Purple lightning, swirling river fog and then total blackness were the signs Douglas Lewis noticed moments before a monster tornado crossed a few yards from his towboat.

The same tornado that preliminary surveys show could be one of the longest-tracked tornadoes in the country’s history crossed the Mississippi River near Caruthersville, Mo., at 8:23 p.m. December 10, according to the timestamp on Lewis’ phone.

Lewis, a 35-year-old deckhand and Navy veteran on Marathon Petroleum’s mv. Mt. Vernon, was sitting in the galley, talking on his phone to his wife, Kayla, and 4-year-old son, Garion, when the phone went dead. It would be hours before he could reach them again.

The Mt. Vernon was northbound when the increasingly concerning reports of a tornado on the ground nearby caused Capt. Keith Fowler to shove its tow of nine empty barges into the bank at Mile 859.78. He had already warned Lewis that Lewis might have to wake up the entire seven-member crew so they were prepared to respond, and the captain gave the order to do so at the same time as Lewis’ call dropped.

After waking sleeping crew members, Lewis reached for his phone again. When he still couldn’t make contact with his family, he turned to his hobby, creating and editing video, at first with an eye to showing them what had happened. He took several short videos of what he was seeing and eventually edited them and a few still images all together.

Still unaware of the tornado’s eventual impact, he later posted the video to a Facebook group.

“After the fact I thought, hey, people might want to see this,” he said. “The lightning looks cool.”

He was shocked when within a few days it garnered more than 1,700 views, and more than 800 people had shared it.

The five-minute, 26-second video begins with a radio call from the captain, telling crew members to make sure they are all wearing their life vests. Lewis explains they have just heard the report of a “tornado emergency,” one step up from a tornado warning, from the National Weather Service. The broadcast notice indicated a life-threatening emergency and said to seek shelter.

Thunder rumbles and rain pours as Lewis narrates, “We’re shoved in here to the bank, and it’s coming down on us, but we’ll probably be OK.”

Moments later, he shows the swirls of pendulous, smoke-like river fog, calling it eerie.

“It’s supposed to cross the river right here where we’re at,” he says, then pauses a second or two as lightning illuminates the sky.

“I think that’s it, over there where it’s real dark,” he said. “So we’ve got a front-row seat.”

Thinking back on it now, everything happened quickly, Lewis said. “Between waking everybody up and it being on top of us, it was probably only 5 or 10 minutes.”

The sky lit up purple, making it appear the lightning itself was purple.

“I had never seen purple lightning before,” he said.

Rising fog looked like steam bubbling up, at first swirling, and then moving in odd patterns.

“All of that steam that was coming up around the boat was whipping around really fast to the west side,” he said.

At first, there didn’t seem to be a defined funnel cloud, but Lewis realized even though he was in a room with windows, the middle third of his vision was staying black.

“I just went across the radio and said, ‘Here it comes,’ ” he said.

In a lightning flash, he delineated the funnel. Lewis kept his phone pointed toward it and the video rolling. Between lightning flashes it looked like it wasn’t moving. Then he realized, “It looks like it’s sitting still because it’s coming right for us.”

When the funnel moved off the riverbank and onto the water, blackness enveloped the boat, and even lightning no longer penetrated. But although he couldn’t see much, Lewis could still hear. “It hit that water, and you could hear it roar,” he said. “It just picked up steam as it was going across the water.”

The crew got into the hallways in the center of the boat, away from all the windows.

“But it didn’t break any windows or anything,” he said. “It shook really bad for about 30 seconds.”

He had the thought to try to crack open the door to equalize air pressure, as he had been taught to crack open a window in his childhood home in Missouri when tornadoes were close by.

“The wind is so strong I can’t open the door,” he says on the video. “It’s just holding it closed, and it’s coming right over the top of us.”

Then, silence.

“It killed the engines as it was coming across, sucked the air out of the intake of the engines. It blew open the engine room doors from the mess area.”

“The lightning came back,” Lewis said.

When the wind died down enough to venture outside, the crew found eight lines had separated, rigging covered the deck, and the 1-inch-thick aluminum jackstaff for the flag was bent in half.

Deck boxes containing life vests were no longer in place.

“It took those boxes and just chucked them into the water,” Lewis said.

He noticed their safety lights flashing in the dark water as they floated downriver.

All in all, “the boat held up really well,” he said.

No one was hurt.

It was the second time this year the twin-screw, 6,000 hp. towboat has faced nature’s wrath. The Mt. Vernon was tied up at a refinery in Garyville, La., during Hurricane Ida August 29. It endured four hours of 100 mph.-plus winds, moments of calm as the eye moved over it and then four more hours of pummeling.

Having lived through a hurricane, the extent of the tornado’s destruction was surprising to the crew.

“When we went to leave the next morning we were able to pull out and look at it and were just amazed how wide it was,” Lewis said.

Estimating by the 900 feet of their tow and 150 feet of their boat, they determined the base of the tornado must have been about 2,000 feet wide. Preliminary reports from the National Weather Service showed the crew underestimated slightly. The NWS indicated the tornado was about 3/4 of a mile wide, or 3,960 feet.

It stripped trees bare of leaves both in front and behind them along the riverbank. Fallen trunks were thrown against the head of the tow, roots and all.

“If we would have been 1,000 yards in either direction we wouldn’t have been in its direct path,” Lewis said.

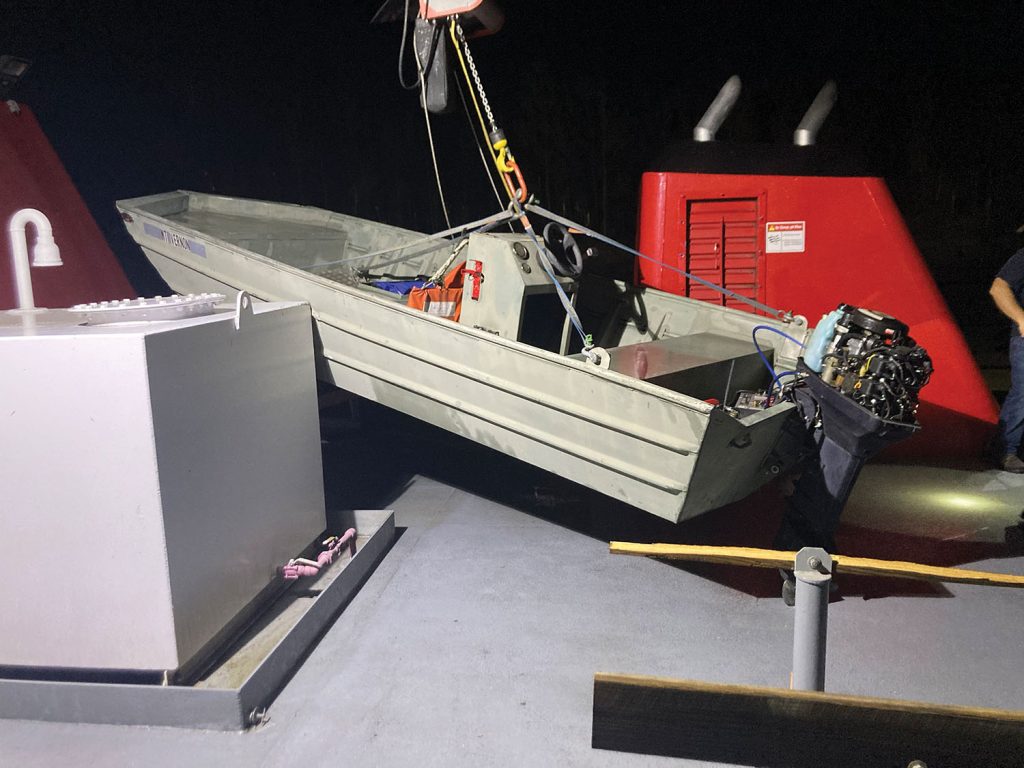

The whipping wind wrecked the boat’s grills and smokers. The worst damage was to the yawl, the small, metal jon boat that normally stays attached to a crane and rests on its own stand on the deck.

“It threw the yawl about 20 feet into the intake stacks and popped a hole through it,” Lewis said.

Exposed wires protruded from the outboard motor. The broken rudder dangled.

Eventually, Lewis climbed to the wheelhouse and looked at instrumentation showing the highest wind speeds the towboat had encountered.

That, too, is recorded with an image in the video. “We clocked it at 121 mph.”

Caption for top photo: Douglas Lewis was on the Marathon Petroleum towboat the mv. Mount Vernon with its tow of empties shoved up against the bank when the tornado that decimated towns in four states and killed more than 60 people crossed the Mississippi River. (Photo by Douglas Lewis)