Just like last year, the Mississippi River is stuck on low, with much of the Mississippi and Ohio valleys experiencing extreme drought conditions. In the last 100 miles of the river, that means salt water moving up river from the Gulf of Mexico is again threatening the fresh water supply of communities along both banks of the river.

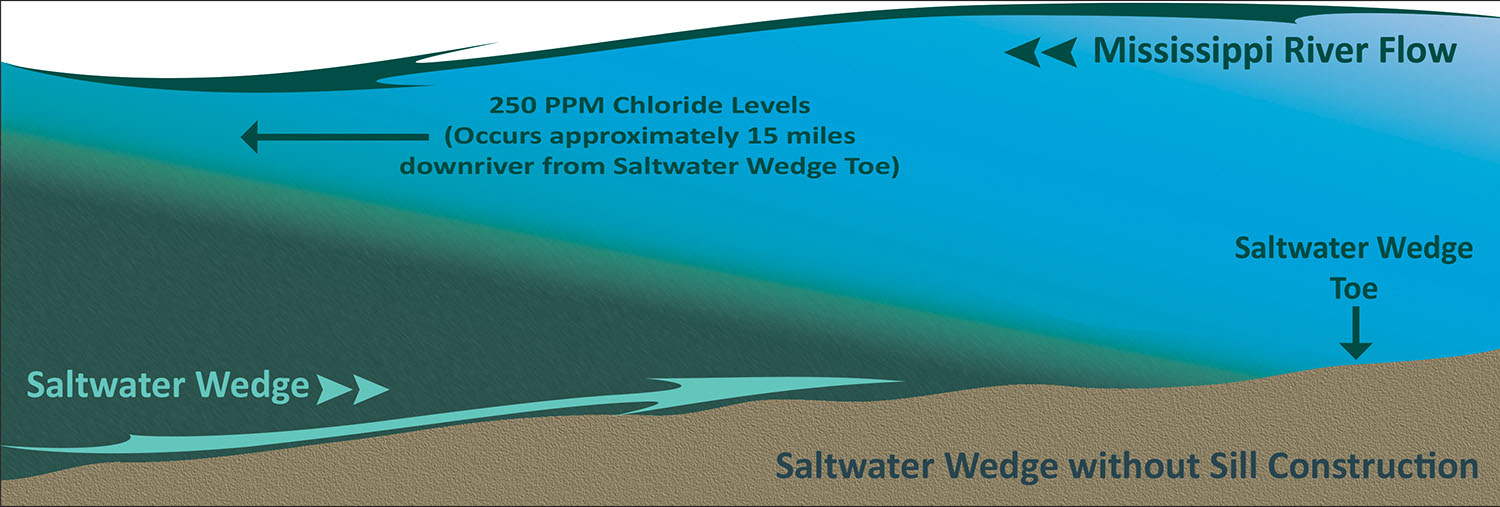

The riverbed on the lower reaches of the Mississippi River is actually below sea level, which means denser sea water is able to push upstream in low-water conditions. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers refers to that influx of sea water as a “salt water wedge,” and since June the wedge has been pushing upriver through Plaquemines Parish, which extends on both sides of the river for its last 75 miles (above Head of Passes).

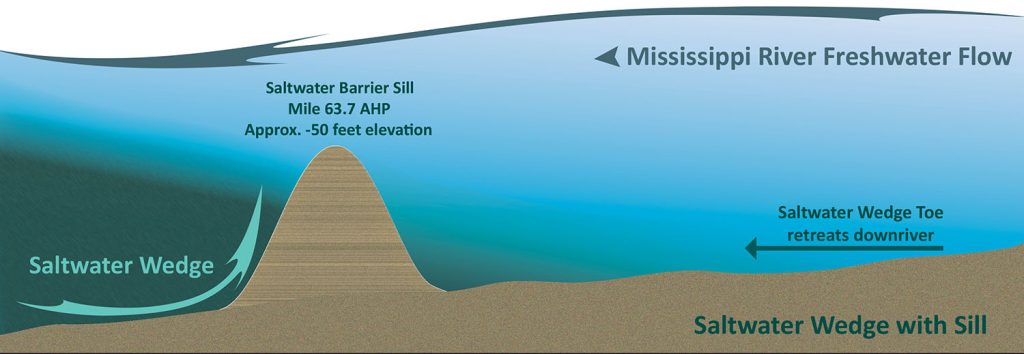

In July, the New Orleans Engineer District began building a sill at Mile 64 to an initial height of -55 feet. At that height, the sill would deflect the leading edge or “toe” of the salt water wedge, while still allowing deep-draft ship traffic to move on the river.

But with the river continuing to drop, both in terms of stage and flow rate, the wedge has continued marching upriver, despite the sill. As of September 21, the toe of the wedge was located somewhere above Mile 66, placing it less than 10 miles below Belle Chasse, the largest city in Plaquemines Parish, and within 20 to 30 miles of St. Bernard Parish and the New Orleans metro area.

According to the Corps, the toe of the wedge stays near the riverbed, with the salt water piling up closer to the surface miles downstream. Thus, while the toe was near Mile 66 on September 21, salinity levels above the Environmental Protection Agency’s water supply standard of 250 parts per million of chloride were approximately 15 to 25 miles downriver.

Ricky Boyett, public affairs chief for the New Orleans District, said it all comes down to physics. With a flow rate of 300,000 cfs. or greater, the Mississippi River is able to push the salt water out to sea.

“Whenever it gets below that, the salt water is able to flow upriver,” Boyett said.

The daytime flow rate at Belle Chasse on September 21 was around 150,000 cfs., while the stage at the Corps’ Carrollton Gage in New Orleans was around 3 feet.

“It is an extremely low river, and it doesn’t have the force to prevent the salt water from moving upstream,” Boyett said. “We simply don’t have the water coming down from the north.”

Low water conditions in south Louisiana extend to even the Atchafalaya River, Boyett said, which receives the entire flow of the Red River, along with 30 percent of the Mississippi River’s flow. During the same time frame, the Atchafalaya had a total flow of 59,000 cfs., with 57,000 cfs. diverted from the Mississippi and only 2,000 cfs. flowing from the Red.

With the wedge moving above the sill, the Corps is preparing to modify the sill to hopefully turn back the salt water, at least temporarily. The river at Mile 64 is about 2,800 feet across, and the Corps plans to increase the height of the sill across much of that to -30 feet. The middle 620 feet of the sill, though, will remain at -55 feet to allow deep-draft navigation. Boyett said quick action is needed to maintain the water supply for the region’s population centers.

“If we do nothing, you could see overtopping of the sill, and you could see impacts to the Belle Chasse water intakes in early October,” said Boyett, who later added, “The only permanent fix is rain. We need real rain to solve the issue.”

Unfortunately, little rainfall is forecast for the Mississippi Valley, and the 28-day forecast calls for the Mississippi River to remain around 130,000 cfs. south of New Orleans.

Boyett said communities in the region faced similar situations in 1988, 2012 and 2022.

“It’s not unprecedented, but we’re close,” he said.

What is unprecedented is seeing near record lows on the river two years in a row.

Boyett added that how to handle drought and extreme low-water conditions will be two of the topics analyzed in the Corps’ Lower Mississippi River Comprehensive Management Study, a five-year study launched in June that will look at how to manage the river from Cape Girardeau, Mo., to the Gulf of Mexico.

In the meantime, though, communities along the river—particularly in Plaquemines Parish—are having to scramble to supply fresh water to residents.

Patrick Harvey, director of the Plaquemines Parish Office of Homeland Security & Emergency Preparedness, said communities between Empire and Venice—about 2,000 residents—saw chloride levels go above safe levels in mid-June. The parish and state both began delivering bottled water to fire stations in those areas on June 23, Harvey said. In addition, the parish installed a booster station in Alliance in order to pipe fresh water to the lower end of the parish. Temporary repairs have also been made at the water treatment station in Port Sulphur, which was damaged in Hurricane Ida. Once online, that station will be able to supply up to 2 million gallons of fresh water per day.

The parish is also working to secure reverse osmosis systems to be located at the Boothville water plant, along with other sites on both the east and west bank of the river, including Pointe à la Hache, Dalcour and Belle Chasse.

Harvey said Plaquemines Parish is also placing reservoir barges on the river near water treatment plants in Port Sulphur, Pointe à la Hache, Dalcour and Belle Chasse.

“Once those reservoir barges are in place, the Corps of Engineers will begin bringing water there for blending,” Harvey said.

Plaquemines is also partnering with neighboring Jefferson and Orleans parishes to tie into their water supply.

With the current advance of the salt water wedge, communities farther upriver are scrambling to secure their own water supplies in time. Without additional rain and higher flows, the wedge could reach Belle Chasse by October 3, St. Bernard Parish by October 8, New Orleans by October 10 and Jefferson Parish by October 11 or 12, Harvey said.

With the river so low, the water plant in Boothville is even having trouble drawing water out of the river, but Harvey said the parish should address that with a bucket dredge by week’s end.

Harvey said he understands there has to be a balance between blocking the wedge while still allowing for ship traffic on the Mississippi River.

“If you stop that, you’re basically shutting down the entire country with the ship traffic,” he said.

Caption for top graphic: Salt water wedge making its way up the Mississippi River. (Corps of Engineers graphic)