This year’s extreme drought and resulting low water on the Mississippi River got national and worldwide attention. On December 14, top leaders of the Corps of Engineers, Coast Guard and the towing industry came together to focus some of that attention where it belonged: on the men and women of the dredging crews who worked day and night to keep shipping channels open during the most severe low water in recent memory—and are still working. The event was organized by the St. Louis Engineer District. The message conveyed to those crews was, “What you do matters.”

Guests gathered at the St. Louis District Service Base at the foot of Arsenal Street, St. Louis, where they boarded the Corps support vessel mv. Pathfinder and toured St. Louis harbor en route to the Cargill terminal in East St. Louis. Their host at the Cargill Terminal was Jeff Webb, president of Cargo Carriers and vice-chair of Waterways Council Inc., who led a strategic discussion on current and long-term impacts of the low water conditions. The Cargill terminal is used by more than 500 local farmers to ship their grain. “To see three dredges working in and around St. Louis was just fantastic,” Webb said. “Everyone was trying to make this as good as they could in a very difficult, trying situation.”

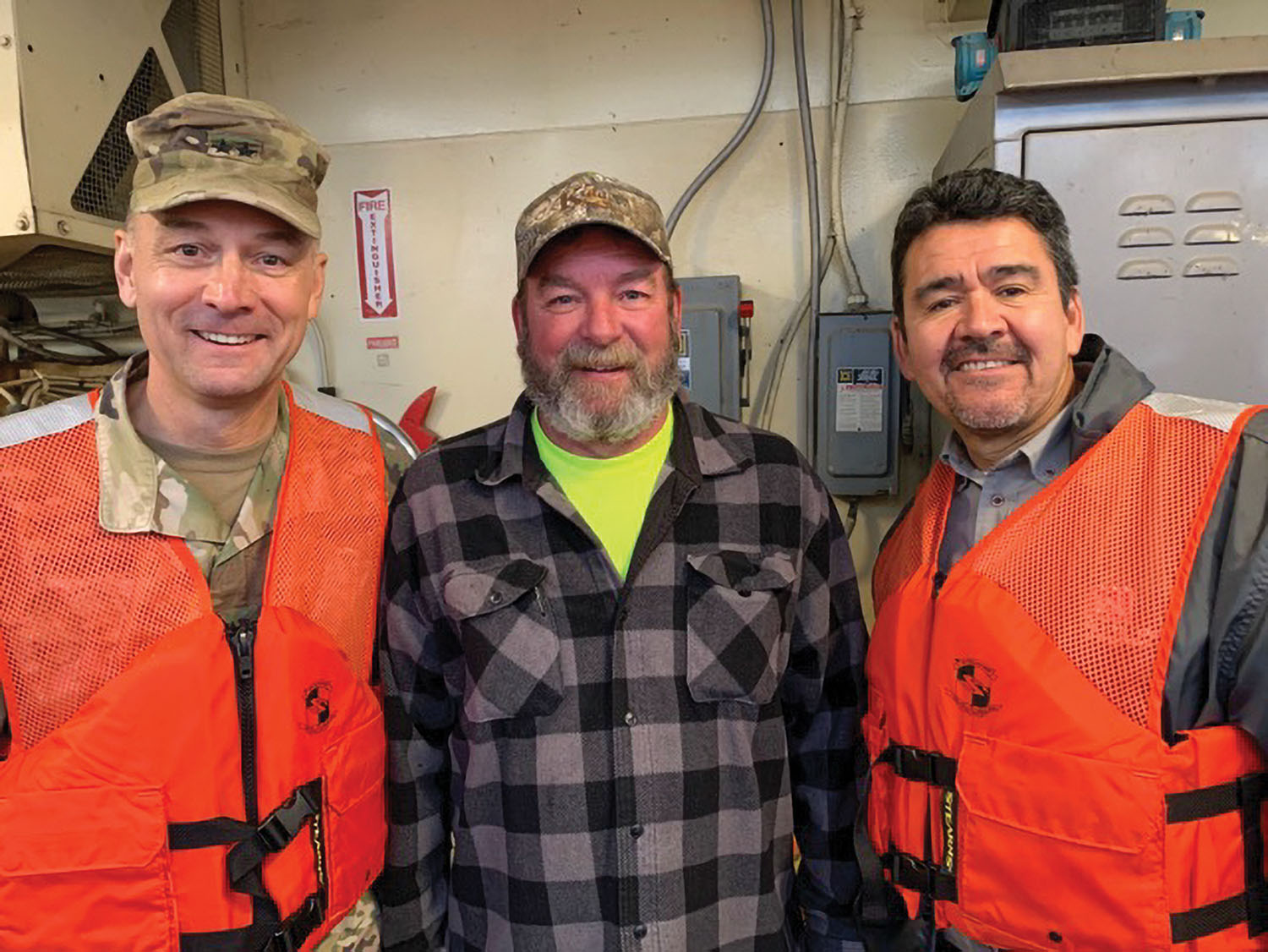

Leaders from Corps Headquarters present included Michael Connor, assistant secretary of the Army-civil works, and Maj. Gen. William “Butch” Graham, deputy commanding general for civil and emergency operations. St. Louis District representatives included Lou DellOrco, chief, operations, regulatory and readiness; Andy Schimpf, navigation business line manager; and dredging manager Lance Engel. The Coast Guard had several representatives present, including Capt. Andrew Bender, commander of Sector Upper Mississippi and captain of the port.

Industry representatives included Bernie Heroff, current chair of the River Industry Action Committee (RIAC) and a port captain at American River Transportation Company, and Marty Hettel, vice president-government affairs at American Commercial Barge Line and a member of the Inland Waterways Users Board.

The Pathfinder then took guests to the dredge Potter, about a one-hour trip, where it was working near the JB Bridge (Upper Mississippi Mile 171). There they had a late lunch with the dredge crew and toured the vessel. Paul Rohde, vice president-midwest area for WCI, said after observing the two-person bridge crew operating the boat and cutterhead, “It brought home to me how many moving parts there are to a dredging operation—literally. There are a lot of dials and numbers to keep track of on the bridge of a dredge.” The total crew of a cutterhead dredge like the Potter is about a dozen, including pilots, dredge operators, cooks and engineers. During the low-water crisis, crews work 12-hour shifts.

The dredge moved aside for a passing tow at one point, Rohde said. It illustrated the close cooperation between industry, the Coast Guard and Corps of Engineers during the low-water operations, which are still ongoing despite some recent rains that have raised river gages somewhat. The Coast Guard is responsible for setting buoys and markers in the dredged channels.

“We have improved communication of channel conditions to ensure that all waterway stakeholders have a common operating picture of the status of the channel,” DellOrco said. “We provide real-time availability of survey data and get real-time feedback to plan and coordinate the efficient movement of dredges. The RIAC, Corps and Coast Guard team meet regularly to discuss and resolve issues.”

The 240-foot-long, 46-foot-wide dustpan dredge Potter was originally built in 1932 at the height of the Great Depression; this year’s dredging season is its 90th. Some of its parts are so old that replacement parts must be milled from scratch by the Corps in special machine shops, since the original manufacturers have long ago gone out of business. In recent years the Corps has turned to 3D printing for some parts.

There was a brief “challenge coin” ceremony, in which Corps leaders handed out special commemorative coins to crewmembers while towing industry leaders thanked them personally and shook their hands. One cook on the mv. Pathfinder was overcome; it was her last day before retirement, according to one participant. Challenge coins to commemorate noteworthy events are a tradition across all five branches of the military services.

The next day saw a similar agenda for the 20-inch cutterhead dredge Goetz and the self-propelled dustpan dredge Hurley, with guests joining the Goetz crew for breakfast. They crossed the river at Perryville, Mo., toured the Kaskaskia Lock and Dam at the mouth of the Kaskaskia River and discussed low-water tonnages before boarding the Hurley via crewboat from the lock and dam.

The Hurley, stationed at the Memphis Engineer District, was originally built in 1993 and could dredge up to 40 feet deep. After a few years in service, Corps officials realized there was a need to lengthen the dredge to dig deeper to help water commerce on the lower end of the river. In the late ’90s, the Corps began developing plans to lengthen the dredge from 205 to 353 feet in order to dig up to 75 feet deep. Corps shipyard workers lengthened the Hurley and installed new equipment, completing the work by 2010.

While the world’s attention will fade as waters return to a more normal level, the work of the dredging crews never stops. “One of the things that Lou [DellOrco] opened my eyes to was the amount of preventive dredging that takes place all the time,” Rohde said. “The riverbed is always shifting and changing, and the goal is always to address problems before it’s necessary to close any stretch of river.”

As bad as the recent low water was, DellOrco said, without the work of the dredging crews, “It could have been a lot worse.”

Caption for photo: From left, Corps Deputy Commanding General William “Butch” Graham; Brian Ragsdale, master of the Dredge Potter; and Assisstant Secretary of the Army-Civil Works Michael Connor. (Photo courtesy of St. Louis Engineer District)