In the ever-evolving landscape of commodity supply chains, the dual threats of drought and flooding present significant challenges. Over the past month, I have spoken at several industry events and meetings, discussing commodity supply chains. At the National Waterways Conference (NWC) in New Orleans for example, I presented “Too Little, Too Much: Navigating Drought and Flooding Challenges.” I focused on the national perspective, emphasizing the critical need for a resilient and adaptable supply chain framework.

The 4-Rs Framework

For commodity supply chains, especially for agriculture, I have prepared a 4-Rs framework of Reliable, Resilient, Resourceful and Redundant, in maintaining a robust commodity supply chain. This framework is not just a theoretical construct but a practical guide to navigating the complexities of modern logistics.

• Reliable: An established and integrated network is crucial. Reliability ensures that the supply chain can withstand disruptions and continue to function effectively. For agriculture, it has deep tentacles from where crops are grown.

• Resilient: Multiple options from farm to market provide the flexibility needed to adapt to changing conditions. Resilience is about having contingency plans and alternative routes. Agriculture in the United States enjoys multiple outlets and routes for domestic consumption while sending to the global marketplace.

• Resourceful: High volume, throughput, and efficiency are key. Being resourceful means maximizing the use of available resources to maintain flow and reduce bottlenecks. U.S. agriculture, especially crops such as corn, soybeans and wheat, have a harvest system to rapidly move from field into the supply chain given the storage and handling capabilities of the grain industry. And it is not just storing and holding crops but allowing crops to flow through the system from farm to barge loading facilities along the Mississippi River & Tributaries to export position in the Center Gulf, for example.

• Redundant: A plug-and-participate system allows for redundancy, ensuring that if one part of the supply chain fails or is disrupted, others can take over. It is not an either/or where U.S. crop production is only for food or only for fuel. Rather, it is a both/and where farm productivity allows crops to be transformed domestically and be sent globally to feed, fuel and provide the fiber of economies around the world. Crops are a matter of national security and having redundant systems allows users to plug-and-participate.

Waterway Challenges

In the NWC presentation I highlighted several waterways that exemplify the challenges faced by the commodity supply chain:

• Mississippi River. Known for its critical role in transporting agricultural products, the Mississippi River’s fluctuating water levels can significantly impact logistics.

• Rhine River. Europe’s key waterway, the Rhine, faces similar challenges, with low water levels disrupting transport and increasing costs.

• Panama Canal. A vital link in global trade, the Panama Canal’s water levels directly affect vessel loadings and dry bulk freight rates.

• Madeira and Amazon Rivers. These South American rivers are crucial for regional trade but are also susceptible to the impacts of drought and flooding.

Economic Impacts

Disruptions in the supply chain lead to a cascade of economic effects. Reduced transport capacity necessitates more capacity to move the same volume, which in turn leads to higher freight rates. These increased costs are often passed on to consumers, while farmers absorb the impact through weakened basis, and end up “paying the freight.” Local and regional economies suffer from lost economic activity, highlighting the interconnected nature of these challenges.

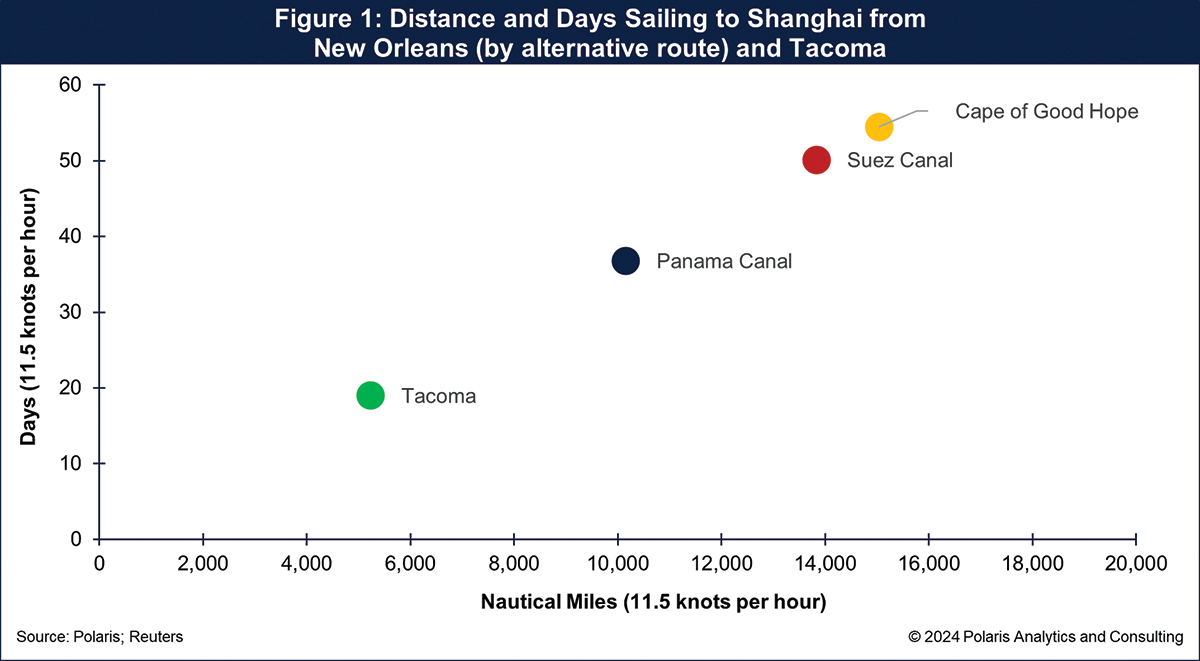

Farmers and grain handlers in the U.S. have strategic considerations for routing grains, soybeans and associated products to the world. As an example, consider sending crop to China through New Orleans on the Lower Mississippi River, the Panama Canal, the Suez Canal and the Cape of Good Hope. Each present unique challenges and opportunities. There are options through the Pacific Northwest too. The choice of route can significantly impact on costs and delivery times, making strategic planning essential.

A look at the number of days for a vessel to sail to China from the U.S. using different routes is show in Figure 1.

Water Levels

Water levels play a pivotal role in commodity flows. As highlighted, commodities flow like water, taking the path of least resistance. This analogy underscores the importance of maintaining optimal water levels in key waterways to ensure smooth and efficient transport. Low water levels can lead to reduced vessel loadings, higher freight rates and, ultimately, increased costs for consumers.

As an example, the Panama Canal endured a severe drought throughout 2023 into mid-2024. The Panama Canal Authority limited vessel transits and draft capabilities through the Neopanamax locks.

They could have limited draft through the Panamax locks too but held off doing so. Had they instituted draft restrictions such as they had in the past, it could have become more expensive transiting the locks.

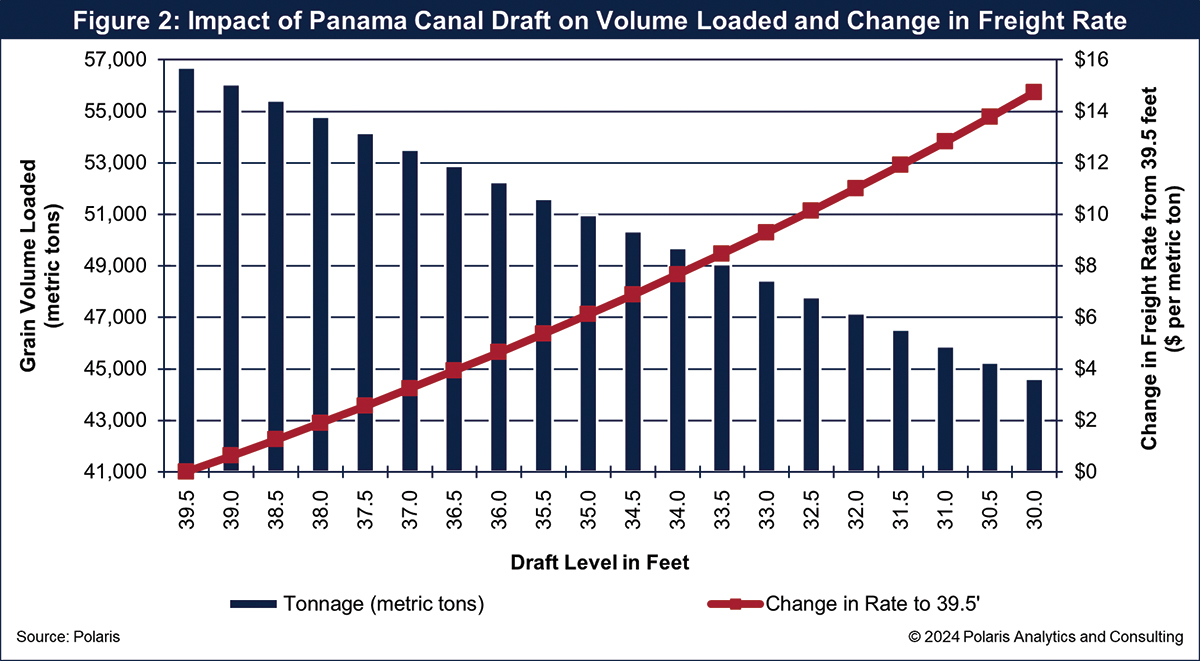

In Figure 2 there is an example of restricting vessel draft in 6-inch increments from the maximum 39.5 feet through the Panamax locks. Each 6-inch draft restriction is the equivalent to 636 fewer commodity tons loaded on a vessel.

With fewer tons loaded, the freight rate increases 1 percent or 63 cents per metric ton for each 6-inch draft restriction. However, the impact is not a linear response, rather a curvilinear in function where ensuing draft restrictions lead to freight rate costs that increase at a faster pace.

The reality is that it would not take too many draft restrictions before shippers look for alternative routes or markets to source their grain, soybean or product needs. Last year’s drought at the Panama Canal did see shippers send vessels through the Suez Canal or around the Cape of Good Hope, while using the Pacific Northwest route to Asia. And Brazil benefited too with lower freight costs.

A Call to Action

For stakeholders in the commodity supply chain there is a call to action. While the economic example used in the NWC presentation was an impact through the Panama Canal, the same exercise is true of barges using the Mississippi Rive & Tributaries or ocean-going vessels being loaded on the Lower Mississippi River or Columbia River in the PNW.

Maintaining a reliable, resilient, resourceful and redundant supply chain is not just a goal but a necessity. Water levels must be monitored and managed to prevent disruptions, and strategic planning must keep the 4-Rs in perspective.

The challenges of drought and flooding are not going away. However, with a robust framework and strategic planning, the commodity supply chain can navigate these challenges and continue to support local and regional economies. As I pointed out, “Water levels make or break commodity flows, and commodities flow like water, taking the path of least resistance.”