The initial images from Algiers Lock in New Orleans back in the summer, following a July 4 allision, certainly made an impression. Around 6 p.m. that day, the lead barge of a tow entering Algiers Lock from the Mississippi River allided with the canal-end sector gates, denting the north-side sector gate and knocking a 10-foot-wide hole in the south-side gate’s steel skin and also damaging that gate’s structural steel frame.

After initial assessments, lock managers from the New Orleans Engineer District determined there was no damage to the gate’s ability to swing open and close, and the lock reopened to navigation the same night as the allision. Emergency repair work, dubbed the “Frankenstein patch”—coupled with drought conditions that kept the hole in the gate above the water line in both the Mississippi River and the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW)—allowed New Orleans District officials to keep the lock open to navigation while they applied for $6.4 million to dewater the canal-end gate bay and make permanent repairs.

That 60-day closure began October 2. Now, with the target reopening date of December 1 in sight, Corps officials say repairs have gone well, thanks to the district’s own skilled labor unit and to the river’s continued cooperation.

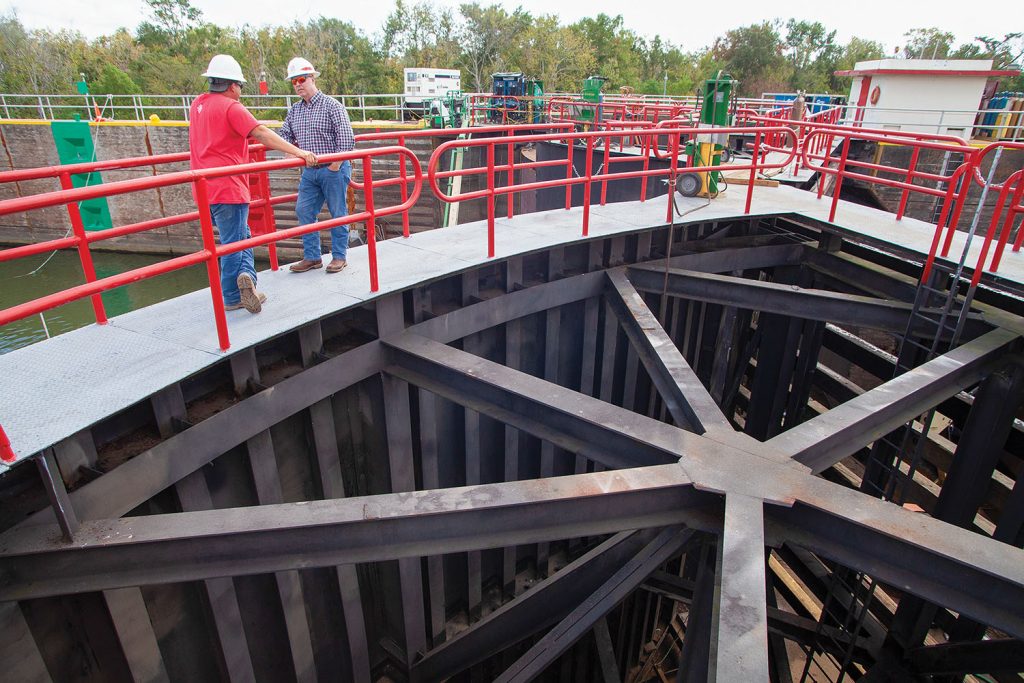

Vic Landry, operations project manager for the New Orleans District’s GIWW structures, said the fact that Algiers Lock has fan-shaped sector gates rather than barn-door-style miter gates was a real asset when the allision took place.

“Sector gates versus miter gates are so much more robust,” Landry said. “It’s a very simple design. All the weight sits on the pintle, and at the top is the hinge. It’s a simple design and very durable.”

Jesse Adams, the engineer-in-charge overseeing the district’s in-house labor team, praised his team, which has been working around the clock, first cleaning the chamber itself, then cutting out damaged steel and welding new steel in place.

“I’ve got to tell you, they’ve done a great job,” Adams said.

The crew of about 40 Corps employees has been working in two 12-hour shifts. During the daytime, welders cut out old steel and custom-fit new steel in place piece by piece. At night, crews finish welding the new steel into place.

“They’re out here at night with lights, arcing away,” Adams said.

Landry said having that skilled labor unit in house and available was crucial to being able to tackle such a big repair job on such short notice.

“We’ve got good people,” he said. “That’s the bottom line. And they know what to do.”

While the canal-end gate bay has been dewatered, the Corps team has also taken the opportunity to inspect both gates and do some preventative maintenance, like replacing zinc anodes that protect against corrosion and armoring the wings on the outer end of the gates. Landry said his team has been careful to account the preventative work separately from the allision repairs. Both Landry and Adams said, though, that the canal-end gate bay was last dewatered and serviced about a decade ago. The gates were nonetheless in overall good shape, not counting damage from the allision.

In addition, Algiers lockmaster David Smith has been doing his own carpentry work on the river-end operator’s office, essentially elevating the lock operator’s workstation and controls to make it easier to see transiting vessels.

“We’re saving the government money,” Smith said with a smile.

Landry said he recognizes how inconvenient the closure at Algiers is for operators that rely on the lock for traveling east and west on the GIWW. The closure at Algiers also coincided with daytime restrictions for ongoing work at Bayou Sorrel Lock on the Morgan City-Port Allen Alternate Route and the closure at Harvey Lock due to low water on the Mississippi River. Faced with the closure at Algiers, the Corps was able to craft protocols for opening Harvey Lock during daylight hours, Landry said.

“The alternate route is the primary route right now,” he said, “although that’s an extra 175 miles for tows.”

That’s why communication has been key throughout the planning and execution of repairs, Landry said, along with quick receipt of funding and the timing of the allision.

“All that gave industry time to plan around it,” he said. “Paul Dittman with GICA, Karl Gonzales with the Greater New Orleans Barge Fleeting Association, the Coast Guard—it was a great team effort by everyone.”

Dittman, president of the Gulf Intracoastal Canal Association, concurred.

“New Orleans District, U.S. Coast Guard Sector New Orleans and GICA initiated planning and developed protocols to best manage these disparate challenges well in advance of the closure of the Algiers Lock on October 2 and subsequently messaged critical navigation safety information to GICA membership on an almost daily basis,” Dittman said. “This effective, forward-leaning communication facilitated voyage planning and communication with customers and other impacted stakeholders to minimize supply chain impacts. The GICA-USACE-USCG relationship has been tempered over the years during major hurricane and other waterway emergency response operations, and the strength of these relationships was pivotal to effectively manage the potentially debilitating impacts created by the extended closure of the Algiers Lock.”

That team effort should result in traffic flows on the central GIWW back to normal in time for the holidays.

Caption for top photo: Crews working to repair a damaged sector gate at Algiers Lock, which was damaged in a July 4 allision. (Photos by Frank McCormack)