This writer has never believed in “luck,” per se, but does believe that the subject vessel of this column was most unfortunate at times. It was the subject of feature news stories in The Waterways Journal in 1937 and again in 1939. It also has a loose association with the Del Commune that we looked at in the last column.

The Howard Shipyard & Dock Company, Jeffersonville, Ind., was noted for the packets that the company built starting in 1834. It turned out its first towboat in 1877. In 1911, Howard built a towboat for the Roane Iron Company with a reported cost of $18,500. It was named H.S. Chamberlain (Way’s Steam Towboat Directory T1024) and was a wood hull steam sternwheeler. That hull was 140 by 30 feet, and the engines were 16’s, 6-foot stroke. Roane operated the boat on the Tennessee River.

Way’s says that Capt. W.H. Phillips was master of the Chamberlain, and that it was the first privately owned vessel to pass through the two locks at the Wilson Locks and Dam when they opened in 1926. Also in 1926, the original wood hull was replaced with one built of steel. Dimensions then were 135.5 by 30 feet.

It was sold to steamboat broker John F. Klein in 1929; he in turn soon sold it to Northwestern Terminals Company, Evansville, Ind., and it was renamed Weber (T2623).

This new owner had a plan to revive the coal business on the Green River and purchased several boats and barges. In June 1929, the Weber made an initial trip with coal from the Green that was delivered to Memphis. Unfortunately, probably because of the Great Depression, the boat was sold at a U.S. Marshals sale in February 1931 for $7,100 to James P. Goodrich, a former governor of Indiana. Utilizing the services of broker John F. Klein, the boat was again sold in March of 1931 to E.V. Rawn of the Ohio River Dredging Company, Huntington, W.Va.

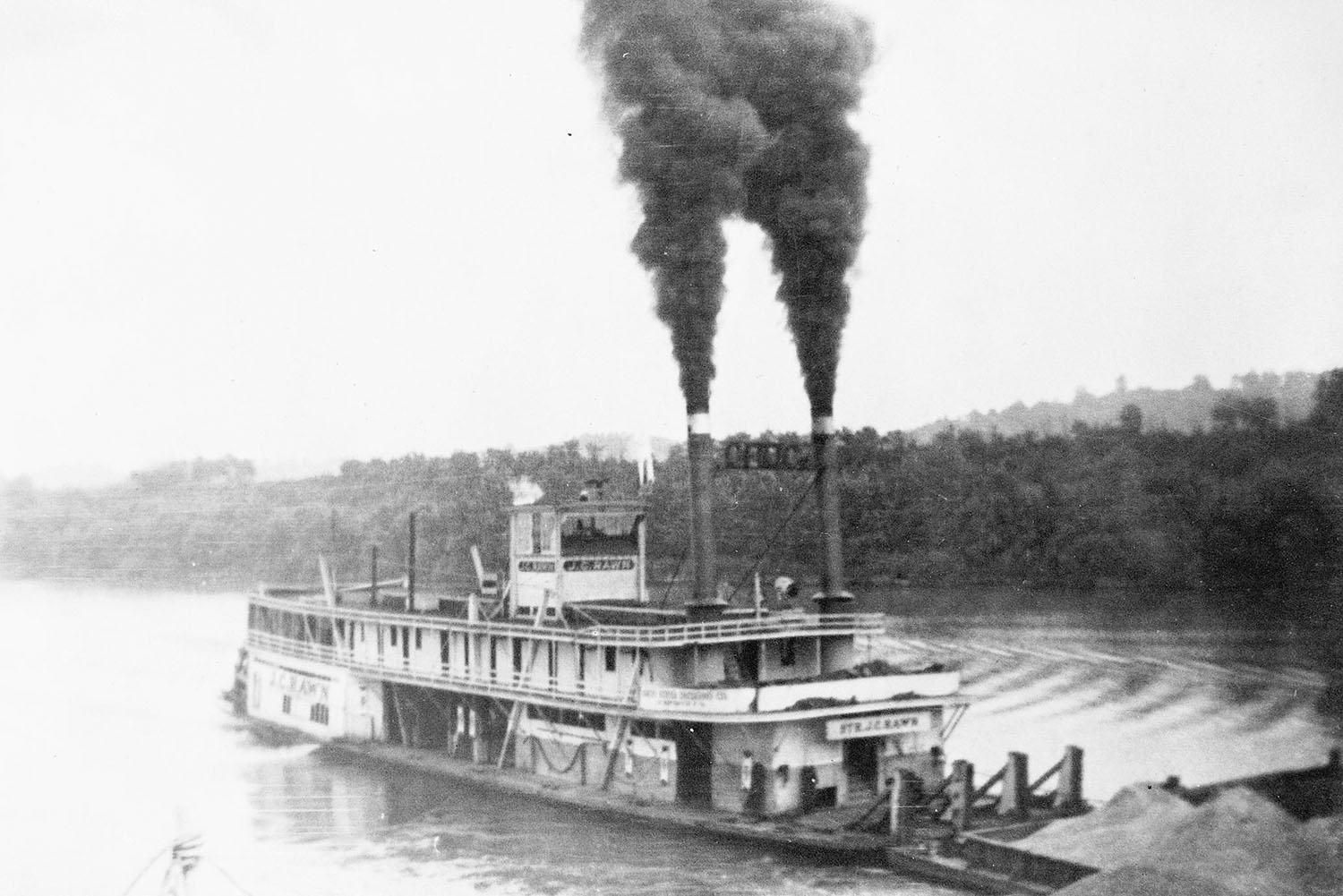

Way’s indicates that the sale price of the boat “was said to be $40,000.” The name was changed to J.C. Rawn, and Way’s lists its first master for OR Dredging as Capt. Jesse Johnson, with Capt. Raymond Young as pilot. OR Dredging used the boat to tow sand and gravel and to do job towing.

In the mid-1930s, it was often towing coal from mines at Harewood, W.Va., to the Semet-Solvay coke plant at Ashland, Ky.

The great Ohio River flood of 1937 began on January 5, 1937, in the upper reaches of the river, and the rise continued as 6 to 12 inches of rain fell, in places on top of a heavy snow pack. On January 26, the river crested at 79.9 feet at Cincinnati, a record that stands today. Throughout the valley, some 385 people died, 1 million were left homeless, and property losses were estimated at $500 million ($11 billion today). Finally, on February 5, the Ohio began a slow fall to below flood stages.

On the morning of February 13, 1937, the “unfortunate” J.C. Rawn was upbound on the still swollen river with four empty barges, headed for the Harewood mines. In the February 20, 1937, issue of the WJ was a small story that said at 5:45 a.m. on the 13th, the Rawn was running close to the West Virginia shore and opposite the lower end of Gallipolis Island when it ran aground. Capt. Harry Wright was the pilot on watch, and his brother, Capt. McKinley “Mack” Wright, was the master and preparing to come on watch when the incident happened. After blowing distress whistles “that awoke everyone in Gallipolis (Ohio)” the steamer Fairplay (Way’s T0793; WJ May 8, 2023) and the steamer Iroquois (T1209) of the U.S. Engineers came to the aid of the Rawn and after “valiant efforts” failed to pull it back into deep water.

The Gallipolis Gossip column, authored by Frank Sibley in the March 6 issue, revealed that the Rawn was now “high and dry.” Sibley said that the owners were making the best of the situation, and that the hull was being painted and the boilers were being repaired. He also listed numerous other boats that had stranded, exploded, burned or sunk near the same spot, saying that Gallipolis Island might be called a “hoo-doo” to rivermen.

The April 10, 1937, issue of the WJ had a piece about the Rawn still being “aground in a cornfield,” and that E.V. Rawn of the OR Dredging Company, who had a degree as a mining engineer, had devised a plan to refloat the boat, which was sitting some 20 feet from the water’s edge. The issue of April 24 carried a large spread, including photos detailing how the boat was refloated, authored by Rawn. His method had involved digging a series of ponds and floating the boat back into each one.

When the boat was in the second such pond, an earthen dike was constructed behind it, and a floating crane dug a channel to the river. The gates of the Gallipolis Dam (then quite new) were “lowered sufficiently to back water to 6 feet above normal pool.” The dike was then dug out, and the Rawn was pulled out about 125 feet by a line from the floating crane before traversing the final 300 feet “under its own steam into the Ohio River.” The plan had been approved by Neare, Gibbs & Company, representing the insurers, and the Neare, Gibbs representative on scene, Capt. W.C. Lepper. Most of the work had been performed by equipment and employees of the Ohio River Dredging Company, at a cost of less than $4,000 ($88,000 today).

Within two hours of being freed, the J.C. Rawn faced up to a tow and was once again headed upstream after a two-month hiatus.

The next column will detail the next and final misfortune suffered by the J.C. Rawn, and look at the connection to the Del Commune.

Caption for top photo: Str. J.C. Rawn in service for the Ohio River Dredging Company. (Author’s collection)

Capt. David Smith can be contacted at davidsmith1955obc@gmail.com.