewhat worse.

When delving deeper, the totality of mariners’ scores on the study questions found 20.7 percent of the mariners surveyed were likely to have a major depressive disorder, just over 22.7 percent are likely to have generalized anxiety disorder and 18.4 percent are likely to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. Of those surveyed, 8.9 percent had scores indicating a likelihood of suicidal ideation or were at risk of self-harm. The highest category, at 38.2 percent, indicated the likelihood of high levels of stress.

More than half of those surveyed had at least one of the concerning mental health outcomes.

“They are concerning levels, but certainly the stress of COVID-19 is being felt by everybody, particularly essential workers,” Baker said.

She also noted that the anxiety rates are less than the level of anxiety reported when compared to the general U.S. population during COVID-19, based on recent research. They have comparable rates of anxiety when compared to other essential workers, including health care workers and retail workers.

Mariners also had comparable rates of depression when compared to the general U.S. population during COVID-19, higher rates of depression compared to U.S. retail workers and lower rates of depression compared to Canadian essential workers.

Comments From Mariners

The study also allowed mariners to make comments, some of which were eye-opening, Baker said.

One reported, “The lockdown has added to the already isolating situation vessel life is. No shore leave and long trips, with possible extensions if crew members don’t show, is very stressful both physically and mentally.”

Another feared for his family.

“I had extended family that got infected with COVID-19 while I was sailing, and I was stressed because of my concern for the family member and knowing I would not be able to come back in a timely manner. It felt comparable to survivor’s guilt in a way. Worst of all, I lacked a support system on the ship, so I was limited to reaching out to family when cell service became available, and I feel like that was fatiguing in and of itself.”

Nearly 70 percent of respondents said they would not be able to start or maintain mental health care while aboard a vessel.

“Mental health care is a literal joke on board,” one mariner said. “There are no accommodations while on board. Even when management explicitly states that mental health care accommodations should and will be made, it is made clear by senior officers that any request will be denied and seen as negative behavior.”

Across the board, Baker said, women reported worse mental health, a statistic also seen in the general U.S. population. Additionally, she said, the 25 to 34 age bracket had the worst risk of mental health outcomes, with the prevalence of mental health outcomes decreasing overall with age. There could be a variety of reasons for this, she said, noting that younger people may be more willing to share their feelings than older mariners, that young people could be facing more stresses with young families at home or that older mariners may be more used to life on board a vessel.

“But it’s worth noting you only get older mariners if you can keep younger mariners in,” Baker said of why the results should be of interest to those of all ages.

Additionally, she said, a longer period of time on board a vessel without leave corresponded with an increase in depression, although it was not clear if one caused the other.

Some mariners expressed extreme frustration about the country’s response while trying to do their jobs well.

“At times like these, the maritime professionals know for sure that our country doesn’t care about our risks we are taking and continue to take to get critical products so that the country can operate,” one said. “Our workforce isn’t as large as most, but we are treated like criminals in our own ports and have no access to vaccines–although we are forced to have repeated contact with people who have been exposed to COVID. To get denied the ability to go ashore, but have four to six shore people come aboard in every port should not be allowed. Obviously, we need better lobbyists.”

Another said, “COVID-19 isn’t the issue; it’s the craze associated with it. I don’t know a single mariner worried about catching the disease, but I know plenty either out of work or can’t leave the boat or house because of stupid protocols.”

Others didn’t trust their employers to have their best interests at heart.

“All the unions and companies care about is keeping the ships running and could care less about getting the mariners home to see their families,” one said.

Another said, “It distresses me the non-support we receive regarding COVID. We are putting ourselves in harm’s way by flying, having pilots and vendors on board and have not even received a letter thanking or acknowledging us. In my 40 years in the industry I’ve never felt more isolated and without company support than I do now.”

Some mariners expressed the opinion that companies appeared to be doing what they could to help during a difficult time.

“The quarantine procedures before and during the first week of sailing, the canceled shore leave and the refusal to allow any persons aboard during the operations were super-effective in keeping the vessels free from COVID-19 exposure,” one said. “With those strict procedures in place, the vessel’s crew could relax, knowing that the vessel was free from COVID-19 exposure. We (the ship) were an isolated unit, which was comforting to all, albeit not without personal hardships.”

Bright spots in the study were that most mariners like their jobs, feel supported at work and are typically very healthy. However, Baker said, the rate of adverse mental health outcomes warrants intervention and ongoing surveillance.

Overall, she said, mariners appear to be frustrated by the lack of shore leave and access to internet and phone. They are concerned about their families and work schedules.

Barriers To Mental Health

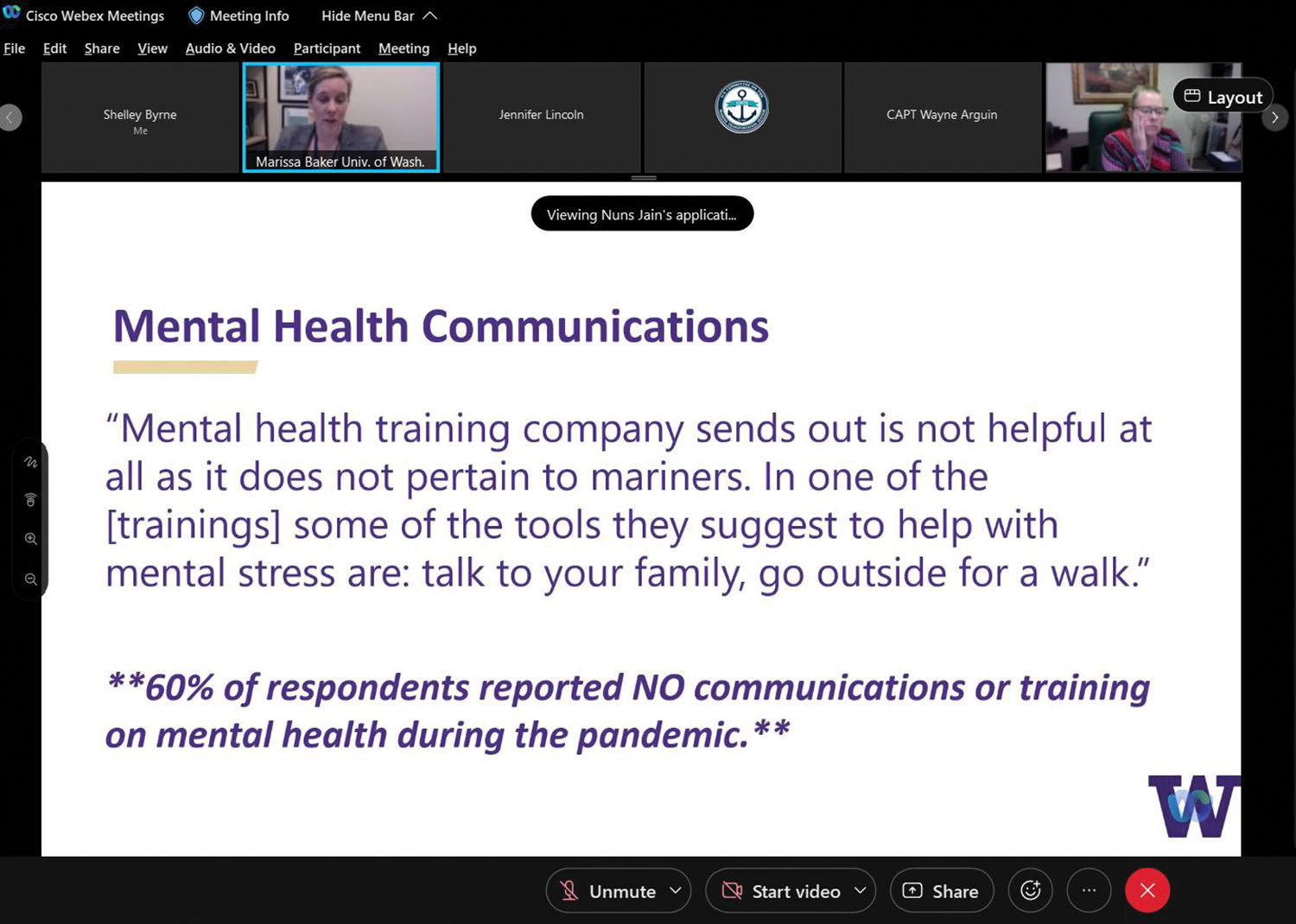

Mariners also noted that the information they had been provided by their companies about responding to mental health needs during the COVID-19 pandemic was not geared toward them.

“Mental health training [the] company sends out is not helpful at all as it does not pertain to mariners,” one reported. “In one of the [trainings] some of the tools they suggest to help with mental stress are: talk to your family, go outside for a walk.”

Sixty percent of respondents reported no communications or training on mental health during the pandemic.

When asked about what types of mental health resource information they would like to receive from the organization they work for during the COVID-19 pandemic, the top scores (tied at 44 percent) were for how to access help if needed and warning signs to look for in crewmates. Forty-one percent wanted to know about what protections or help they have access to through their employer. Thirty-nine percent wanted to know who to contact if they had concerns while on-board. Thirty-eight percent would appreciate strategies to cope with stress. Thirty-seven percent wanted warning signs to look for in themselves. Twenty-six percent of people said they would not like to receive any mental health information.

Mariners also reported in some cases they would be unlikely to seek help. Lack of phone/internet access on board was the top barrier listed by mariners. Other top barriers were concern about how seeking help might affect their USCG credentials, no privacy on board to talk to someone, not how they want to spend their rest time and wouldn’t know how to find a provider.

Recommendations

The study includes multiple recommendations. They include:

• Increase surveillance of mental health in this population.

• Communicate appropriate mental health training.

• Provide mental health care that can be accessed without internet/phone.

• Increase social support on board. (48 percent of respondents said they don’t have someone on the vessel to talk to.)

• Focus on the needs of women, younger mariners and other higher-risk groups.

• Enforce firm reporting policies for bullying/not supporting access to mental health care services.

“I like this because it’s fairly obtainable, and it can have positive results for everybody,” Baker said.

In particular, she said, it might help to begin with social support, such as mentoring programs, which have shown to be beneficial for many reasons.

“Giving people someone to talk to has wonderful benefits, both for the mariner and the employer,” she said.

Full study results are available online at: http://deohs.washington.edu/mariner-mental-health.

Caption for top photo (click on photo for full image): Dr. Marissa Baker of the University of Washington discusses the needs of better mental health communication to mariners as part of a webinar on the results of the study she led on mariner health during the COVID-19 pandemic.