knows security.

At 17 years old, Powell joined the U.S. Coast Guard, where he served on the Mississippi Gulf Coast for four years. From there, in 2004 at the age of 21, Powell was accepted to the U.S. Secret Service. During his time with the Secret Service, Powell served on the dignitary detail, where he protected representatives of countries like Israel, Egypt, Belgium and Niger. For three months during the 2004 presidential campaign, Powell was part of then-U.S. Senator and presidential candidate John Kerry’s campaign. He also spent two months as part of President George W. Bush’s campaign detail.

After three years in the Secret Service, Powell left to join Maritime Defense Strategy LLC (MDS), a company he purchased and became president of in May 2009.

Since that time, MDS has grown into a leading maritime security consulting firm, partnering with companies to develop more than 250 facility security plans, facilitating more than 2,000 security drills and training more than 1,000 maritime professionals.

Powell brought his knowledge of security within the maritime field to IMX 2020, with a session titled “Vessel and Facility Security: Cyber Security with TWIC Evaluation.”

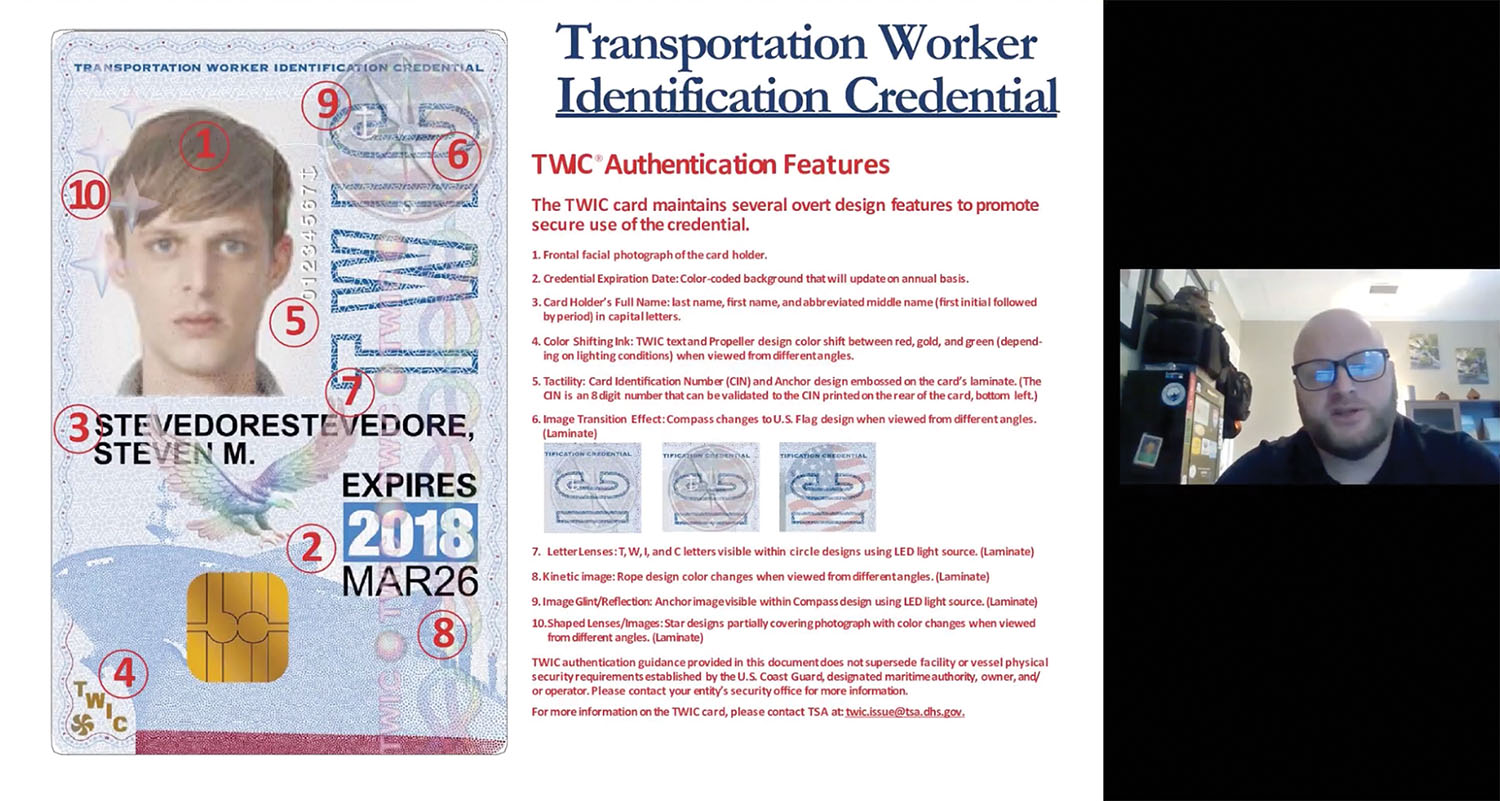

“TWIC” stands for “Transportation Worker Identification Credential,” an identification card required in the Maritime Transportation Security Act for workers to enter certain maritime facilities and go aboard commercial vessels.

Powell first overviewed basic regulations related to TWIC cards, including instances where a TWIC is not required to board or work adjacent to a vessel. One example is that federal officials, state and local law enforcement, and emergency responders do not require a TWIC card to board a vessel or access a facility.

“For federal officials, which includes any employee of the federal government, they only gain unescorted access during the course of their official duties,” Powell explained.

However, federal officials must present their own agency credentials, with crews logging the visit. In contrast, if a law enforcement officer is working as a port security officer while off duty, he or she would need a TWIC card.

Emergency responders must be responding to an emergency to board a vessel without a TWIC card.

Powell discussed some important security features of TWIC cards, including microprinting, or printing smaller than what typical printers are capable of, and black light reflective images. Despite those security features, TWIC cards have been subject to tampering and sale, sometimes by laminating a new photo onto the card and placing it in a lanyard. Power gave the example of a truck driver with a drug conviction needing a TWIC card to access a port but nonetheless unable to get one legally. Powell said, oftentimes, falsified or altered TWIC cards go unnoticed at points of entry.

“Only 50 percent of guards ever look at the actual name and compare it with the bill of lading or a second form of identification,” Power said.

The old cards also were susceptible to having the expiration date altered, which was one of the weak points addressed in the new, redesigned card. Old versions of the card will remain valid until 2023, or until their expiration date. In the current version, rather than the date in bold print on a white background, the expiration year is in relief within a colored box. The color of the box changes by year, further discouraging forgery. There are also additional holograms and features visible using an LED light source.

Besides discussing details of valid TWIC cards, Powell also touched on steps to take if a TWIC card is suspected to be invalid. Because a security official cannot confiscate a person’s TWIC card, he or she should instead make an effort to take a photo or otherwise preserve a record of the forged or expired card.

“If directed by the Coast Guard, ask the individual to stay at the access control point or alongside the vessel, but still don’t allow him aboard the vessel or in the facility,” Powell said.

The owner or operator of the vessel or facility is not required to attempt to prevent the person from leaving, if he or she desires.

“If the person wants their TWIC card and wants to leave, then you know they had bad intentions and there was no way they were going to stick around for the Coast Guard or law enforcement,” Powell said.

Powell said companies should have language in their vessel or facility security plans related to fraudulent TWIC card presentation.

TWIC guidance is available online on Homeport.

Cyber Security

Powell then pivoted to discuss cyber security. While cyber security concerns don’t always connect directly to vessel operation, Powell said, cargo movement statistics in the United States nonetheless mean that what impacts ports and terminals will impact the movement of vessels.

“We have to remember that 75 percent of all U.S. commerce in one way, form or fashion is transported via the maritime transportation system,” he said. “Ninety percent of the world’s trade is done through the maritime transportation system.”

Powell mentioned cyber attacks that have impacted operations at the Port of Rotterdam, Germany, Maersk Line and ADM.

“These are all cyber attacks that could’ve been prevented if we had cyber hygiene or cyber protocols in place,” Powell said. “Now those are going to come to fruition.”

The Coast Guard, Powell said, has announced that cyber security must be addressed in vessel and facility security plans by September 2021.

Powell ended his presentation by overviewing cyber security attacks and examples of cyber security vulnerabilities. Powell emphasized the importance of securing a vessel’s information technology systems, noting that cyber attacks now can even access and control a vessel’s navigation system.

Regulations relating to cyber security guidance are outlined in 33 CFR Parts 105 and 106.