By 1929, great strides had been made in the Western Rivers towing industry regarding diesel propulsion. Many small diesel sternwheel boats were in operation, as well as the fairly large Duncan Bruce, built by Ward in 1927 with twin sternwheels turned by Fairbanks Morse diesels bragging 760 hp. The Geo. T. Price, J.J. Hennen and others of the propeller type were making their mark in the industry, and bigger things were in the works.

In 1929, the Standard Unit Navigation Company (SUNCO) took delivery of a very special type of craft constructed by the Nashville Bridge Company of Nashville, Tenn. SUNCO, formed by Carl J. Baer, originally of Gallipolis, Ohio, was the forerunner of the Mississippi Valley Barge Line Company (later simply the Valley Line), which in 1930 would build four large steam propeller towboats, the Indiana and Louisiana constructed by Ward at Charleston, W.Va., and the Ohio and Tennessee built by Dravo at Neville Island, Pa. These boats looked virtually identical, and over the years all eventually would be converted to diesel power. SUNCO built 49 barges with dimensions of 100 by 21 feet intended for operation on smaller rivers. In 1928, SUNCO had a small 48.5- by 13-foot towboat built by Nashville Bridge that was named SUNCO A-3.

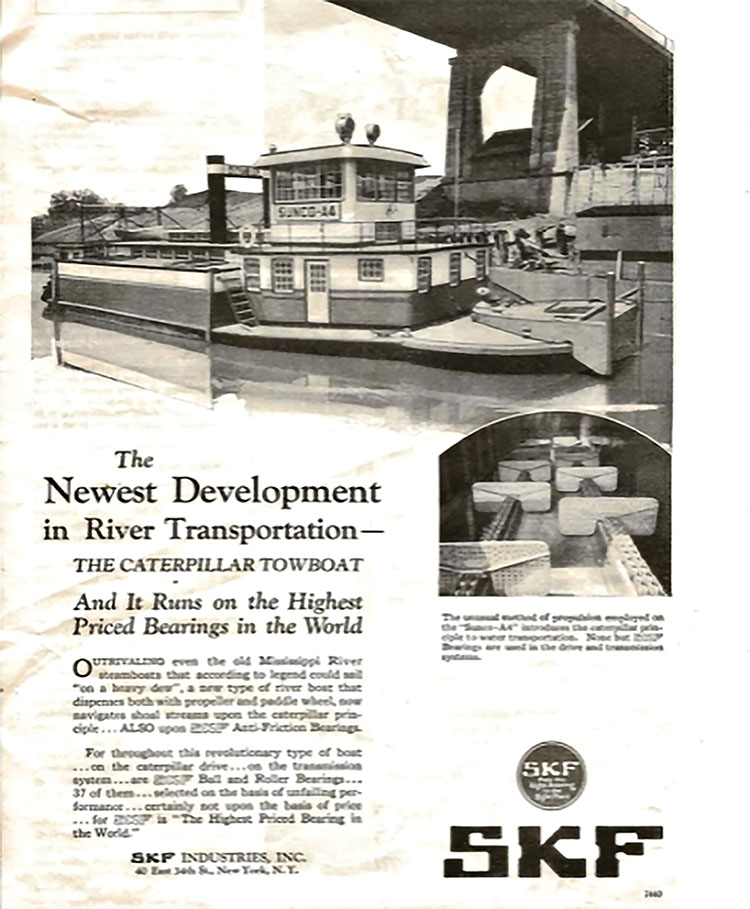

The special craft built for them in 1929 was much larger. The size as given for its first many years of existence was 93 by 18 feet. However, photos show the width as obviously much more than 18 feet, and in later years it was given as 33 feet. The name of the new boat was SUNCO A-4, and its propulsion system was quite peculiar. It had a pair of 100 hp. Winton diesels, each driving a Westinghouse generator supplying power to 80 hp. motors of 270 volts DC. These motors drove a type of sidewheel mounted on each side, somewhat resembling a caterpillar-type bulldozer tread, but with staggered paddles attached to continuous chains.

The A-4 had pilothouse control that allowed each side to work independently, and one side could back while the other came ahead. There were no rudders provided for steering, but the towing knees were attached to a frame on rollers that moved side to side by means of air motors, and steering was accomplished by moving this frame one way or the other.

The design of this vessel, described as a radical experiment, is generally attributed to Carl Francis Jeffries, another Gallipolis native and the chief engineer for SUNCO. Photos of the boat under way with some of the small barges, and presumably under trials while new at Nashville, show a noticeable wake thrown by the tow. But over the long run, did this “radical experiment” work? Unfortunately, no.

After all these years, details of its operations while new, and in the following years, are somewhat sketchy. The August 16,1930, edition of The Waterways Journal carried a news piece authored by Capt. Jesse P. Hughes and headlined “Huntington Glimpses a Caterpillar Towboat.” The piece indicated that the SUNCO A-4 had stopped at Huntington, W.Va., while enroute to Pittsburgh. It gave details on the boat, including that it had been designed by Carl Jeffries, at that time a Huntington resident. In this same issue, the “Gallipolis Gossip” column by Frank Sibley states that the boat arrived there “with a very heavy tow consisting of empty steel barges and the General Contracting Company fleet of dredges,” and that it was making “about 4 miles per hour in pool water.” The column also said that the boat was the first caterpillar electric-driven boat ever to ascend the Ohio and was one of only four such boats in the world. The column went on to mention that Capt. L.H. Middleton was master, Virgil Maroney was chief engineer and that the boat and tow had “stuck for several hours” on Kanawha Bar after departing Gallipolis but had got off.

The following week, the Gallipolis column of The Waterways Journal of August 21, 1930, again made mention of the SUNCO A-4 and said that “Capt. Moten Stanley piloted the Sunco and big fleet up the Ohio, having been sent for at Point Pleasant (W.Va.) to join the boat at Pomeroy (Ohio). Wind and low water have caused the Sunco, first caterpillar-designed craft driven by electricity, trouble at some places.” In this same issue, J. Mack Gamble mentioned the boat in his Upper Ohio news column as having passed up by Clarington, Ohio, and also said that the SUNCO A-3 was in tow with it, with both boats in operation. Gamble went on to state that “The Sunco A-4 makes an excellent appearance, and it was commented that she seemed to have very good power.”

Harbor Point

I don’t know what happened with the boat from this point to the 1945 initial issue of the Inland River Record. The IRR lists it as a sidewheel towboat of 200 hp., now named Harbor Point and owned by Waterways Transportation, St. Louis. By this point the caterpillar tread-type sidewheels had been removed and traditional circular sidewheels placed. It may have done somewhat better with these wheels, but the 1946 IRR lists it in the “Off the Record” section, showing it as having been dismantled at St. Louis in 1945.

By 1948, it is listed as the Edwin F, owned by Mid-Continent Barge Line, St. Louis. The listing states that it had been rebuilt in 1946 and now had three Murray & Tregurtha Harbormaster units for propulsion. These units were like large outboard motors, mounted at the stern, and the lower portion containing the prop could turn 360 degrees. In this application, the two outer units were powered with GM 6 cylinder diesels of 165 hp. each, and the center unit with a Cat 8 cylinder diesel of 140 hp. It is interesting that the listing shows the center unit having two props, “one pushing and one pulling.”

In 1948, with the original system of wicket dams in place, the Ohio River levels at Catlettsburg, Ky., and Kenova, W.Va., fluctuated greatly. There were no harbor services in place then, and Ashland Oil & Refining Company experienced great difficulty in keeping their various fleets in the area floating freely.

Those in the marine department were looking for a small boat to use in keeping the fleets off the banks. As the story was told, and confirmed to me later by Robert L. Gray, long-time engineering chief Ben Tracy was tending to some Ashland Oil equipment at the Mound City (Ill.) shipyard. He called Gray, then marine superintendent at the company, and told him, “Bob, I think I found us a boat.” The Harbor Point (that name was back on it) was laying at Mound City, virtually dismantled and for sale. Tracy told Gray that the price on it was $1,000. Gray told him to see if they would take $800. The deal was made, and the boat was sent to Catlettsburg.

Under Ashland ownership, the boat was initially outfitted with two M&T Harbormaster units powered with GM diesels of 230 hp. Pilots who tried to handle the boat would walk away in disgust. Joe Bauer had worked at an Ashland filling station prior to World War II and was now a veteran who had spent two years in a German prisoner of war camp. He had been serving as a timekeeper at the Catlettsburg Repair Terminal when the last of several pilots had given up trying to operate the boat, and he offered to try. He would spend the next 35 years as its master, and in later years was joined by Capt. Paul Ball as relief master and Capt. Larry Williams as pilot. Capt. Joe once told me, “When I retire, I don’t want a gold watch. I just want them to give me the Harbor Point—we grew up together.”

The Harbor Point was a busy fixture in the Catlettsburg area and on the Big Sandy River up to the company refinery. By 1964, a third M&T unit was added, and it now totaled 395 hp. In 1975, it was repowered with GM 12-V71 diesels and now boasted 1,020 hp. Shortly after this repower, it went through a drydocking and rebuilding program that included raising the pilothouse a few feet. As previously mentioned, these M&T units were somewhat like large outboards, and they could be raised up out of the water, which was convenient in order to remove lines and change props when necessary. As the units became older,they required more frequent repair, and a mechanic at the Ashland Oil motor shop once speculated that it was a full-time job for three mechanics just to keep it operational. Many who later rose to higher rank within the Ashland organization started as deckhands on the Harbor Point.

In 1983, Ashland Oil took delivery of a new harbor boat named Kyova, and the Harbor Point was sold to Merdie Boggs & Sons, who renamed it City of Catlettsburg. Under Boggs ownership it was not utilized much, and in 1991 it sank while moored at their landing. The vessel was raised by River Salvage of Pittsburgh and sold to them as part of the deal. River Salvage dismantled it in 1992. The pilothouse was on a landing barge at the Shenango works at the upper end of Neville Island, Pa., for a time, and I later saw it sitting on the bank at Glenwillard, Pa. I don’t know what became of it from there.

The “radical experiment,” as the SUNCO A-4 had been described in 1929, remained somewhat radical and unusual throughout its 63-year existence. It served Ashland Oil faithfully and successfully for 35 years, and the Murray & Tregurtha Harbormaster units operated somewhat like the modern Z-drive technology does today. In that sense the old Harbor Point was Z-drive years before Z-drive was cool.

Caption for top photo: The SUNCO A-4 as a sidewheel towboat. (Capt. Ben Gilbert photo from Dan Owen/Boat Photo Museum)

(The author wishes to thank Barry Griffith for his assistance in gathering the photographs for this story.)