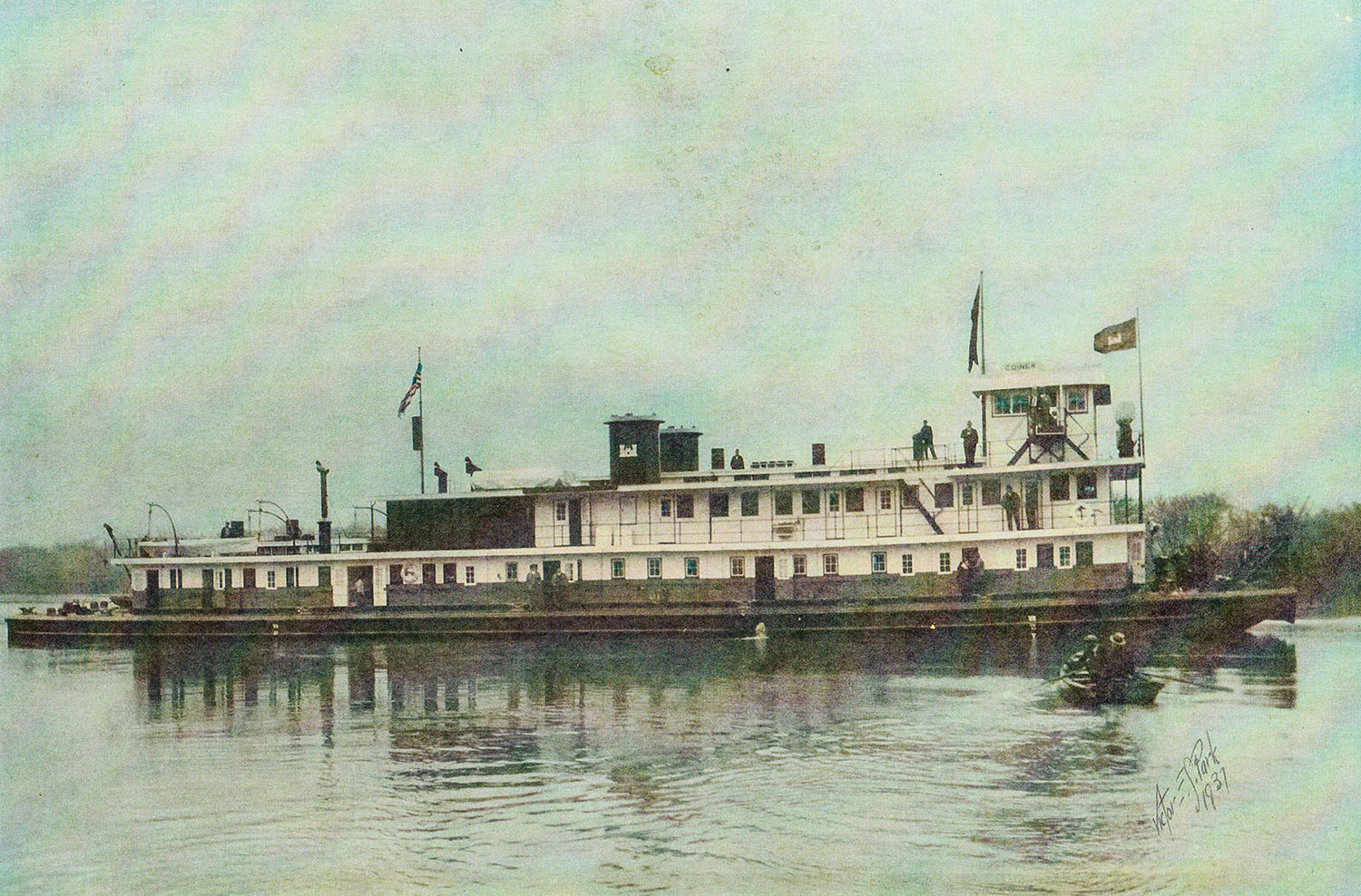

The lead story on page 3 of the February 6, 1935, edition of The Waterways Journal was headlined “U.S. Richard T. Coiner Launched Into Ohio.” It detailed the launch of a new vessel by the Marietta Manufacturing Company, Point Pleasant, W.Va. It said that the vessel went down the ways in “nearly a perfect slide” with the event taking less than 12 seconds to complete. A contingent of “U.S. Engineers officials from Washington, Vicksburg and Huntington” were on hand to witness the launch of the boat, which was described as being 176 by 38 feet with a gross weight of 850 net tons. Once completed it would be assigned to the Vicksburg Engineer District.

A blurb in the New Orleans News column of the March 16, 1935, issue noted that the new Marietta-built towboat Richard T. Coiner would arrive in Vicksburg “within the next few weeks” and that it was named for the late Lt. Col. Richard Coiner, former district engineer in New Orleans. The “Gallipolis Gossip” column of the March 30 issue detailed the trial runs of the boat (still being referred to as the Richard T. Coiner) that had taken place on March 25. The April 6 issue carried a photo of the new boat and said that it had departed at 2 p.m. April 1 for its future home port of Vicksburg. It was now identified simply as “Coiner,” and further details of construction were mentioned, such as it being the first vessel built in many years with a wrought-iron hull, rather than steel to “better resist the corrosive effects of acid in river water.” Also included in the short story was the claim that during trials “the Coiner, while going downstream at 17 mph., was stopped within approximately 50 feet.”

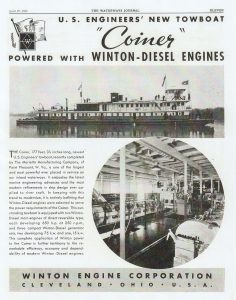

The April 13 WJ contained a detailed description of the new Coiner complete with many photos of the interior of the boat. The engines were reported to be Winton diesels, each rated at 650 hp. at 250 rpm., and were direct-reversible. The four-blade propellers were 7 feet in diameter “of special design to give the boat the best possible towing quality.” While there were no air compressors attached to the engines (as with Fairbanks-Morse engines), there were two 60 cubic foot Ingersoll Rand compressors supplying air to 16 starting air tanks.

Toward the end of the story, the vessel trials were mentioned, and the claim that the boat stopped within 50 feet while traveling downstream at 17 mph. was again repeated. This claim, now twice having appeared in the pages of the WJ, would spark a firestorm of controversy.

Subsequent issues of the WJ would contain letters from people skeptical of the stopping claim. In the issue of May 11, a Capt. J.M. Wells wrote that he felt “someone was a poor judge of distance,” and “this boat is SOME BACKER or else someone should make application for membership to the Liar’s Club.” He ended with “P.S. This boat must be equipped with hydraulic brakes.” Having myself operated a direct-reversible towboat, and it not nearly as large as the Coiner, I can understand the skepticism.

In the May 25 issue, there appeared a letter from W.L. O’Donnell backing the claim. He stated that if it hadn’t stopped in 50 feet as claimed, “then there are a large number of witnesses ready to join the ‘Liars Club.’” He went on to say that the skeptics were probably not aware of the latest devices on the Coiner and said that it was “equipped with hydraulic adjustable-pitch wheels, which can be adjusted from the pilothouse to suit thick or thin, muddy or clear water” and that claims made about the performance of the boat have been “very conservative.” This was the first indication that the Coiner was fitted with variable pitch wheels. There was no mention in the very detailed description of the boat in the April 13 WJ, beyond the statement that the wheels were of “special design.”

The letters both pro and con continued. Austin B. Smith, a civil engineer, went to great length in a letter appearing in the June 22 issue describing the technical aspects of what it would take to allow a boat of the Coiner’s tonnage to stop within 50 feet going 17 mph. In the same issue, Walter T. Gilmore Jr. provided a much simpler theory by saying “a ‘good ole sandbar’ will stop her within 20 feet.”

The very best summation of the event appeared in the July 6, 1935, issue in a letter from J.C. Lever, an associate engineer in the Lower Mississippi Valley Division, U.S. Engineers. He had been aboard the Coiner during the trial run in question and offered an in-depth explanation of what had transpired. He stated that when the boat was 200 yards below the Point Pleasant bridges, running full ahead at 275 rpm. and making some 17 mph. assisted by a 2.5 mph. current, the rudders ran hard down to starboard when a circuit breaker overloaded. The pilot rang for full astern and the boat, swerving to starboard, traveled downstream 100 feet and the bow was some 30 or 40 feet from shore when both engines were backing on a “double gong” of 300 rpm. The bow brushed through the willows but was not felt to have touched the bank. The boat began to back away from shore, and the engines were stopped and the boat allowed to drift while the steering circuit breaker was re-engaged.

In his final paragraph, Lever said, “Should it be considered that the boat stopped in 50 feet or did the boat stop within 350 feet represented by the distance between the point where the rudders jammed and the headway was killed? Suppose you take a guess at it as everyone else appears to be doing.” He ended the letter with “Yours, for more facts and less fiction, J.C. Lever.”

In the August 17 issue was a note from Wm. J. Ward of the Winton Engine Corporation, Cleveland, Ohio, saying that he had enjoyed clippings of the discussion sent him by the WJ. In the midst of all the furor, Winton had been running full-page ads in the WJ featuring the new Coiner.

The Coiner would go on to spend an entire career with the Engineers, without any further “controversy” in evidence. It was eventually transferred to the Memphis District of the Corps of Engineers and, in 1961, was repowered with a pair of GM 12-567A diesels totaling 1,800 hp. They were paired with Falk 2.5:1 gears. In 1982 it was sold to McAlister Construction Company, Memphis, and removed from service. Its final disposition is unknown by this writer.

Caption for top photo: Colorized photo of the Coiner on trials that hung in MMC offices. (Photo given to author by Capt. Nelson Jones)