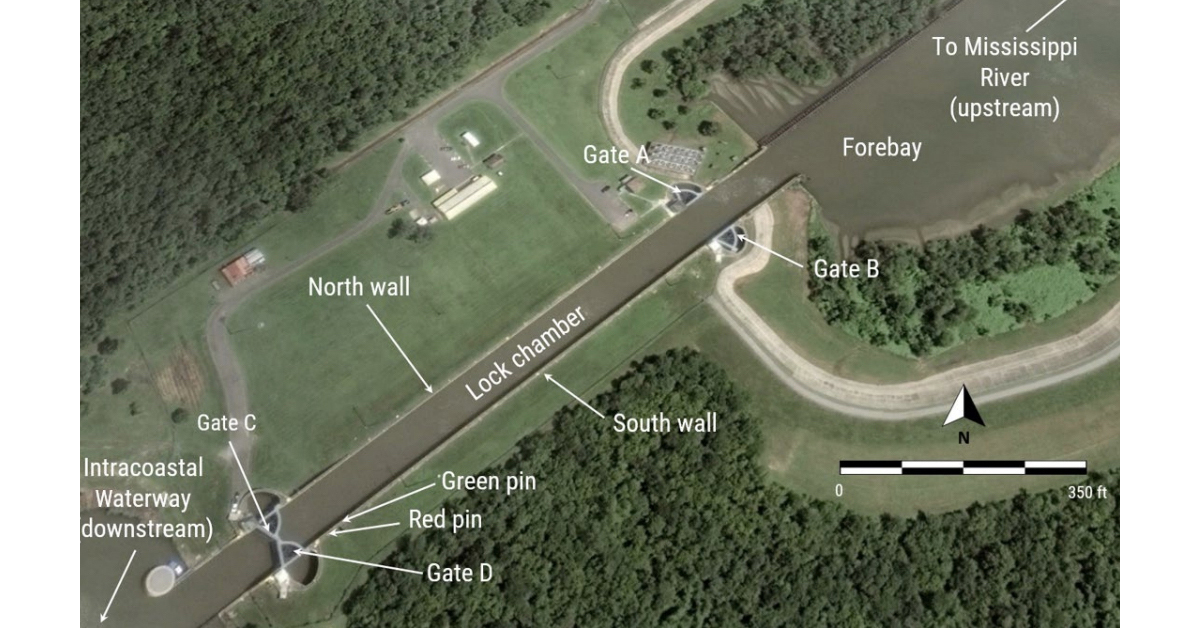

A National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report dated January 14 determined the probable cause of a July 4, 2023, allision between the mv. Kitty’s lead barge and Algiers Lock, located at Lower Mississippi Mile 88.4, to be surging waters from passing ships. The allision caused $2 million in damage to the lock’s canal-end sector gate. Algiers Lock is the main connection point between the Mississippi River and the western reach of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW).

About 6:08 p.m., the mv. Kitty, owned and operated by Enterprise Marine Services LLC, was pushing two of the company’s loaded tank barges through Algiers Lock when the lead barge struck one of the lock gates. No injuries and no pollution were reported. Damage to the barge was negligible, according to the NTSB, but lock gate D sustained an approximately 16- to 20-foot gash and a large inset in the steel plating. Steel support members were also damaged, and the gate walkway was bent.

The NTSB said three deep-draft vessels passing in quick succession, combined with extreme low water on the Mississippi River, caused a water surge in the lock that led to the allision.

The Corps of Engineers reported the cost of lock gate repairs was $2,082,677. The lock was reopened about 3.5 hours after the strike and remained functional, thanks in part to low water conditions at the time keeping the water level on both the river and GIWW below the puncture in the gate.

Investigation Into Allision

The captain of the mv. Kitty reported that, as the tow entered the lock, he looked at the automatic vessel identification information displayed on his vessel’s electronic chart system and saw the 587-foot-long tanker Garden State and, about 1.5 miles astern, the 820-foot-long tanker SKS Darent. Both were transiting southbound on the Mississippi River toward the lock forebay entrance.

At about 5:52 p.m., the Garden State began to pass the mouth of the forebay at 15.5 mph, according to the NTSB. The vessel was about 1,065 yards away from the open lock gates.

About 5:57 p.m., the stern of the Kitty was past the open lock gates in the chamber, moving at 0.7 mph as the captain maneuvered the tow closer to the south wall. A minute later, the SKS Darent passed the lock forebay at 15.9 mph. Another minute later the Kitty tow, fully within the lock chamber, had stopped moving. Using a handheld radio, the deckhand was calling the distance for the captain to come ahead to the red pin, 38 feet from the closed canal-end lock gates, as indicated by the day lock operator. This was because the mv. Pamela Ann, transiting lightboat, was also to enter the lock aft of the Kitty.

“The captain tried to ease the tow further ahead, but the Kitty tow began to move aft,” according to the NTSB Report. The captain saw water “coming out” of the lock and that the water was “pulling” the Kitty tow aft out of the lock chamber toward the Mississippi River.

At 6 p.m., the Kitty tow was moving 0.6 mph astern, and the captain came ahead slow on all engines to counteract the tow’s movement, the NTSB said. The captain stated over the Algiers Lock radio frequency that passing ships were “sucking the water out at Algiers.”

“At 1801 [6:01 p.m.], the Kitty tow was still moving astern, now at 2 mph, despite engines being slow ahead,” the NTSB reported.

At 6:02 p.m., the northbound 580-foot-long loaded bulk carrier Yasa Tulip passed the forebay at 11 mph at about 1,115 yards from the open lock gates.

“About 1804 [6:04 p.m.], the Kitty stopped moving astern, and the vessel was outside of the open gates, with the stern of EMS 383 (the aft barge) abeam of the open [river-end] lock gates. The captain put the engines in reverse in anticipation of water surging back into the lock; he estimated the lock had dropped about 3 to 4 feet. Less than a minute later, the Kitty tow started to advance ahead even though the engines were in reverse.”

By 6:06 p.m., the kitty tow was advancing ahead at 0.7 mph and increasing in speed.

“The captain moved propulsion astern on all engines to arrest the increase in speed,” according to the NTSB report. “Seeing that the tow was still advancing ahead, the captain moved all main engine propulsion levers to full astern, but there was no effect on the tow’s advance. He instructed the steersman to look at the wheel (propeller) wash, and the steersman confirmed that the engines were in reverse. At the head of the tow, the deckhand placed a line on a red pin once it was within reach and tied it off, but the line broke as the tow continued moving ahead. The deckhand placed another line on the pin, and that line broke as well. The deckhand told the captain via radio that the Kitty was ‘coming in hot.’”

Over the radio, the lock hand announced that the tow was approaching too fast and told the captain to slow down.

The captain replied, “Algiers, I’m backing on everything. The [expletive] water’s coming back in from the [expletive] ships. I can’t get it to stop. I got everything hooked up.”

At the bow of the lead barge, the deckhand saw that the tow was going to hit the closed lock gate and walked aft on the barge to safety.

At 6:08, moving at 1.4 mph, the port bow of barge EMS 317 struck gate D, the closed gate on the south side of the lock. The Pamela Ann, which was aft of the Kitty and waiting in the forebay, also surged forward. Its captain “backed down hard” to slow its forward motion.

After EMS 317 struck the lock gate, the captain of the Kitty backed the tow out into the forebay and tied up outside of the gates.

Analysis Of Cause

The NTSB report noted that the day lock operator told investigators the Kitty tow initially entered the lock at a normal speed. The tankerman, located on the aft barge during the contact, said the water in the lock chamber dropped about 5 to 6 feet based on the water marks on the lock wall. He said in the past when he had seen water surge into the lock, the water would normally drop about a foot and then go back up. The tankerman stated he had never seen the water surge as severely as it did while the Kitty tow was in the lock that day. The deckhand who had been on the lead barge estimated that the water in the lock chamber dropped at least 6 feet during the same period.

The NTSB conducted a video study of water level variations in Algiers Lock based on video footage from the Kitty and determined the water varied by at least 3.4 feet and possibly more, noting that only four water level estimations were possible during the analyzed 187.2 seconds of video.

The NTSB noted that the Corps of Engineers had no previous records related to vessels or barges striking the gates at Algiers Lock and that lock staff said they had never witnessed or heard of a similar occurrence. However, the night lock operator, who had worked at the lock for 13 years, said he “had seen vessels be displaced by interrupted water flow from the river side,” although no incidents as severe as the Kitty tow hitting the lock gate. That operator noted had he never seen the river at such a low level as it was during the casualty. The day lock operator said other boat captains had told him by radio that their vessels would surge when ships passed the lock.

NTSB Determinations

The captain of the Kitty held a master of towing credential since 2007 and worked in the towing industry since 1998. He estimated he had piloted vessels through Algiers Lock more than 100 times without issue. The captain and on-watch crew of the Kitty were tested for alcohol and other drugs, and the results were negative.

The NTSB said video footage captured no evidence of an erroneous or inadvertent movement of a steering or propulsion control lever. The NTSB also noted that there were no speed restrictions for deep-draft vehicles transiting the Mississippi River near Algiers Lock and the forebay. There were also no special procedures or considerations for low-water conditions in Algiers Lock, although gage heights were reported to be “extremely low” near the lock entrance from the river. At the time of the allision, the Coast Guard had issued a safety advisory of the low-water conditions and the need for river pilots to maintain safe speeds when transiting in the vicinity of docks, fleeting areas and other vessels to minimize wake.

“Wakes from ships can travel for miles, and their waves can be hazardous to other vessels and infrastructure along shoreline,” the NTSB said.

Additionally, effects of water displacement from the wake of deep-draft vessels can increase “when the water pushes into and recedes from narrow and/or smaller water bodies, such as shallow areas and lock chambers,” the NTSB said.

“The captain of the Kitty described that the tow was pulled out of the lock, which is consistent with the movement of receding water. Following that, the tow was pushed back into the lock chamber, consistent with rising water,” the NTSB report said. “Neither of these conditions occurred when there were no ships transiting the river nearby. Thus, it is likely that wake effects from deep-draft ships transiting the Mississippi River adjacent to the Algiers Lock forebay during extremely low water conditions moved water in and out of the forebay and lock chamber, causing the vessels in the areas to surge.”

The New Orleans Engineer District closed Algiers Lock for repairs on October 2, 2023, with the district’s skilled labor unit repairing the damaged sector gate. The lock reopened to navigation 58 days later, two days ahead of schedule.