If the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season forecast from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is correct, then people named Sean, Tammy, Vince or Whitney can breathe a sigh of relief. They likely won’t share their name with a hurricane or tropical storm this year.

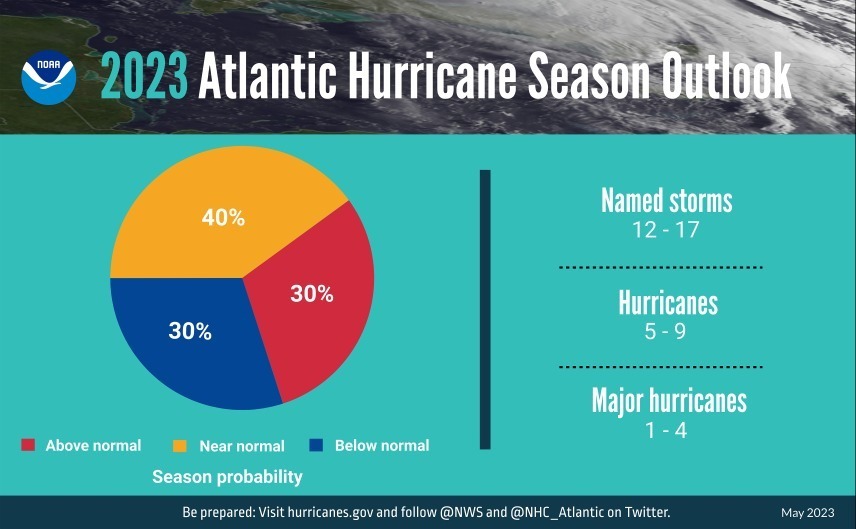

The Atlantic hurricane season runs from June 1 through November 31, and this year, NOAA is predicting a near-normal season. NOAA sees a 40 percent chance of a near-normal season and a 30 percent chance for both above-normal and below-normal seasons.

In other words, NOAA is officially predicting 12 to 17 named storms, five to nine hurricanes, and one to four major hurricanes (with winds of 111 mph. or higher). NOAA officials said they have a 70 percent confidence in those ranges. The NOAA forecast tracks closely with the Colorado State University forecast, released in April, which predicts 13 named storms, six hurricanes and two major hurricanes.

Names one through 17 in the queue for this hurricane season include the following: Arlene, Bret, Cindy, Don, Emily, Franklin, Gert, Harold, Idalia, Jose, Katia, Lee, Margot, Nigel, Ophelia, Philippe and Rina. If the agency needs to go beyond the 21 names already selected, it will forego the Greek alphabet and instead draw from a secondary list of names.

The near-normal forecast stems from the likely development of El Niño conditions later this summer. During El Niño, warmer-than-usual water temperatures in the Pacific Ocean push the jet stream southward and extend it farther to the east, which tends to inhibit tropical development in the Atlantic Ocean.

However, Megan Williams, a New Orleans-based meteorologist for the National Weather Service who spoke May 25 at the annual meeting of the Gulf Inland Waterways Joint Hurricane Team, cautioned that Gulf Coast waterway stakeholders should remain vigilant and prepared in spite of El Niño.

That’s because of above-normal sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic Basin and Gulf of Mexico. Warm water favors tropical development.

“There’s no correlation between El Niño and the Gulf hurricane season,” said Williams, who later added, “I just want everyone to keep in mind that it only takes one, as we all know, so don’t let your guard down.”

The 1992 hurricane season, for instance, was an El Niño season. That year, there were only 10 tropical depressions, seven storms, four hurricanes and one major hurricane. However, that one major hurricane, Hurricane Andrew, which made landfall as a Category 5 storm near Homestead, Fla., and later as a Category 3 storm near Morgan City, La., remains the most destructive hurricane in Florida history based on structural damage.

For this season, the National Hurricane Center will bring online its new Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System (HAFS), which will eventually take over as NOAA’s primary hurricane modeling system. HAFS, according to NOAA, offers a 10 to 15 percent improvement in track forecasting over the current model. Also, the agency’s Probabilistic Storm Surge model received an upgrade in early May, which improves NOAA’s ability to forecast certain flooding scenarios. Flood inundation mapping will improve, as will NOAA’s Excessive Rainfall Outlook, which will not offer five-day forecasts.

Weather watchers this year can also look forward to the National Hurricane Center now releasing its Tropical Weather Outlook graphic, which shows the potential for tropical cyclone formation, seven days out, instead of five days in prior years.

Joint Hurricane Protocol

Following Williams’ presentation, Paul Dittman, president of the Gulf Intracoastal Canal Association (GICA), overviewed the Joint Hurricane Protocol, which guides the partnership between the maritime industry and the U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and other local, state and federal agencies before, during and after a hurricane makes landfall. Two major components, Dittman said, are the Port Coordination Team calls ahead of a storm and the Navigation Restoration Team calls after a storm moves inland.

“Post-storm, if you want to boil it down to its essence, we’re trying to minimize supply chain impacts,” Dittman said, in addition to aiding in search and rescue efforts.

GICA directs four main industry response teams, which all collaborate with waterway managers and emergency responders before and after storms. Those teams include the Incident Command Team; the Self Help Team, which deploys representatives from the maritime industry to help clear queues at various points in the system; the Waterway Assessment Team, which offers survey assistance post-storm; and the Logistics Support Center Team, which helps identify and deploy resources following a major hurricane.

“We don’t get involved with contracting,” Dittman explained. “The idea is to identify who has the gear and who needs it.”

Dittman said the major goal of the annual meeting of the Joint Hurricane Team is the relationships it represents.

“With today’s meeting, we dust off the cobwebs, we reacquaint ourselves and reaffirm our relationships and discuss any changes over the past year, particularly with our military folks and the Coast Guard, with transfers in and out,” he said. “The goal is we want to see seamless coordination for an efficient response and recovery.”

Accentuating the collaborative nature of the protocol, which dates back to Hurricane Katrina, the meeting also featured reports from Coast Guard sectors and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers districts in the region, followed by a time of Q&A.

The plan is available online at gicaonline.com/hurricane-protocol.