In the early days of my river interest during the 1960s, it was my good fortune to become friends with Capt. Harris Underwood (1898-1982) who served as pilot of the Belle of Louisville. Underwood came from a well-known family of steamboat officers, including his father and brother. It was always thrilling to sit on the pilothouse bench and listen to stories of his exciting river experiences. The recent weather tragedies in western Kentucky recall a true story.

In the spring of 1921, the Underwood brothers, Harris and Paul, were engaged to take the packet James N. Trigg from Chattanooga south on the Tennessee River to Lamb’s Ferry, Ala. This was Paul’s first trip as a steamboat master. The pilots were Capt. Harris Underwood and Capt. Ike Lambert, with Corky Eldridge as chief engineer, Bob Allison, mate and Olin Chandler in the clerk’s office.

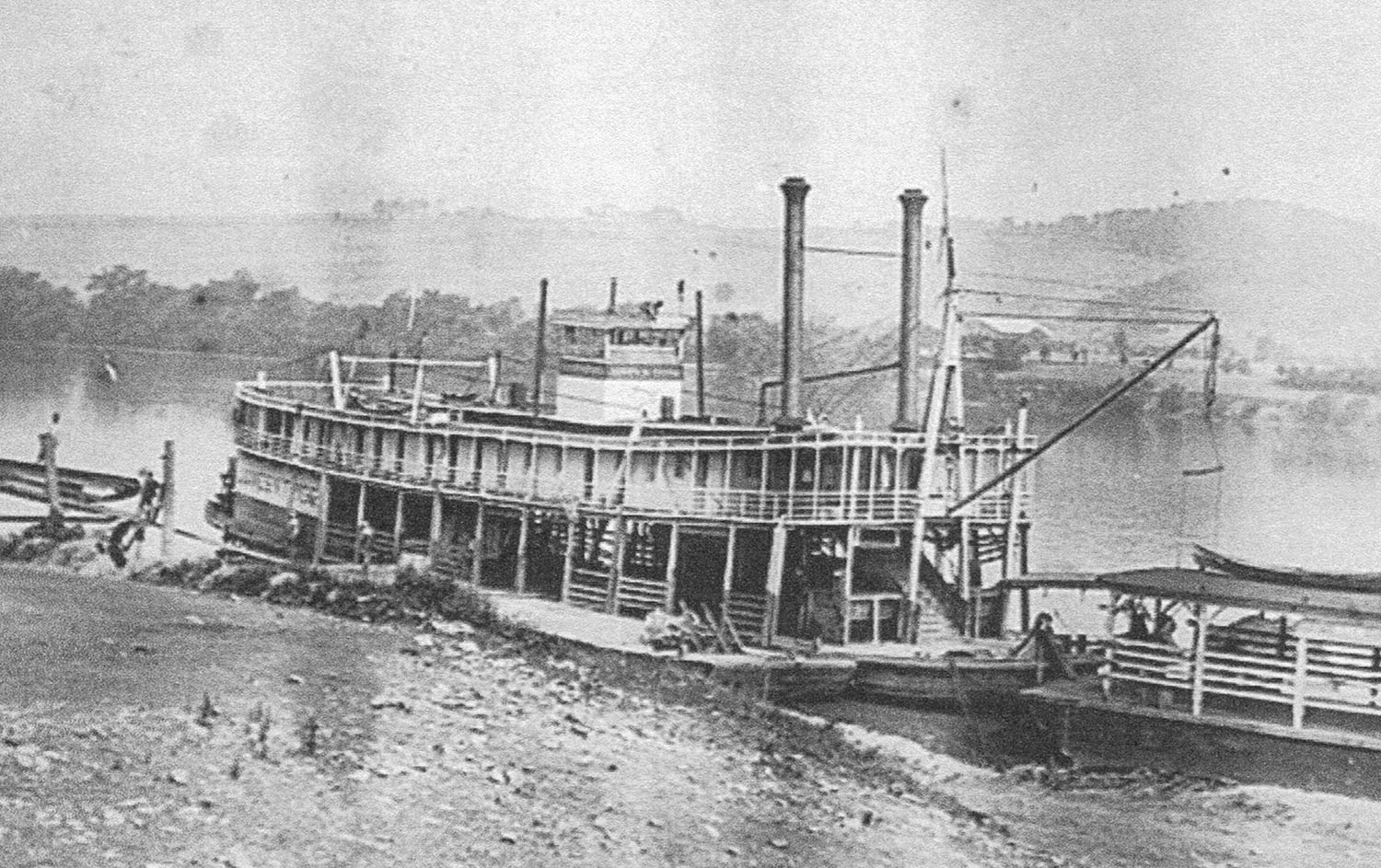

The Trigg was a trim sternwheeler, built in 1910 at Decatur, Ala., on a wooden hull that was 158.2 feet in length and 28.2 feet in width, with a depth of 4 feet. Two boilers supplied steam to engines having 14-inch cylinders with a 5-foot stroke. Owned by the Tennessee River Navigation Company, the boat operated in the Chattanooga-Kingston trade. Although considered a packet boat, the vessel was outfitted with towing knees and often pushed flats.

The Trigg departed Chattanooga, towing a covered barge, struggling against heavy rain and gusty winds. Some 5 miles above Hobb’s Island, a tornado ripped across the river directly in front of the steamboat, with the force of the wind blowing the riverboat and barge ashore. Half of the Trigg’s cabin was demolished; Capt. Lambert fell through the pilothouse floor into the boiler deck cabin, still grasping the pilotwheel. A terrified passenger fled from his room and desperately held onto a hogchain to keep from being blown overboard. The twin smokestacks were knocked down and flattened. The lighting plant of the boat failed, and an overturned cookstove started a fire that was quickly extinguished. Shortly thereafter, lines were run to shore, and all were relieved to learn that no lives had been lost.

The crew returned to Chattanooga by train and came back to the scene aboard the towboat Captain Lyerly, also owned by the Tennessee River Navigation Company and constructed in 1921, largely from recycled parts of the packet Joe Wheeler, including the whistle. The Lyerly departed with the barge, leaving the damaged steamboat tied to the bank.

While landed to load a carload of fertilizer, one of the roustabouts walked off the barge in the dark and drowned. Another stop was made at Decatur, Ala., to deliver the fertilizer before proceeding on to Lamb’s Ferry. Along the way, several bootleggers were encountered in a yawl, and each of the crew purchased a jug of whiskey.

The Lyerly later took the Trigg, whose boilers and engines were in working order, in tow for the return to Chattanooga, with the engines of both boats providing the propulsion. Harris Underwood was known as a “double ender” (possessing both pilot and engineer’s licenses) and, as the lone person aboard, presided in the engineroom of the Trigg. At Oate’s Island, the boats came too close to a reef, and the Trigg was broken loose from the tow. As Harris related, “It was high time for a little panic!”

The Trigg never ran again and was immediately dismantled at the Chattanooga wharf.

Caption for top photo: The James N. Trigg at the Chattanooga wharf. (Keith Norrington collection)