In March 2018, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers St. Paul District released the Draft Feasibility Study Report and Integrated Environmental Assessment for the Pigs Eye Lake project in Ramsey County, Minnesota. For the last two years, under the Continuing Authorities Program (CAP) Section 204, the Corps has studied the beneficial use of dredged material to improve aquatic habitat, create wetlands and slow shoreline erosion at the shallow backwater lake. The tentatively selected plan calls for a complex of seven islands with approximately 16.3 acres of floodplain forest and wet prairie habitat and 17.6 acres of marsh habitat.

Pigs Eye Lake is a 638-acre lake, southeast of St. Paul, Minnesota, within Pool 2 of the Mississippi River. Although Pigs Eye is called a lake, it is technically a large riverine open-water floodplain. “It used to be marsh before the impoundment. Over the course of many years, a lot of what used to be vegetation is receding back to the shoreline and continuing to do so under the pressures of the wind fetch. That shallow nature of the depth makes that worse,” said Aaron McFarlane, biologist with the Corps St. Paul District. Wind fetch is a measure of the distance wind can travel in a constant direction across water without encountering an obstacle.

Pool 2 of the Mississippi River links the upstream ports of Minneapolis, St. Paul, the Minnesota River, and the remaining Mississippi River navigation system downstream. The most important commodities hauled are farm products moving from local terminals in St. Paul and on the Minnesota River to the Gulf for export.

The Pigs Eye Lake area is managed by the Ramsey-Washington Metro Watershed District, and the project lies within the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. The majority of the lake and riparian area is owned by Ramsey County.

On October 17, 2012, the Corps received a letter of interest from Ramsey County Parks & Recreation. The county wanted to act as a sponsor and requested that the Corps perform a study to determine the feasibility of restoring aquatic habitat through the creation of islands in Pigs Eye Lake. Funding for the study came under the Beneficial Use of Dredged Material (Section 204 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1992). The study began in January 2015.

Continuing Authorities Program, Section 204

Section 204 provides authority for the Corps to restore, protect and create aquatic and wetland habitat in connection with the construction or maintenance dredging of an authorized federal navigation project. Section 204 for the beneficial use of dredged material is one of a number of existing authorities in CAP, which also addresses flood control, shoreline protection and aquatic ecosystem restoration. Under Section 204, the federal government covers 100 percent of the study costs. For the project costs, the federal government pays 35 percent with a maximum of $10 million. CAP projects require local sponsorship and cost sharing, but water resources projects can be implemented without additional project specific congressional authorization.

The Pigs Eye Lake project would be the first Section 204 project for the St. Paul District. The project was also very unique for the area and required the St. Paul District to ask around for help. “It’s unique to our district for sure. It required us to reach out of our expertise in-house and obtain other opinions,” said Nate Campbell, project manager for the Pigs Eye Lake project and program manager for CAP at the St. Paul District.

According to the feasibility study, the current Mississippi River channel adjacent to Pigs Eye Lake was cut during the draining of Glacial Lake Agassiz via Glacial River Warren 11,700 and 9,400 years ago. During the time when the glaciers waned, large amounts of sediment deposited by Mississippi River tributaries acted as natural dams, creating a series of lakes upstream and likely leading to the clays deposits on the western portion of Pigs Eye Lake.

The feasibility study also concluded that the construction of locks and dams upstream and downstream along the Mississippi did not have significant effect on the sedimentation patterns of Pigs Eye Lake. However, development to the north and west of the lake had impacted sedimentation on the lake. Development cut off channels and rerouted others and ultimately increased the rate of fine particle sedimentation in the lake. The lake itself does not have a lot of flow to and from the Mississippi River. It is only affected by the Mississippi River in times of high flood.

The land area northwest of the lake contains inactive wastewater treatment ponds, owned by Metropolitan Waste Control. To the north, there is also a 300-acre site of the former Pigs Eye Landfill, which is a Minnesota Superfund site, under the Minnesota Pollution Control Program program.

Extensive testing was done on the lake sediments and potential contamination. “We were really looking for broad level agency agreement that the project wasn’t re-exposing contaminants. The results of our sampling certified that,” Campbell said. He said the Pigs Eye Lake island work has also spurred momentum with restoration at the Superfund site.

“It’s been a shallow lake as far back as we can get data on it,” McFarlane said. “I was able to find some newspaper clippings from the 60s and 70s, when there was other development under consideration, and it was similar lake conditions, super muddy, super turbid.”

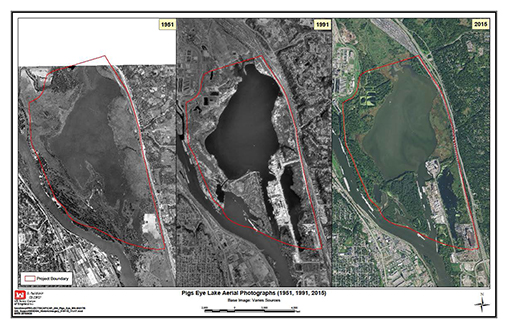

Pigs Eye Lake is in the middle portion of Navigation Pool 2 and somewhat unique as one of the few backwater areas in the upper portion of the Pool. However, the composition of the lake has changed over the years. The lake’s loose, mucky bottom, long fetch and shallow depths have intensified erosion issues that began with development. “The development around the area, made it no longer function as a shallow marsh system,” Campbell said. As the vegetation receded and wind fetch increased, the lake got murkier, and the cycle exacerbates erosion issues and habitat loss on the lake.

Approximately 18 acres has eroded in the last 24 years, which equates to a 0.75-acre loss per year. That erosion rate would continue without a project, climbing to 37.5 acres over the next 50-year period.

Designing the Island Structures

To stop the erosion, the St. Paul District examined many different options and structural elements – sand blankets, islands, sand benches, marsh creation and even pothole dredging. The later, which involved dredging various sized “potholes” in the lake bottom, was pulled from consideration because of the high risk that a dredge cut in the lake could not be sustainable and likely susceptible to sloughing, causing the sides of the dredge cut to fail.

A sand blanket (or a thin layer of material over the entire lake substrate) could be effective, McFarlane said. However, on such a big lake, the option was not economically feasible. A sand blanket would also not do anything to reduce wind fetch or increase upland habitat.

Island creation would serve a variety of purposes in creating habitat. In part, they help protect shallow areas from wind and wave action and further erosion, protecting vegetation and improving conditions for more species.

A sand bench or a smaller-scale version of a sand blanket, would be also be used in the selected plan, incorporated into the islands to extend the shallower habitat surrounding the islands. They are formed by extending sand placement below the water surface adjacent to the island features. The wide base of the island remains underwater and provides additional sand bar habitat.

A wider base and larger sand bench was considered, but because of cost constraints, it was scrapped. Also, the Federal Aviation Administration and the Metropolitan Airport Commission were concerned about sand benches. The increased area provided loafing habitat for large water birds, such as Canada Geese and American white pelicans. These species are a concern as airport hazards.

The original concept started with a nine-island design, which significantly exceeded the funding threshold for the project. Initial island designs, according to the feasibility report, also did not adequately reduce wind fetch. With long-term wind data from the local airport two miles away, combined with temperature and climate data, the Corps team began tweaking the island design in an attempt to reduce the amount of dredged material required and project cost, while still meeting project goals.

“We started with a large island design and we worked down, so the design was still able to block the main directions of the wind and provide some shelter areas,” McFarlane said.

The final island design included seven island, and three split island features, which provide a more sheltered area in the middle of the island, using similar amounts of dredged material, compared to a typical island shape. The protected area is more likely to grow aquatic vegetation, McFarlane said. A square-shaped island was also added to optimize wind fetch reduction.

While there were some compromises in the selection of the final design – some habitat benefits were reduced with a smaller design in order to meet cost requirements – the overall project used extensive data to tweak the placement and shape of the islands to maximize wind fetch reduction and habitat benefits.

The material that will be used for the project will most likely come from the Lower Pool 2 Temporary Placement Sites at Pine Bend, Upper Boulanger or Lower Boulanger, where the majority of the sediment in the area comes from. Typically, the upper pools of the Mississippi River do not generate as much sediment as the lower pools.

Project Future

The public comment period on the feasibility study concluded in April. McFarlane and Campbell did not anticipate any substantial changes to the report. From there, the report goes to the Mississippi Valley Division office for final approval and sign off on the project. The final approval should happen in June.

The cost-share agreement will also need to be finalized with the sponsor before the project moves forward. Local funding from Ramsey County Parks still needs to be established. Campbell said the county is pursuing a few different state grant options. Following the final approval of the report and an executed cost-share agreement with the sponsor, design would take about a year, and construction on the project would be slated for fall 2019 or summer of 2020.