Hurricane Ida made a pair of landfalls at Grand Isle and Port Fourchon in southeast Louisiana August 29 near midday as a strong Category 4 storm. Ida came ashore with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph. and a central barometric pressure of 929 millibars, making it one of the strongest storms to ever make landfall on the Louisiana coast. Towing vessels stationed in the area clocked wind gusts of 179 mph., the strongest ever recorded in the United States.

The storm came ashore on the 16th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina and just two days after the first anniversary of Hurricane Laura, both of which devastated southeast and southwest Louisiana, respectively.

Ida carved a slow path of destruction through southeast Louisiana, devastating much of the bayou parishes of Terrebonne and Lafourche, along with impacts in Plaquemines, Jefferson, Orleans, St. Charles, St. James and St. John the Baptist parishes. The storm maintained much of its strength far inland, with the eye of the storm passing directly over portions of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway and the Lower Mississippi River, where it tossed barges, towboats and ships alike and brought navigation and waterway-based industry to a halt.

As the days passed post-Ida, search-and-rescue efforts transitioned to the long task of assessing damage, reconstituting navigation along the region’s waterways and reopening ports.

“We are working with our federal, state, city, parish and maritime industry partners to reconstitute our ports and our waterways that carry the vital commerce that sustains our nation,” Capt. Will Watson, captain of the port for Coast Guard Sector New Orleans, said September 2. “This is a massive effort, but we’re working collectively to recover.”

As of September 2, the Mississippi River Ship Channel from Mile 105 to Mile 108 remained a “temporary safety zone,” with electrical transmission lines still down across the channel. From Mile 108 to Mile 167.5, the stretch that saw the worst of Ida’s winds, the Coast Guard was allowing waiver requests. According to the Coast Guard, the Mississippi River was open to daylight movements from Mile 105 down to the mouth. Similarly, the Port of South Louisiana remained open with restrictions. Elsewhere, many of the waterways in the region were already open to navigation, with the exception of near where Ida made landfall, including waterways around Houma, the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP) and Port Fourchon.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reported soon after the storm that all the area’s locks and flood-control structures were fully functional and available for when waterways reopen to navigation.

Resiliency On Display

Leading up to and during Ida’s landfall, mariners on towing vessels across the region were able to document weather conditions and their individual experiences while riding out the storm. Crew members aboard the mv. Brittany Lynn were among the mariners who experienced Ida’s wrath where the storm made landfall at Port Fourchon.

The mv. Brittany Lynn received orders August 25 to transport a tank barge from Bourg, La., a small community in Terrebonne Parish just southeast of Houma, down to Port Fourchon, Louisiana’s primary offshore energy service port.

Normally, that would be a pretty fast run, but popup storms, typical for summertime in south Louisiana, delayed the crew’s trip to Fourchon. That, combined with a delay in Fourchon and the closing of a pair of flood-control structures ahead of Ida, meant the crew was forced to ride out the storm aboard the Brittany Lynn in John W. Stone’s slip in Port Fourchon.

“We spent Saturday preparing, because we knew, even if we did leave, we wouldn’t be able to get too far north,” said Shannon Dryden, relief captain aboard the Brittany Lynn.

More Hurricane Ida Coverage:

Ingram Vice President Discusses Hurricane Ida Aftermath

Storm Risk Reduction System Passes Ida’s Test

Pittsburgh District Declares Flooding State Of Emergency

WJ Editorial: Ida Shows Way To Infrastructure Investment

Dryden said he and his crew mates, which included just the captain and a deckhand, secured a block of barges to the dock, with the Brittany Lynn then moored to a pair of barges.

“I got up about 3:30 and made some coffee and stayed mostly in the wheelhouse,” Dryden said. “Throughout the day, it steadily ramped up.”

Dryden estimated the eye wall reached Port Fourchon around midday, and that’s when things got scary.

“As the eye wall was approaching, a couple of offshore tugboats broke loose and got into us,” he said. “They hit the barges we were tied up to on the dock.”

The impact knocked the Brittany Lynn and the two barges loose, and the wind and surge pushed the three vessels about 800 feet to the opposite end of the slip, where they stayed pinned until Ida’s eye moved over Fourchon.

Dryden said he remembers conditions within the eye being fairly overcast, with an eerie radiance and a brief moment of blue sky, but the crew had little chance to truly take it in.

“We took that opportunity to take the two barges back across the slip and get them secured as best we could and get our boat safely secured before the back side of the eye wall came back over us,” he said.

That took about half an hour, Dryden estimates, with the back side of the eye wall reaching them only about 10 minutes after they got back in place. Dryden said the winds and rain didn’t truly begin to calm down until late into the evening.

“What amazes me is, when we were in the thick of it, you really couldn’t see around you,” he said. “Finally around 7 or 8 it calmed down. Then, you could see all the destruction around you. After it was over with, I saw all these buildings 200 or 300 feet from me, and I could see straight through them.”

Dryden said he and his crew mates had a clear plan in place for how to ride out and react to the storm. He said he did his best to reassure his wife of that ahead of the storm.

“‘We’re going to do our best to ride it out, and I’m going to fight like hell,’ was all I could tell her,” he said.

Dryden said he got his start in the maritime industry in 2006 and that he’s been working for Triple S Marine, the Brittany Lynn’s owner, for three years. Besides Ida, the only other storm Dryden has ridden out on the boat was a tropical storm last season. He said he hopes he never has to ride out another storm like Ida again.

“But I think we made the right decision and the best decision with the information we had,” he said.

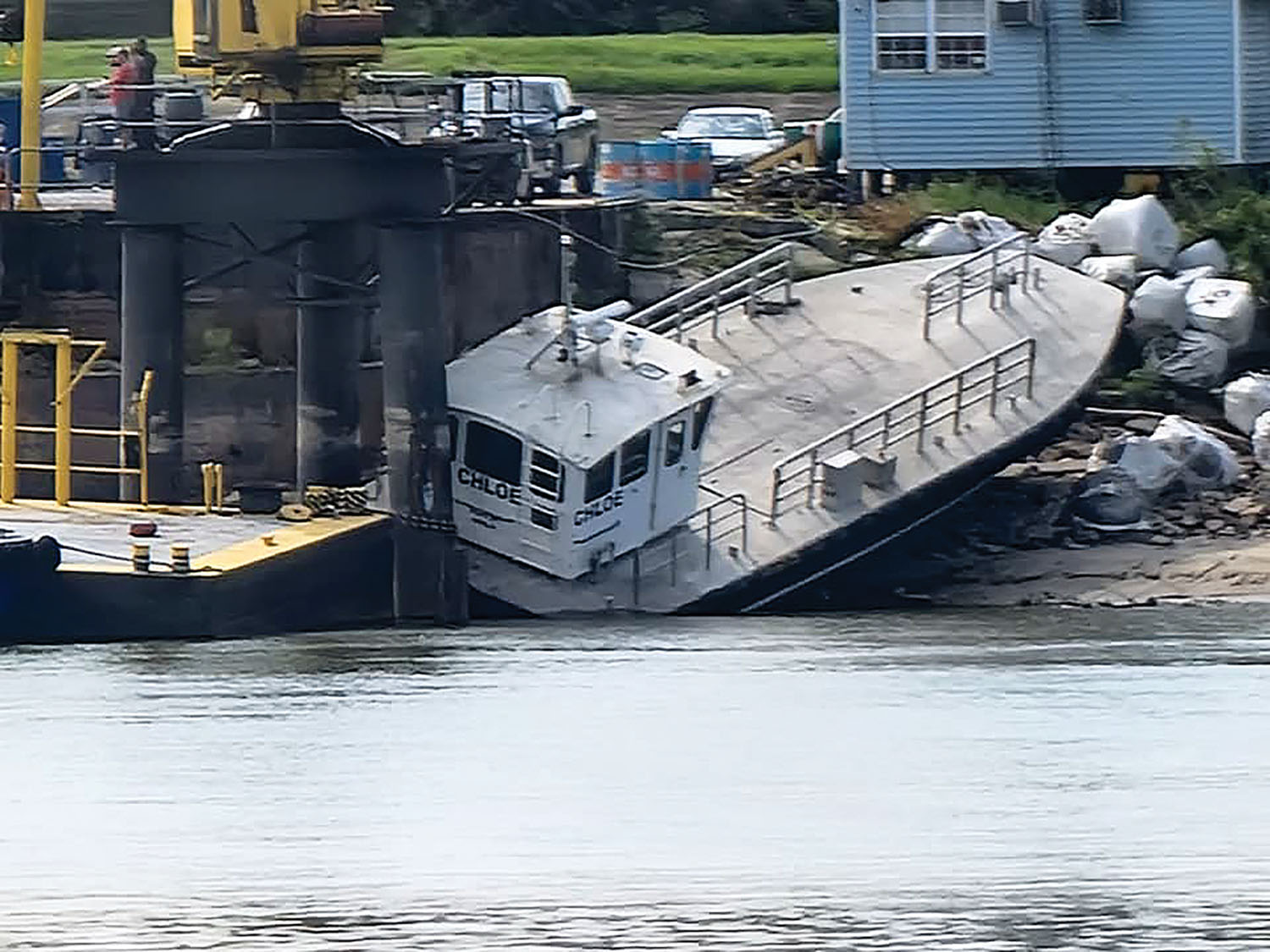

Mariners stationed aboard vessels on the Lower Mississippi River where Ida’s eye passed had an equally harrowing experience, with dozens of barges blown or knocked free, some sinking or even capsizing. Ships in the vicinity of the Bonnet Carré Spillway were pushed aground, with numerous reports of towboats taking on water or aground due to the storm, and damage widespread. Crews in many cases abandoned ship and sought shelter aboard barges. Amazingly, as of September 2, there were no reports of casualties among mariners in Ida’s path.

“To go through those extreme conditions and have no casualties says a lot about the professionalism of our crews,” said Capt. Kenny Brown, a towboat captain, founder of Maritime Throwdown and advocate for mariner training.

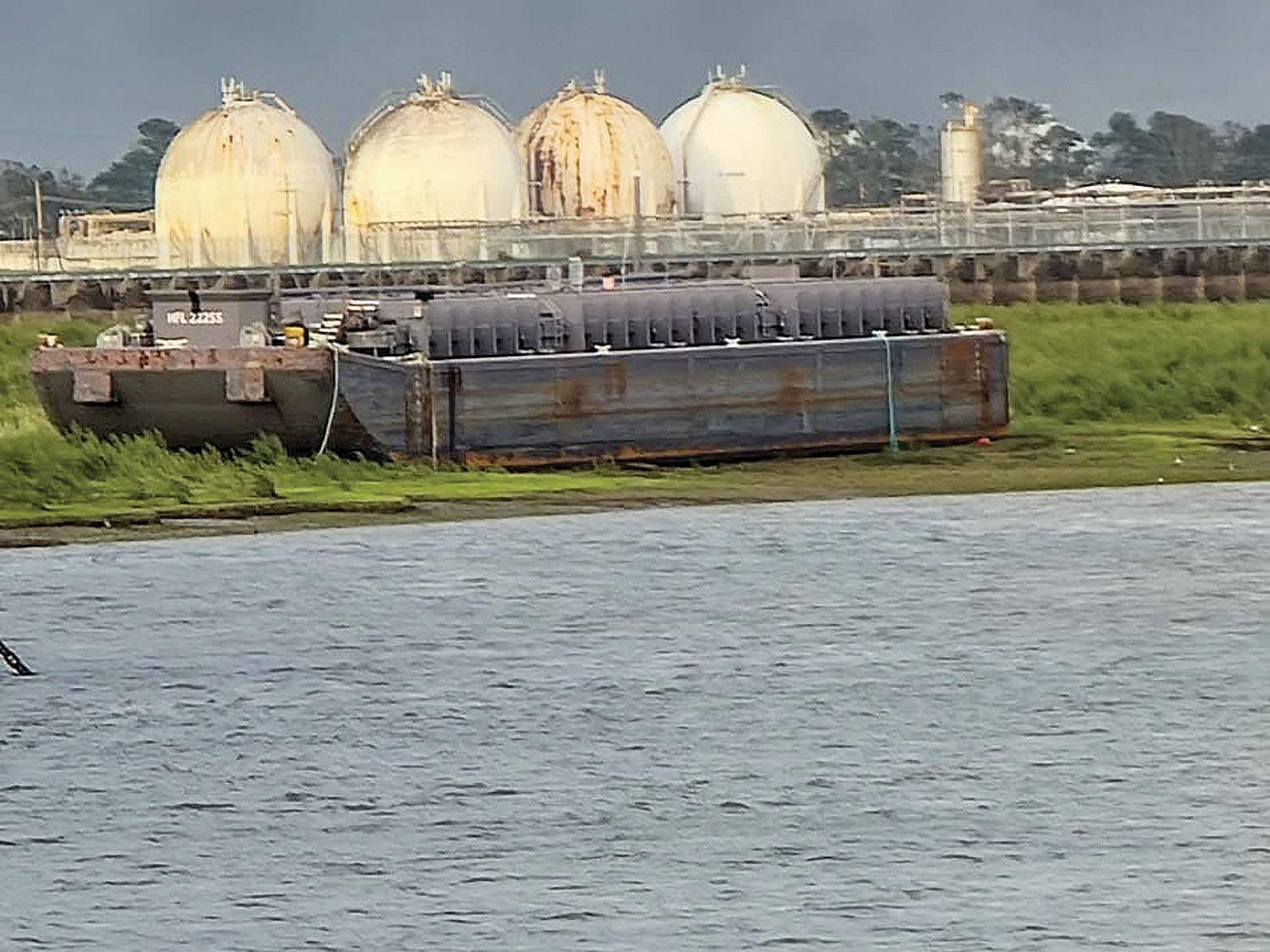

Caption for top photo: Two tank barges left high and dry by the Hurricane Ida storm surge. (Photo by Capt. David Mark Poindexter)

For more photos taken by Poindexter of the aftermath of Hurricane Ida, click on the slideshow below.