Morgan Line Brought Numerous Innovations In Cargo Handling

More than 100 years ago, there was a waterways transportation company that brought innovations in freight- and material-handling, expediting and dispatching to the ports of New Orleans, Galveston, Houston and New York. By the end of the 19th century, the company was part of a nationwide multimodal passenger and freight system, with steamships, tugs, barges, paddlewheel steamboats, trucks, trains—and its own custom-designed wharves and terminals.

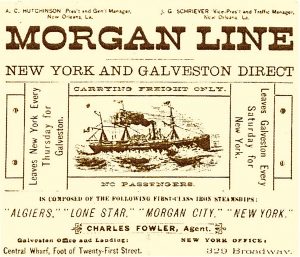

This was the Morgan Line, and later Morgan’s Louisiana & Texas Railroad & Steamship Company (ML&T). It eventually became part of the Southern Pacific Railroad system.

Charles Morgan (1795–1878) was a New York businessman who brought some of the first steamships to the Gulf Coast. As early as 1835, he had a wood-hull steamship running from New Orleans to Galveston, when Texas was still part of Mexico. In the 1840s, he had two or three ships on scheduled runs there. Over his lifetime, he owned more than 100 steamships, probably more than any one person in history.

A few years after the Civil War, Morgan bought the fledgling railroad running from Algiers, La., to Brashear, La. (later called Morgan City). Morgan was not really interested in railroads as such. Water transportation was his forte. He only saw the new-fangled railroads as a way to bring regional freight and passengers to his steamships.

He also started a New York-to-New Orleans steamship service, with four steel- hull propeller-driven steamers—the Lone Star, Algiers, Morgan City and New York—each about 2,300 gross tons. They were used for freight only.

Morgan himself didn’t live to see it, but in 1883, the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP) completed its route from California and bought the ML&T, including the Morgan Line steamers and other marine assets. Now the SP could offer through service from California to the East Coast—by rail to Algiers, then by ship to New York. The marine part of the business kept the Morgan Line name.

Cargo-Handling Innovations

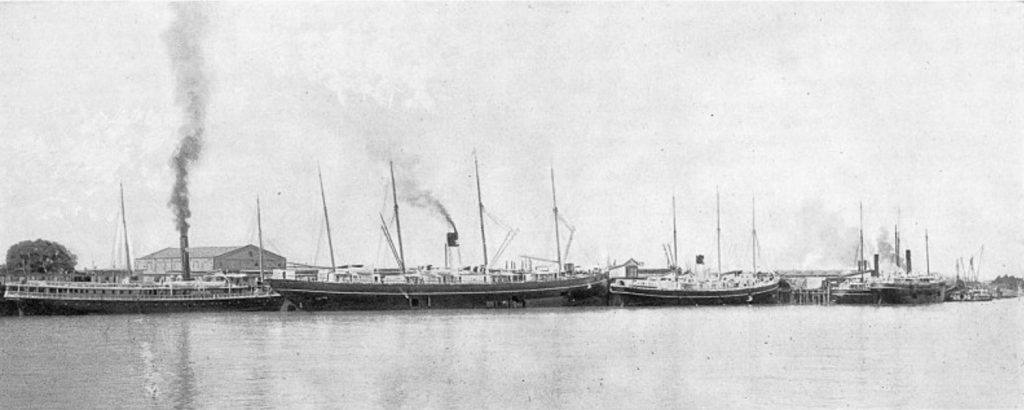

By the early 1890s, the Morgan Line had a dozen steamships running from New York to Algiers. Some of them carried passengers; all of them carried freight. The increase in cargo handled at Algiers was phenomenal. The way they handled it was an impressive combination of labor, ingenuity and technology. The ships themselves were custom designed and built with two or three cargo hatches on each side of the hull, in addition to two traditional hatches up on deck.

A ship from New York arrived every day, coming in through South Pass and tying up at Algiers at midnight. The location is right by today’s Cooper/T. Smith landing at Mile 93 AHP. The Morgan wharf was 2,000 feet long and 150 feet wide, almost all of it covered by sheds.

As soon as a ship was secured, Morgan tugs put deck barges on the outboard side, ready to receive cargo out of the side hatches.

At 6 a.m., hundreds of men, usually between 800 and 1,000 strong, descended on the ship. Some teams manned the outboard barges, others took freight directly out of the inboard side, putting it on steam-powered trucks to be hauled across the dock and transferred to boxcars. Still more crews manned the dockside steam crane hoisting cargo up out of the deck hatches and putting it directly into train cars on multiple tracks on the dock itself.

The wharf even had one or two “endless freight conveyors,” a new contraption designed, marketed and installed by the Link-Belt Machinery Company of Chicago. It was not a rubber conveyor belt, but a series of metal bars linked together, 48 inches wide, with metal blocks at intervals to hold cargo in place.

All this off-loading and loading would take place in the middle of other dock and yard activity, including a double-track railroad transfer steamboat shuttling back and forth to the east bank, plus stockyards and a cattle ferry toward the upriver end of the wharf, not to mention the bustling, fully equipped railroad yard itself on the land side of the levee, with hundreds more men and women building and repairing train cars and locomotives. Also in the mix was a small passenger terminal.

But by 8 p.m., the ship was expected to be loaded with eastbound cargo and ready to get underway. The Morgan ships were rarely behind schedule. The voyage between Algiers and New York usually took 5½ days. Altogether, shipments in the 1890s from California to New York would take 14 to 16 days.

New York Wharves

Prior to 1910, the Morgan Line’s New York wharves were down toward the southern end of the harbor, on the North River (or Hudson River) abeam Lower Manhattan. It was well-organized, but eventually a little cramped. Cargo bound for New Orleans and Galveston was deployed at Pier 25, while incoming cargo was routed through Piers 34 through 38, near where the Holland Tunnel is now.

In April of 1910, they moved to more spacious quarters about a mile upriver at Piers 48 through 52, near today’s Whitney Museum. Pier 48 served as a passenger terminal for the larger Morgan steamers that carried both passengers and freight.

The new location gave the company twice as much space—more than 476,000 square feet, most of it covered—but it also provided an opportunity to incorporate some new time- and labor-saving designs. The piers were modified with adjustable drops extending through the apron of each dock, to facilitate cargo movement at different tide levels. The tide range at New York can be as much as 7.6 feet.

Three of the new piers were designated as discharge piers, each one double-decked. Dispatchers could pre-position cargo at specific locations, knowing which hatch on which ship would be where. Items to be hoisted and lowered through a ship’s main deck hatches were positioned on the dock’s upper level, while freight on the lower level could be rolled directly into the ship’s side hatches.

In 1914, the company bought a fleet of electric trucks to be used on the docks (at New York as well as New Orleans). This was at a time when a number of manufacturers had started producing electric automobiles, which were becoming quite common. Detroit Electric, among others, produced hundreds of industrial electric trucks that proved popular for local deliveries and stop-and-go city traffic. The Morgan Line used the electric trucks for long hauls between piers and for moving freight in and out through the ships’ side hatches.

In 1916, the New York docks were modified again by installing freight elevators. Two electric elevators each were built into Piers 49, 50, and 51. Each elevator had a two-ton capacity, and could carry one of the electric trucks loaded with freight.

Galveston

The Morgan Line, and Charles Morgan himself, had had an on-and-off relationship with Galveston, abandoning it at least twice in favor of the upstart Buffalo Bayou port near the small town of Houston. In 1900, though, the SP began building what it called “the finest piers in the country” at Galveston. The company line was that the transcontinental trade was so busy that both New Orleans and Galveston ports were needed.

A New York to Galveston steamship line was introduced in 1902, with three steamers per week. They used what was called Berth B, which was the farthest berth to the west, near where the Pelican Island Causeway is now. The pier was 700 feet wide on the channel end, and 1,250 feet long on the east and west sides, with room for up to five steamships.

The wharf had a little more than a quarter million square feet of storage shed space. There were seven railroad tracks running the length of the pier. The tracks themselves were below dock level, leaving the boxcars’ floors at platform level. Freight coming off the ships could be rolled right into waiting boxcars. These loading bays or platforms could hold up to 128 train cars.

Train cars with eastbound or outbound cargo were positioned right alongside the ships. Heavy or bulky freight was transferred by derrick barges. There were relatively short dockside ramps to accommodate Galveston’s minimal tide range. Other than that, there was not much in the way of mechanical or technological input needed, since 95 percent of the freight was simply transferred directly for continued shipment east or west.

Changes In New Orleans

Back in New Orleans, things were changing. Once the Galveston docks were in place in 1902, and eight of the New York-to-Algiers steamships were redirected there, the Morgan Line began transferring its New Orleans operations from Algiers to the east bank. Specifically, they procured 2,000 feet of river frontage stretching from Conti Street to St. Philip Street. This was about half the length of the French Quarter, from just below the present-day Aquarium of the Americas to two blocks below Jackson Square. It was centered on Toulouse Street, where the steamer Natchez ties up now. There was enough river frontage to accommodate four Morgan steamships.

Unfortunately, there were problems. The Morgan operation had gotten used to the high-tech “latest designed apparatus” at Algiers, with its “endless string of sheds.” Toulouse Street, by contrast, was bare-bones, with no protection from the weather, no sheds, no modern freight-handling devices.

In 1904, after much haggling, the Southern Pacific Company advanced the New Orleans Dock Board $175,000, which would be worth about $4.5 million in 2018. The bulk of the money was to finance construction of a steel shed covering nearly the entire length of the wharf. The finished wharf included double railroad tracks running the entire length, so that cargo could be transferred cross-mode.

The new shed was a forerunner to the ubiquitous and seemingly endless steel-clad wharf sheds that would soon stretch nearly 10 miles along New Orleans’ east bank from Alabo Street to Henry Clay Avenue.

When electric trucks were introduced here in 1914, they caused quite a stir. According to one reporter, “The electric trucks are handy little devices, whose rapidity of movement excite wonder…. [The] movement of a lever would cause the truck to dart backward, stop instantly, and then dart forward….”

Houston Ship Channel

Finally, back in Texas, the Morgan Line also ended up with a Houston-area steamship terminal. Charles Morgan himself had worked for a deep-water channel to Houston, dredging a preliminary cut at Red Fish Bar, and, in the late 19th century, bringing in a fleet of dredges to dig the shortcut channel at Morgan’s Point (which is named for an unrelated Morgan). Charles Morgan is sometimes referred to as the father of the Houston Ship Channel.

In 1876, the Morgan Line brought the first oceangoing steamer up Buffalo Bayou to their new docks at Clinton, on the north bank just above the mouth of Sims Bayou. This was just across the slip from where Houston Cement has its west terminal now. Morgan built an 8-mile railroad line to connect the new docks to other railroads at the town of Houston.

This operation was soon overshadowed by a deeper channel at Galveston. In the 1920s, though, an improved Houston Ship Channel lured business back. In 1926, the Morgan Line completed an improved, “modern, fireproof” terminal at the same Clinton site.

World War II

The far-flung operations of the Morgan Line and the Southern Pacific lasted for decades, but World War II marked the end of the Morgan steamships. Uncle Sam took the ships for the war in 1941, and they were built so well that the government kept most of them after V-J Day.

Pier B in Galveston is still there, and still served by the same railroad connection, but it’s a sulfur transfer dock now. The circa 1926 Clinton terminal on the Houston Ship Channel eventually became the site of a large Kinder Morgan terminal.

The North River wharves on the Manhattan waterfront are gone. All that’s there now is the scenic Hudson River Greenway.

The post-1902 east bank New Orleans terminal long ago gave way to the aquarium, Woldenburg Park, the steamer Natchez, and the Moonwalk. Across the river, the site of the once-bustling Algiers terminal is where you’ll find Smith’s Fleet. There’s no steamship landing, and there’s no railroad, but old-timers in the Algiers neighborhood still refer to the area as “the SP yard.”

Dan Hubbell is a freelance writer living in Berkeley, Calif.