Food and farm products (such as grain and soybeans) are move by barge in substantial volumes on the inland rivers. In 2022 (the last year available for official data through the Army Corps of Engineers), they totaled 84.6 million short tons, down 9.4 million short tons or 10 percent from 2021. On a ton-mile basis, food and farm products contributed 80.9 billion ton-miles (moving one ton of cargo one mile) during 2022, which was a drop of 7.9 billion or 8.9 percent from 2021.

Compared to other commodities moved on the inland system, food and farm products represent 19 percent of the tons and 36 percent of the ton-miles. For the covered barge fleet, food and farm products are significant, representing 60 percent of the tons and 71 percent of the ton-miles. Most of the food and farm product volume is moved to export positions in the U.S. Center Gulf region.

As the calendar turned to September, a new crop marketing year started for corn, sorghum and soybeans, and with it the promise, or hope, of improved crop export potential. The small grains marketing year for barley, oats and wheat started June 1.

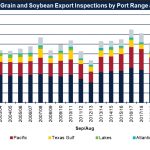

U.S. Grain & Soybean Export Forecast

In the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates report, released September 12, new crop exports for the 2024-2025 marketing year are forecast to total 136.3 million metric tons (5.175 billion bushels). If realized, that would be 7.5 million metric tons or 5.8 percent above the 2023-2024 marketing year. It would also be the largest export program since the record of 27 million metric tons set in 2020-2021 and the fifth largest program in U.S. history.

Leading the way higher is the soybean crop, forecast to total 50.3 million metric tons (1.850 billion bushels) during 2024-2025, which would be 4.1 million tons or 8.8 percent higher than the previous year. Soybean exports set a record in 2020-2021 at 61.7 million metric tons.

Corn exports are forecast to total 58.4 million metric tons (2.3 billion bushels) during 2024-2025, which would be 1.3 million tons or 2.2 percent above last year’s program.

Wheat exports are forecast to be 22.5 million metric tons (825 million bushels) during 2024-2025, 3.2 million metric tons or 16.7 percent higher than last year.

Sorghum exports are expected to be laggard, totaling 4.9 million metric tons (195 million bushels), which would be a drop of 1 million tons or 17 percent from the previous year.

Grain and soybean exports by crop, and overall are shown in Figure 1.

From The Mississippi River & Tributaries To The World

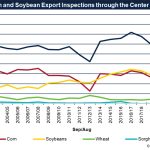

The Center Gulf dominates the U.S. grain and soybean export market by port range (e.g., Center Gulf that includes the Mississippi River, Texas Gulf, Pacific Northwest including the Columbia River and Puget Sound export elevators). Export elevators in the Center Gulf handle about one-half of all grain and soybean export volumes. By crop the Center Gulf handles 58.1 percent of U.S. corn and soybean exports each and 16.9 percent of wheat exports.

Grain and soybean exports by port range are shown in Figure 2.

Over the past decade the export elevators in the Center Gulf have handled between 60 million and 70 million metric tons of grain and soybean exports. Exports of corn and soybeans represent the largest volumes of exports, hovering near 30 million metric tons each.

Grain and soybean exports through the Center Gulf are shown in Figure 3.

Like a giant funnel, the Mississippi River & Tributaries system is an important artery for farmers to see their grain and soybeans enter the global market and for buyers around the world to assure food security and meet fuel needs in their countries. Because of the investment by commercial and private companies, the federal government, state and local authorities, the Mississippi River & Tributaries system allows grains and soybeans to be delivered in a safe, efficient, sustainable and competitive manner.

Barges loaded with grain and soybeans from across the inland river system deliver 98 percent of the grains and soybeans exported through grain elevators in the Center Gulf between Baton Rouge and Myrtle Grove, La. Because of the safe and efficient navigation system and investments made over decades, the Center Gulf elevator network sends grains and soybeans to dozens of global markets that are dependent on U.S. crops for their food and fuel needs.

A Resilient System With Challenges

The Mississippi River & Tributaries system flows through the heart of the Corn Belt and is the vein of the grain and soybean export supply chain. Despite the numerous challenges thrown at it, the system keeps flowing and the goods are delivered to market.

Now in a third year of low water, draft restrictions have limited the amount of tonnage loaded on a barge or ocean-going vessel. As an example, each 6-inch draft restriction reduces loadings by about 106 metric tons or 116 short tons. Barge tow sizes are limited, speeds are reduced and hours restricted on movement through certain sections, further exacerbating the flow of grain and soybeans to export positions.

With successive draft restrictions, the transport cost is spread over fewer tons loaded, making the rate more expensive on a per unit basis. In fact, freight rates rise at an increasing level because there is not enough equipment to meet the demand for displaced products.

This year’s low water in Memphis, Tenn., for example, started in mid-August, hitting the third lowest stage level on record this past week, for the third consecutive year. Based on Hurricane Helene’s path through Florida’s Big Bend, the storm will move inland over the Tennessee and Ohio river valleys. If Helene does take that path, substantial volumes of rain will be dumped over those river basins. Conceivably that rain could recharge those river basins and then be available to bring relief downriver in Memphis, for example.

Meanwhile, low water is not just a problem in the United States. In South America, the Madeira River is at historic lows due to persistent hot, dry conditions in central and northern Brazil. The low water is impacting water levels on the Amazon River, and the dryness is impacting the Paraná River to the south as well. Given the conditions in South America, barge loadings are all but dried up, and draft restrictions have severely impacted ocean-going vessel loadings on the Paraná. Corn exports are being hampered as well.

The Mississippi River & Tributaries system benefits from close collaboration between industry, the Army Corps of Engineers and Coast Guard to communicate trouble spots, directing dredge equipment to maintain the safest possible draft while working to keep the river from being shut down for an extended period. Such efforts need to be applauded, celebrated and communicated so that buyers around the world can be assured their grain and soybeans can be sourced from the U.S. despite low water conditions.

In the meantime, the river systems in South America do not have the same collaboration or resources to dredge and keep the rivers operational.

U.S. grain and soybean exports are expected to rebound during 2024-2025. The Mississippi River & Tributaries system is an important artery serving farmers and exporters and feeding and fueling the world. As conditions worsen in South America, the U.S. is poised to see increased export volumes, making the Mississippi River and Center Gulf even more important to the world.