By the early part of the 20th century, railroads had all but decimated river transportation, in particular barge towing. Other than certain trades, such as the steel industry in the Pittsburgh area, few towing vessels were active on the rivers. When the U.S. entered World War I, it became readily apparent that river transportation wasn’t only needed, but that it was vital, yet barely existed.

Following the conflict, Congress took a hard look at the situation. What resulted was the Transportation Act of 1920, and ultimately the formation of the Inland Waterways Corporation (IWC), in effect a government-owned barge line that was intended to revitalize river transportation. Maj. Gen. Thomas Q. Ashburn became the head of this organization, and the general took his job seriously — so seriously that the railroads hated him!

The IWC, becoming known among the river fraternity as the Federal Barge Line, began with boats that were purchased or requisitioned from other government services, while new equipment was planned and constructed.

General Ashburn’s IWC was bold in embracing emerging technology, and steam propeller towboats were the first constructed. In 1920, the Howard Ship Yard and Dock Company, Jeffersonville, Ind., built a series of boats intended for the Mobile and Black Warrior rivers. These were the Cordova, Demopolis and Montgomery, which were 800 hp. and measured 140 by 24 feet. A larger series of steam prop towboats for the Mississippi River system were built in 1921. These boats, 1,800 hp. with dimensions of 200 by 40 feet, became known as the “City” boats and were built by two West Virginia shipyards. The Marietta Manufacturing Company, Point Pleasant, W.Va., built the Baton Rouge, Cairo, Memphis and St. Louis, while the Charles Ward Engineering Works, Charleston, W.Va., constructed the Natchez and the Vicksburg. Several traditional steam sternwheel towboats were also built for the IWC.

Diesel Making Inroads

Diesel power was making inroads in river transportation during the 1920s. The Ward yard-built boats for the Kelley Line were mentioned earlier, and the Nashville Bridge Company had built some diesel-powered prop towboats of sizes comparable to the Geo. T. Price and W.A. Shepard. Dravo had churned out several small diesel sternwheelers, as had other shipyards and individuals. It was only natural that General Ashburn and the IWC would begin looking at diesel power, and when they did, as the late Jim Swift termed it in his Backing Hard Into River History, they did it in a big way.

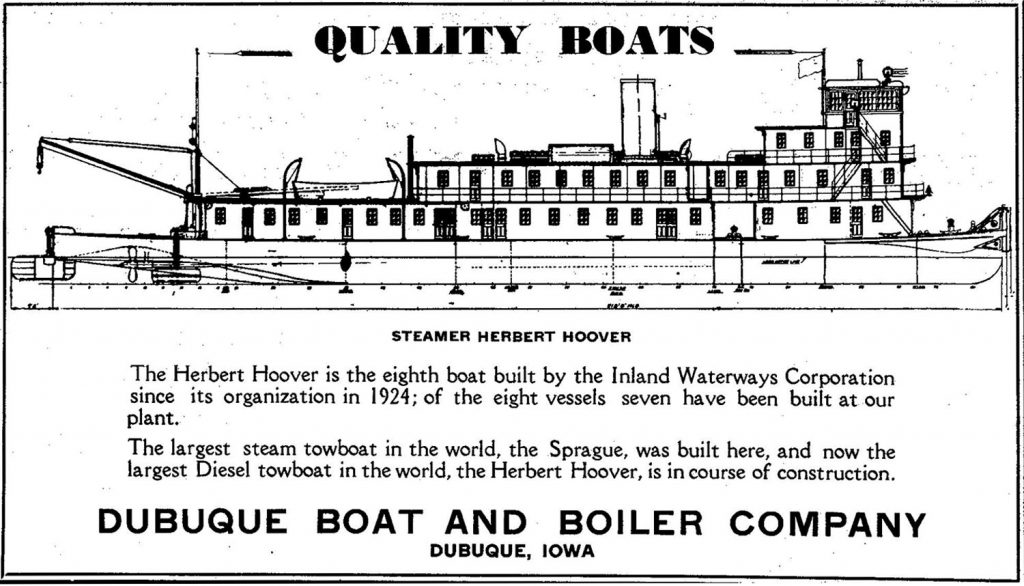

In 1930, the Dubuque Boat & Boiler Company, Dubuque, Iowa, began running ads in The Waterways Journal depicting a profile drawing of a large propeller towboat. Immediately under the image of the boat were the words “STEAMER HERBERT HOOVER,” yet further down in the ad was the statement “The largest steam towboat in the world, the Sprague, was built here, and now the largest diesel towboat in the world, the Herbert Hoover, is in course of construction.” The drawing shows what is today an unusual rudder setup, with the steering rudders on a post at the stern, much like sternwheel boats. Photos of the boat under construction and in early operation do not show these rudder posts.

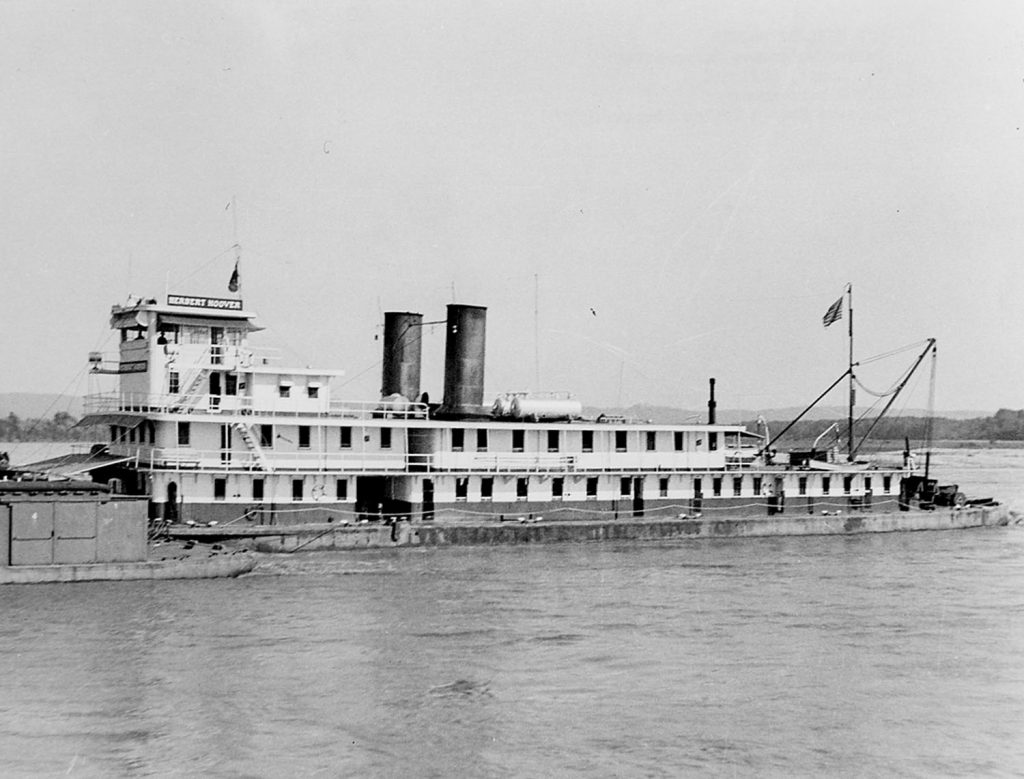

A small story in the August 16, 1931, New York Times carried this headline: “THE HERBERT HOOVER LAUNCHED AT DUBUQUE; World’s Largest Diesel Towboat for Mississippi River Is Named by Mrs. T.Q. Ashburn.” Mrs. Ashburn, of course, was the wife of Gen. Ashburn. No surprise that the big boat was named for President Hoover, since most other boats built by the IWC had been named for government officials. But looking further into Hoover’s background, it was very appropriate that it bear his name. Hoover had long been an advocate of the river system. He had become aware of the amount of freight carried by European rivers following World War I, and thereafter became a supporter of improving the navigable waterways of this country. As the secretary of commerce under President Calvin Coolidge, Hoover was much in favor of the Missouri River improvements and the construction of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway. He also championed flood control and navigation projects on the Lower Mississippi, including cutoffs.

The Herbert Hoover was large by any standard, measuring 215 by 43.5 feet with a 10-foot depth of hull. A pair of McIntosh & Seymour diesels described as four-cycle, eight-cylinder, 20-inch bore by 24-inch stroke delivered a total of 2,200 hp., making it the most powerful diesel towboat on the rivers at that time. Its props were 8-foot diameter by 77-inch pitch. Interestingly, Capt. Fred Way, in the initial 1945 issue of the Inland River Record, stated that the Herbert Hoover was built from Dravo designs. Photos show that its red and green running lights were hung from its large stacks in steamboat fashion, and the front of the pilothouse was fitted with a browboard and breastboard.

Attracted Attention

As the boat entered service, it attracted a lot of attention. Throughout the first year of operation, it was mentioned often in the news columns of the Waterways Journal.

In the February 20, 1932, issue, the Memphis News column written by Ed McLeod said, “The Herbert Hoover was in and out from both directions. Along with the big Minnesota, she’s running through to Cairo, then back south to turn back the New Orleans boats. Both are handling a lot of tonnage.” In the same issue, the ad for the Dubuque Boat & Boiler Company now featured a photo of the boat, rather than a drawing.

In the October 15, 1932, issue, the same column refers to the Herbert Hoover as “The Federal Line flagship,” noting that it was “out” from New Orleans after having some repair work done. The column goes on to say that the boat was in the command of Capt. George O. Rogers, with Capts. Harry P. Silbernagle and R.J. Zang as pilots and John Bridgewater as chief engineer.

After the U.S. entered World War II, for whatever reason the Hoover was laid up, and remained so for most of the war, becoming one of the few big boats to do so. It is not known if this decision was due to personnel shortages, mechanical parts availability or some other reason. One of the few other large boats to be tied up during the war was the large sternwheel steamer Charles F. Richardson, which had been sold by the West Kentucky Coal Company to the Mississippi Valley Barge Line in 1942. However, while the Richardson would never again operate, the Hoover would.

New Orleans

In February 1948, the Hoover was sold to the Mississippi Valley Barge Line Company of St. Louis and renamed New Orleans. It was taken to the Dravo yard at Neville Island, Pa., where its original engines were replaced by a pair of GM 16-278A diesels totaling 3,200 hp. Kort nozzles were added by St. Louis Ship in 1950.

Despite the improvements made, the New Orleans did not have a great reputation for handling. Capt. Norman Hillman mentions it at length in his autobiography One Man and the Mighty Mississippi. He says that among the Valley Line pilots she was known not so affectionately as “Old Rags.” Hillman details some harrowing times while piloting the big boat down a swollen Ohio River, and another time when he was on her southbound above Cape Girardeau. While following the Ohio River trip it was discovered that a rudder was missing, Capt. Hillman said that the New Orleans “could make good pilots cry even when she was in good shape.” He also said that he felt the company had made a mistake by not keeping the boat just to train young pilots.

In a sense, the river industry also outgrew the big boat. For many years, a standard cargo barge had been 175 by 26 feet, but as the years went on, they had grown to the size of 195 or 200 by 35. Too many 200-foot-long barges, and the boat couldn’t lock on the end of them.

The New Orleans last appeared in the 1965 Inland River Record. Capt. Bill Judd of Cincinnati says that he recalls it laying a long while at the Valley Landing at Cincinnati but does not recall its final disposition. Hopefully the once impressive and groundbreaking vessel continued to serve in some capacity, such as a landing boat somewhere, rather than being simply scrapped. Quite a few steam sternwheel towboats were built after the Herbert Hoover went into service, but it outlasted them and ultimately helped usher in the true era of diesel power on the rivers.

Caption for top photo: The Herbert Hoover under construction at Dubuque Boat & Boiler Company. (Dan Owen/Boat Photo Museum collection)

The author wishes to thank Barry Griffith, Jeff Yates, Tom Waller and Fran Mullen for their help with photos.