Almost a month has passed since a large portion of the upper miter sill at Demopolis Lock broke off and fell into the chamber on January 16, and the plan for returning the lock to normal operations is taking shape.

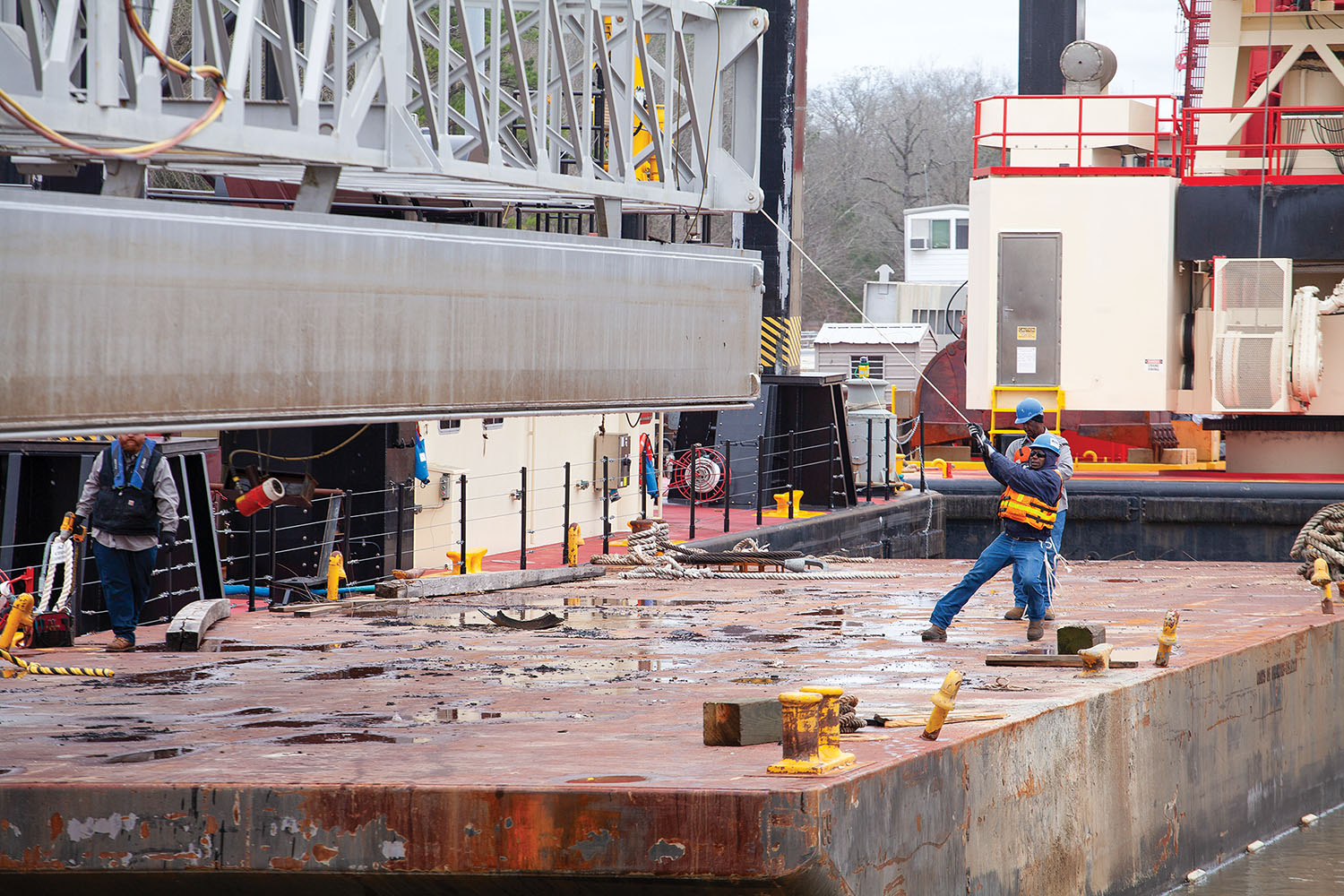

The Mobile Engineer District’s maintenance fleet, including the mvs. Tenn-Tom, Lawson and Constitution and their associated crane and deck barges, arrived to the lock from downriver on February 2. Corps leaders are keeping the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Project’s old crane barge, the R. Davis, equipped with a Manitowac friction crane, below the lock. The Black Warrior-Tombigbee Project’s mv. Lawson and its floating plant, the Choctawhatchee, and the Tenn-Tom Project’s mv. Tenn-Tom and new crane barge, equipped with a Liebherr crawler crane, locked through February 5. Floating plant crew members then restacked the lock’s upper stoplogs to elevation 84 feet, which gives lock operators more control over chamber water levels in the face of upper pool fluctuations.

After assessing repair options, Mobile District engineers, in partnership with the U.S. Army Engineer Research & Development Center (ERDC) and the Corps’ Inland Navigation Design Center (INDC), have completed the plans and specifications for repairing the damaged miter sill.

The repair plan calls for both replacing the failed section of concrete and buttressing the entire upper miter sill to guard against another failure in the future. Anthony Perkins, operations project manager for the Black Warrior-Tombigbee Waterway Project, said Demopolis and Selden locks are unusual on the system in that their upper miter gates are framed vertically, which means the load from the upper pool is transferred directly to the sill.

“You’re continually loading it every lock cycle,” Perkins said.

With Demopolis Lock turning 70 this year, that wear and tear looks to have finally taken its toll. Buttressing the upper miter sill will result in shortening the total length of the chamber by 2 feet, but the lock will still offer a 602-foot chamber post-repair.

Because of the dynamics of the Tombigbee River, the lock’s lower stoplogs can only be stacked to an elevation of 40 feet. With the region in its traditional high-water season, those lower stoplogs are likely to be overtopped during the course of the repair work. Thus, the Corps has opted to repair the upper miter sill “in the wet.” Perkins said the Corps’ engineering team is finalizing the formula for pouring concrete in the wet within the chamber. The Mobile District’s operations and maintenance contractor, R&D Maintenance, will secure concrete from a Ready Mix USA batch plant located just upriver from the lock. The Corps expects to source about 2,000 cubic yards of concrete for the repair work.

No firm completion date has been given, but with individual concrete pours requiring seven days to cure, the district is sticking with a mid-May estimate for completing repairs and removing debris from the chamber.

The task of removing the upper stoplogs February 5 and restacking them the following day proved to be the first heavy-lift job for the Tenn-Tom Waterway’s new Liebherr crawler crane. Scott Beams, chief of the district’s technical support branch, who previously worked on the team that designed the new crane barge, said he is pleased with the floating plant’s performance so far.

“We feel like this new crane gives us a lot more capabilities and options,” Beams said.

In particular, the extra boom the new crane offers comes in handy on the Tenn-Tom’s and Black Warrior-Tombigbee’s high-lift locks and spillways, along with the ability to reach snags on the bank.

“Just having a big machine that can reach is a big help,” he said.

Meanwhile, operators, shippers and cargo owners are scrambling to move commodities and position assets following the unplanned closure, which effectively cuts off both the Tenn-Tom and Black Warrior-Tombigbee waterways from their shortest route to the Gulf of Mexico and the Port of Mobile. Chas Haun, executive vice president of Tuscaloosa, Ala.-based Parker Towing Company, said for now his company is sending boats up the Tenn-Tom Waterway and down the Tennessee and Ohio rivers to the Mississippi River. In New Orleans, those vessels then take the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway east toward Mobile, Ala.

“It adds about 1,600 miles to go around, so it’s going to limit our capacity for what we can do,” Haun said. “It adds greatly to the cost. When the lock went down, it went down without notice, and we already had barges loaded.”

Other modes of transportation lack the capacity needed to shift cargoes from the waterways during the closure. The far-reaching impact of the closure is still coming into focus, Haun said.

“The stockpiles are coming to a close,” he said. “I don’t think we’ve really seen the impact yet.”

Haun said he and other representatives from the maritime industry have been warning of the risk of this type of unplanned closure to Corps and political leaders in Washington, D.C., for quite some time.

“It’s vital they get the lock open as soon as possible before permanent damage is done to some of our shippers,” he said.

The Mobile District has the funds in hand needed to execute the repair work at the lock, with money redirected from the Black Warrior-Tombigbee Waterway Project’s planned new headquarters. District leaders said they hope to have those funds reimbursed through a future supplemental funding package.