In the last column, we began looking at a letter written by noted historian and author Capt. Frederick Way Jr. to M.C. Dupree, marine superintendent of Ashland Oil & Refining Company (AO&R). The letter explained how and why the towboat Ashland had been unaccounted for over several days during December 1942 and January 1943.

The Ashland, built by Calumet in Chicago in 1941, was 145 by 31 feet and had 1,610 hp. from a pair of Fairbanks-Morse model 37E direct reversing diesels.

The Ashland departed Kenova, W.Va., on December 27, 1942, upbound on the Ohio River with six loads of finished petroleum for Pittsburgh. At that time, there were no on-board communication systems, and the only way to contact the office was to find a telephone ashore. Last week’s column left off with Capt. Way writing, in his entertaining fashion, that the boat and tow tied off because of foggy conditions on the evening of December 28 at Mason City, W.Va., about Mile 250, opposite Pomroy, Ohio. Capt. Way went ashore and phoned ahead to check river conditions and was told that a 1-foot rise was predicted out of both the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers.

His letter continued:

December 29 started in just as the 28th left off—fog and rain. This combination kept up all morning. At noon or just after, it cleared up a little, and we started moving upstream again. Henry Dixon was on watch, and he kept plugging along till supper time. [Note: Capt. Henry Dixon would later be the pilot on the AO&R towboat Tri-State in November 1946 when it made the first trip equipped with a radar.] I came on watch to discover that the river had taken on a new look—fodder running. Now, when finely divided fodder starts running in any man’s river, it means but one thing, a rapid rise. I don’t know why this is so, but it is so, and you can count on it and never be fooled about it.

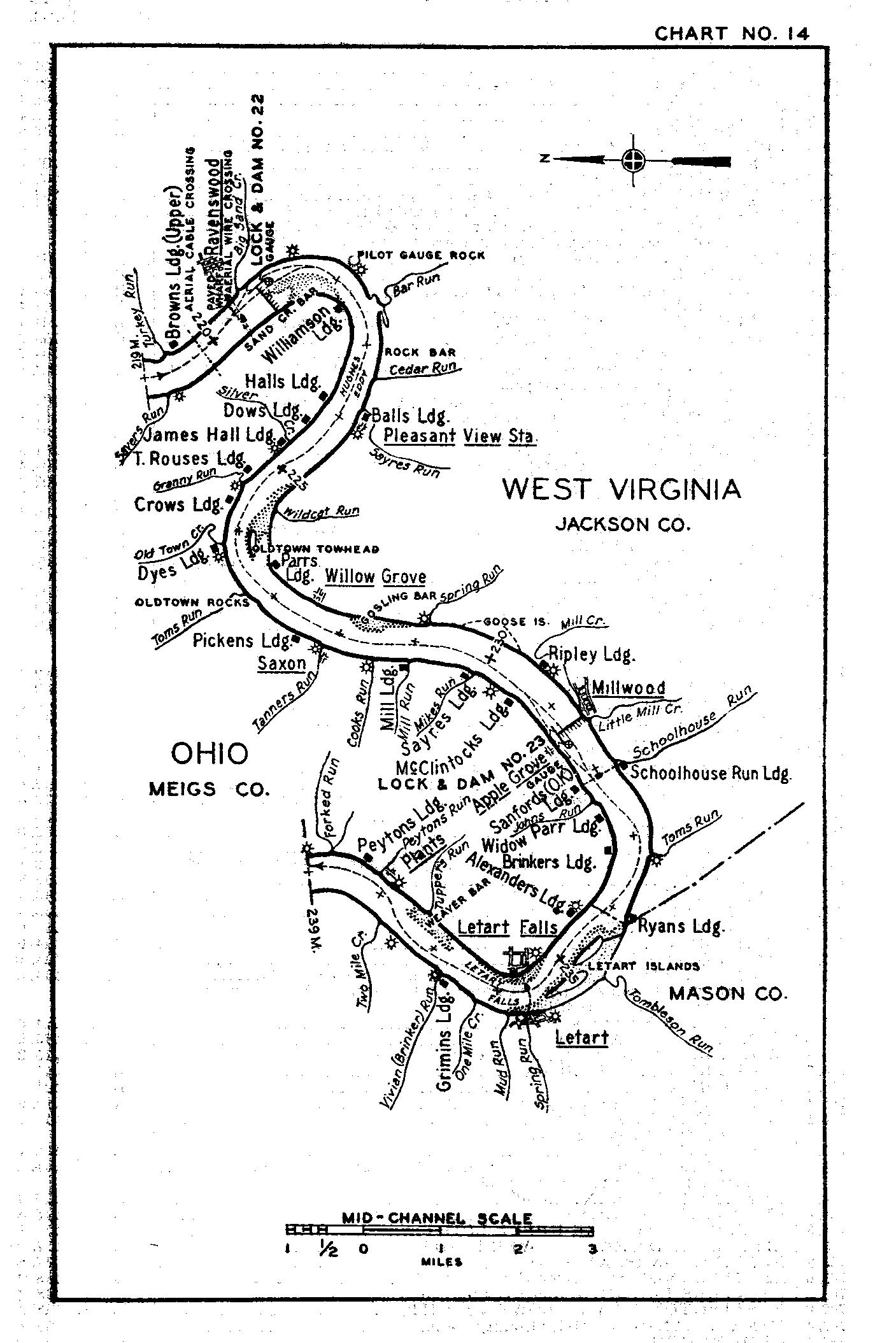

I smelled a flood coming; just sniffed up a rain spout and was convinced of it—all the earmarks were there. We had gone through a zero spell, and it was obvious that all the ground from headwaters to Kentucky was frozen solid; we had been having rain for two whole days, the wind was from the east (which is good for neither man nor beast), and I commenced thinking about all the big sycamore trees in the country which might make the best tying up place and decided on a location along the Ohio shore below Letart Falls, Ohio, just above the mouth of Tupper’s Creek and abreast of a house wherein lives a family named Sayre. [Note: This spot is just above present-day Racine Dam, Mile 237.5.] We landed at this haven at 7 p.m. and set out a gauge pole. One hour later all suspicions were confirmed—the river was rising 10 inches an hour.

Well, by nine o’clock the morning of December 30, the river had shot up nine feet higher than when we tied up at seven the night before, and still was going up six inches an hour. We cut the boat loose from the tow and went down to the peaceable hamlet of Racine, Ohio, and did some telephoning. The lockmaster at Lock 23 told us that he had 38 feet on his gauge and was expecting 55 feet. Well, 51 feet puts water up in the stores at Racine, and 66 feet puts the B&O [Railroad] out of commission and stops all the river roads. We went back to the fleet and made sure of all of our lines and led good “come back” lines to the bases and waited. While the rain continued most of the day.

The B&O gave up the ghost at 10 that morning—last train went up. We fiddled with the radio all morning trying to get news, and all we got was music. Charley Mays came in about noon with a big, long-jointed fellow whom he introduced as F.R. Clement—and he turned out to be the superintendent of the Union Sand & Gravel Company, Huntington. They had a big sand fleet tied under the West Virginia point about a mile below us, and now the river had flooded in behind the trees where they were and was coming in through the bottoms from behind.

Drift was piling down on them—and would we please come down and move them to a safe place. (You can’t tie up for a flood under any point where there are trees—you’ve got to find a point where the bank is above flood level—if you want to sleep at night). So we raised steam and went down there and moved the whole shebang, which consisted of the usual collection of junk in a sand digger outfit.

First, we towed five empty flats across the river and up under where we were lying, then we brought up a loaded sand flat, then we came up a third time with the digger, four more flats, a partly loaded barge, a derrick and a work flat. The rescue was accomplished, as dime novels would put it, in the “nick of time” for a house sailed by just as we left, and had we been a little later it might have lodged in the head of the digger fleet. More wonderful, this house was built of corrugated iron—the only iron house I ever saw floating down the river. (I saw a brick house go down in 1913.)

Mr. Clement was very grateful for the “lift,” and we went back to our fleet and noticed the river was still booming up, and although the rain had stopped, and the air was some colder, it now looked like it might snow. Thus ended the last day of the year A.D. 1942, December 31.

The next column will continue this narrative of towboating as it was 82 years ago.