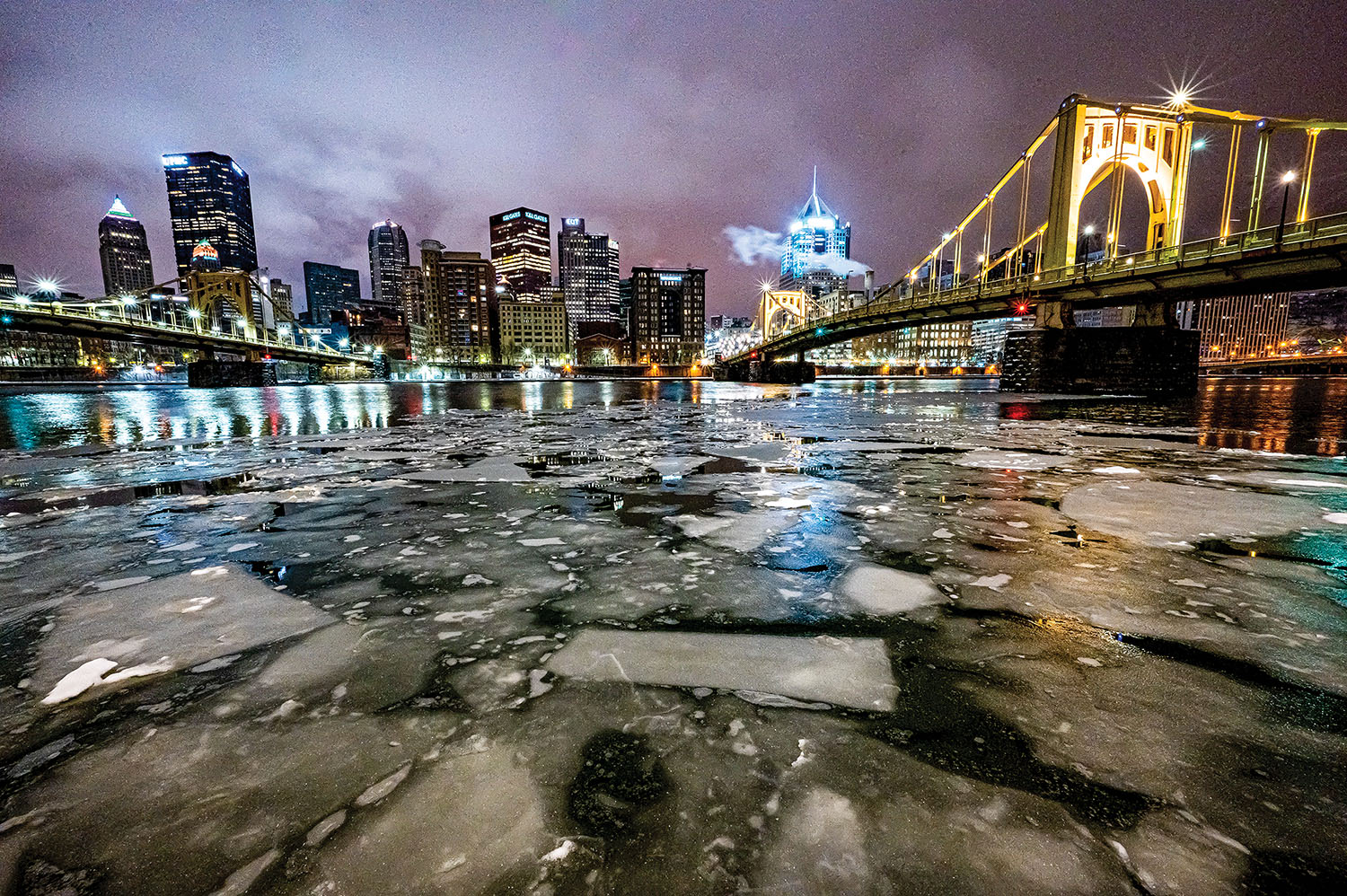

A collaborative team of government and industry professionals helps prepare for ice and high water in the Pittsburgh, Pa., region before it happens.

Known as the Ice Hydro Committee, its members are dedicated to making sure those involved with the river industry in any way know the best information about potentially hazardous conditions before they form.

John Dilla, chief of the Locks and Dams Branch for the Pittsburgh District of the Corps of Engineers, said the team has been around at least a decade, although it now uses newer technology, such as Microsoft Teams videoconferencing software and digital monitoring systems.

The U.S. Coast Guard’s Marine Safety Unit Pittsburgh leads the meetings with input from the Pittsburgh Corps of Engineers, the Waterways Association of Pittsburgh, the National Weather Service and other navigational partners. Beginning in November or December, the team begins meeting once every other week, but their schedule varies along with the weather. Sometimes, Dilla said, it’s several times a week or even daily.

“We are reacting to Mother Nature, so we do what we have to do for that,” Dilla said.

Occasionally, team members meet on the weekends or during the evenings.

“Everybody’s just all in out there to make sure we keep everybody out there safe,” he said.

The committee tracks data from weather forecasts, navigation reports and even individual alerts received from the public and distributes information to key stakeholders.

“It’s definitely a meeting that has grown out of need,” said Megan Gottlieb, Water Management Unit lead for the Pittsburgh Corps of Engineers. “It’s a very quick but beneficial meeting.”

Although the team starts meeting in preparation for winter weather, the meetings typically continue through the spring.

“It’s not just ice,” Dillas said. “It’s all weather or river conditions that could affect safe navigation.”

Typical meetings begin with National Weather Service weather predictions for upcoming days or as far out as a week. The National Weather Service also uses data from U.S. Geological Survey river gauges, and the Corps has information from its Lock Performance Monitoring System.

Members from the Corps often talk about impacts to local locks because of expected closures, as well as what those working at the locks are seeing in terms of drift and ice. Navigational partners often point out what they are seeing in the channel away from the locks and dams. Such meetings could include talking about ice building on a bend or how much storage is available in a reservoir to deal with a forecast of heavy rain upriver that could cause flooding downriver. Much of the information discussed by the committee is distributed by the Waterways Association afterward via email.

The Pittsburgh region’s infrastructure is unique. Dams on the Allegheny are fixed-crest, which means water flows over the top. Therefore, large chunks of ice continue floating downriver with minimal obstruction. Once ice reaches the upper Ohio River, however, most of those locking facilities have gated dams that block ice from moving downstream. That can cause a major backup, with pieces of ice stacking on top of each other.

“The deeper it stacks, the more that it gets to be a problem,” Dilla said.

When tows are moving downriver, they push not only through the ice but sometimes over it, he said.

“The ice moves underneath the barges and in front. So they are pushing massive amounts of ice underneath them and in front.”

When a tow stops to lock through a dam, that ice often comes out, and lockmasters sometimes require extra lockages to flush ice downstream in an otherwise empty chamber. Those extra lockages add delays for tows transiting through the chambers.

Dilla described this season as an “average” winter. At first it was milder than usual, but then got cold fast, which built ice quickly, he said. Key factors team members watch are temperature and time. If the average temperature reaches below 22 degrees Fahrenheit over 24 hours, it is a strong indication that ice will form.

January and February are typically the worst months in terms of icing, Gottlieb said. After that, the team gets ready for the typical higher water that comes with the spring as the ice and snow melt and spring rains set in.

“We definitely don’t want to see 60-degree weather in March because then the snow melt and the high water just come together,” she said.

Instead, the committee hopes for a string of 40-degree days to slowly melt the ice.

Gottlieb said the Ice Hydro Committee meetings are particularly useful because every organization has a stake in ensuring safety along with continued navigability of the system, although they all have different roles. The meetings help them think from other people’s perspectives and have a proactive role in managing and responding to various river conditions.

“It’s critical that we come together and share this information,” she said. “We all work in our own lane really well, and coming together, we are able to do more.”

Caption for top photo: Ice forms on the Allegheny River in Pittsburgh, Pa., on January 25. Ice is a recurring concern in the winter for industries that rely on navigation to transport commodities. To get ahead of navigation impacts, the Ice Hydro Committee is composed of members from the Coast Guard, Corps of Engineers, National Weather Service, the Waterways Association of Pittsburgh and other stakeholders. (Photo by Michel Sauret/Pittsburgh Engineer District)