The last of three Kentucky riverport freight summits designed to improve communication between the state’s riverport officials and economic developers and to better understand the 11 public ports’ resources, needs and potential for investment to bring about more jobs took place online August 31-September 2.

The Kentucky Transportation Cabinet hosted the Statewide Strategy for Kentucky Riverport Investment summit as part of its Kentucky Riverports, Highway and Rail Freight Study, which has been ongoing since early 2020.

In a recorded welcome to participants, Transportation Secretary Jim Gray said the study is important in part because it gives the state a focus for how to most effectively invest in its riverports.

Mikael Pelfrey, director of the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet’s division of planning, said the summit took place at a critical point in the study as it is a last opportunity to engage stakeholders. Both a final report and a marketing toolkit are due to be delivered to each riverport, along with state officials, in October. Pelfrey noted that the last study, in 2008, led to the creation of the Kentucky Water Transportation Advisory Board and dedicated annual grant money for riverport funding.

“The difference between this summit and the other summits we’ve had in the past is that we believe we have built a good understanding of the economy, where it’s headed,” said Chandler Duncan, project manager for contractor Metro Analytics. “We believe that we’ve answered the question about what’s moving in the riverports, about where it is coming from, where it is going, what our commodities are. Now we have a good foundation to start talking about what we can invest in riverports. What can we achieve with that investment? Where can that investment come from? And how can we create business opportunities for the riverports and the rest of Kentucky so that when we make that investment we make it wisely. And we’re very interested in all of the heads coming together at this summit to get that information out there and to learn from even the things that have changed during the course of our study to do that, so that we can get all of that really great insight and information into a living product that will go out to this community this fall that everybody will be able to go out in the world with.”

Duncan noted that Kentucky’s waterways carry more than 80 million tons of freight each year, worth more than $18 billion.

Study research has determined that logistics, aluminum and other sectors show potential for increased use of waterborne commerce, he said.

Currently, five commodities comprise 89 percent of today’s Kentucky riverport market. They are petroleum and crude (29 percent), coal (19 percent), aggregate (16 percent), grains (15 percent) and chemicals (10 percent). Growth in oils, plastics, warehouse/distribution and grain are expected, but that is also expected to be offset by reductions in coal transportation.

Additional investment in the state’s riverports is needed, however, with Kentucky’s annual $500,000 port funding lagging behind that of other states, Duncan said.

The study has included two rounds of port visits that have revealed needs for preservation and new investment opportunities, he said. Additionally, he said, input from the first two summits and from interviews have shown strong interest in market capture and business intelligence.

Duncan said key points of the third summit were information on how to exploit opportunities for new funding, prioritize highest market opportunities, relate port investment to market capture, provide ongoing access to data/market intelligence resources used in the study and, finally, to use the information gathered to produce a final report and a marketing toolkit, including promotional materials and resources, executive briefing materials and implementation resources.

“We’re looking into the details of it and how that will impact opportunities for state transportation cabinets and DOTs to fund infrastructure at all modal levels and what is the best strategy and scenario that the ports could put forward either individually or collectively to fund projects and investments that would help them and their customers produce new business for the state, new opportunities and jobs for their communities and also to be able to provide additional revenue streams for those communities,” said Jimmy McDonald, deputy project manager for Metro Analytics.

Connecting Ports to Global And Domestic Trade

Ken Eriksen, senior vice president–head of client advisory and development, energy and transportation and policy for IHS Markit, moderated a panel that was supposed to be a conversation with inland barge operators for one session.

Unfortunately, as it came about roughly 48 hours after Hurricane Ida slammed into the coast of southern Louisiana, only one barge company representative was available to speak at the virtual session. Steve Alley is vice president of sales for Ingram Barge Company of Nashville, Tenn. He also is a founding member and continues to serve on the Kentucky Water Transportation Advisory Board and has 38 years of experience in the industry.

Alley updated participants on the effects of Hurricane Ida and how inland barge companies were responding to the aftermath. He also focused his comments on how waterborne commerce in Kentucky connects with commerce elsewhere in the country. For example, before the hurricane, a lot of stone coming out of Kentucky quarries was being transported down to the Gulf of Mexico, he said.

“We had rigs that were around Calvert City where we were loading rocks to go to the Gulf,” he said. “All that is stopped right now.”

Like elsewhere around the country, barge companies doing business in Kentucky are facing employee shortages, Alley said.

Ingram has hundreds of employees who live and work in the Paducah area alone, he said. The company’s largest fleeting area is in Columbus, on the Mississippi River in the far western part of the state. Ingram also has operations in Silver Grove, part of the greater Cincinnati area, and a sales office in Louisville.

The shortage of workers has led to Ingram incentivizing deckhands to stay on board.

“It’s difficult to hire right now because you can go to work in an air-conditioned factory making 25 bucks an hour, but in our industry it’s tough work. You’re out working on boats and barges. You’re in the heat, out in the elements, and you’re in the snow. The thing is if you come to work for our industry, you work six months, 30 [days] on and 30 off, and if you like that lifestyle and can get used to that lifestyle it’s a great career.”

Along with that are opportunities for employees to work their way up in the industry, he said.

People outside the state often don’t realize that Kentucky has the fourth largest waterway attachment in the nation, with 1,590 miles of waterways that touch the state.

“There is a huge amount of business that takes place in our ports, and we should be grateful that Kentucky has 11 public ports,” Alley said, noting that most states don’t have so many.

“The impact of the waterways on the state is massive, and that’s why so many companies have operating headquarters in the state of Kentucky, in the Paducah area, because that’s where it takes place,” Alley said.

Alley highlighted the importance of investing in infrastructure as key to those jobs.

“The first thing is we have to keep the locks and dams operational,” he said.

Kentucky does face some challenges along its waterways with decreasing coal volumes, but it is well positioned geographically for potential growth in part because of all the industry already in Kentucky and because of the many other products moving on the waterway system through the state.

“The public terminals have an advantage over other states in that we have an economic development team in Frankfort, and we have the ports in the state of Kentucky,” Alley said. “Those two working together, I believe, can do some amazing things for this state.”

It is important to make sure that the economic development team is in constant communication with port directors and sharing information about potential clients in a confidential way, he said.

If they do so, “I think the growth opportunity for the state as compared to other states around us is untouchable,” he said.

Additionally, he said, it will be important to think creatively, even with small shipments that have the potential to grow. An example he gave is a new project in which paper waste is being shipped by barge from Kentucky, then being offloaded by truck and sent to an Ohio company to be used to make cardboard boxes for online sellers such as Amazon.

“This industry won’t look the same 20 years from now,” Alley said. “We won’t just be moving bulk cargo from A to B. And we have the ports set up in the state of Kentucky that can handle it. That’s rare.”

Kentucky needs to do a better job in marketing its waterborne capabilities, Alley said.

“I don’t believe the world knows what Kentucky has to offer from a port standpoint,” he said. “They don’t realize we have these 11 facilities available for them. And I don’t blame anybody for that. It’s something that has developed over the last three to seven years as businesses have come to the state or come through the state to ship their products in and out all over the world. They don’t know that we exist. They just know they need to find a dock.”

Alley said Kentucky’s public ports are competitive when compared with other states. “And they are modern,” he said. “And we have some very intelligent port directors, smart people who have been doing this a while, but they’re running this day to day. We’ve got to get to the global level and let folks know that this little state in the middle of the country has this phenomenal system set up.”

One need the state has is to better improve how those 11 separate ports work together. “They need to run like 11 different pieces of a profit center,” Alley said. “Get those groups talking on a regular basis, sharing what they’re doing, and come up with a marketing plan, and present it to the industry. The industry needs to know, and the world needs to know.”

Anticipating The Evolution Of Freight Commodities

In a session titled “Anticipating the Evolution of Freight Commodities: A Conversation With Corn, Soy And Aluminum Representatives,” all the speakers stressed the importance of less expensive, more efficient barge transportation as key to their businesses.

The session was moderated by Tim Hughes, senior trade adviser for commissioner of the Kentucky Department of Agriculture.

Adam Andrews of the Kentucky Corn Growers’ Association said Kentucky farmers produce about 225 million bushels of corn a year, less than half of which is exported because of the state’s robust livestock industry, its bourbon industry and one ethanol plant in Hopkinsville that produces about 60 million gallons of ethanol using 25 million bushels of corn annually.

“Before the river, we’re fortunate to have a large domestic portfolio of domestic customers,” Andrews said.

Of the corn that is exported, he noted that a lot of it is trucked across to Illinois, Indiana or Tennessee and barged from there because large grain elevators are mostly along the river in those neighboring states.

“I see that as a great opportunity for us to build infrastructure on our side of the river,” he said. “There are multiple benefits of that.”

Andrews said it is also impossible to talk about corn exports without discussing the impact of China, which has a hog herd six times larger than that of the United States. To rebuild that herd following the global pandemic, China has already imported four times more grain in 2021 than it did in 2020, and most of that is coming from the United States, he said.

Jonathan Miller of the Soy Transportation Coalition asked the question, “So why does the farmer care about riverports?” before answering it himself. “We need access to markets, and 95 percent of the world lives outside of the United States.”

American competitiveness with South America for grain exports is dependent upon our inland river system, he said.

“Maybe the biggest advantage we have over South America is that for a little under $2 a bushel we can get grain from Chicago or Kentucky to Shanghai compared to over $3 from Brazil. Our profit is made possible by our waterways, locks, dams, tugboats and even the mooring dolphins that we need to be thinking about as bus stops for barges out there, but all of this requires enough competition out there on the waterways to pass along some of that savings to us.”

He urged participants to think back to May 11, when a crack in the Hernando de Soto bridge in Memphis, Tenn., led to barge traffic on the Mississippi River being halted for three days. It immediately cut the local basis—the difference between the Chicago Board of Trade price of grain and the price the farmer receives at the local grain elevator—by 10 cents, he said.

“It was probably the beginning of the end of high prices for this cycle of grains before the harvest,” Miller said.

Additionally, he said, riverports are important to increase competition and improve the local basis paid for grain.

“Most importantly, we need competition to force our local facilities to update for faster unload times,” Miller said.

He showed a photo of a line of farmers in tractor trailers lined up at a grain elevator during harvest time to unload their corn, saying it takes all day long.

“You just don’t have time for that,” he said. “We have very little help and can find very little help.”

Ultimately, he said, those who farm closer to the river get a better price for their soybeans than those who live farther away from it because it costs less to get their crop to market.

“Less fuel and lower cost per ton, river transportation is ideal for grains, so it makes a perfect partner for farms, especially with the expansion of ethanol,” Miller said.

Additionally, he said, it makes a difference in the prices farmers pay for fertilizer, which can be significant. Personally, he said, where he farms in McLean County, he spreads 500 pounds of fertilizer on each acre of corn crop.

Finally, Mike Keown of Commonwealth Rolled Products, a producer of rolled aluminum in Lewisport, noted that Owensboro, Ky., is becoming the epicenter of the aluminum industry, in part because of the location of smelters and rolling mills that shape raw aluminum into finished plates, sheets and coils.

Commonwealth Rolled Products recently spent $600 million to expand and modernize its automotive body sheet and industrial products facility and expects to spend $150 million to $200 million in the coming years.

“We see nothing but positive growth in North America,” he said, driven in part by aluminum content in vehicles projected to grow from an average of 460 pounds to 515 pounds per vehicle between now and 2026.

Currently, Keown said, about 60 percent of the raw material used by Commonwealth is coming in from the riverport system, largely from Canada, Russia and the Middle East. Another 25 to 30 percent comes in via rail, but much of that was offloaded at a port before being delivered. No current product is currently shipped by barge. Most goes out by truck, with a limited amount via rail.

Riverport Investment Strategies

In a session focused on how to invest in the state’s riverports, Duncan and Noel Cormeaux, also of Metro Analytics, said interviews with riverport directors showed more than $195 million in projected needs at the state’s riverports over the next five years.

In looking at the needs on a systemic basis, Metro Analytics broke the needs into three categories: those to preserve business, those to optimize port efficiency and, finally, strategic investments that preserve or capture market position, attract modal share or reroute additional tonnage to use Kentucky riverports at a lower cost or with improved access compared to competing ports.

That last category accounted for roughly half of the riverports’ projected needs. This type of investment often costs more, Cormeaux said, but it also holds potential for increased return on investment.

“You’re spending more money, but you’re yielding greater benefits,” he said.

Examples of that last type of investment included construction of waterfront infrastructure as well as land acquisition and adding rail and highway access, new equipment and warehousing.

In analyzing potential investments, Metro Analytics also considered particular commodities and cargo types, including potential emerging new markets.

“We need to take what we have learned in the last two summits we have had and what we have learned in all the economic intelligence and the forecasting that we have gotten and understand what that means for port investment,” Duncan said. “We’ve talked about things like that our coal market is not going to be what it was. There are emerging opportunities. There are new commodities. There are new markets that could come up, but that means we have to invest something to make ourselves available for those markets. It also means that we’re probably going to have to capture some different markets. Technology is changing, and the same things we’ve always preserved and used in the past may not be adequate for our future needs. Some of our assets are just getting older, and our competitors, other states as well as other industries, are moving forward. What does it mean for us to do that?”

Metro Analytics also looked at whether improvements were on-site or off-site as well as current and new commodity origins and destinations. Those origins and destinations included looking at potential projects partnering with out-of-state ports, including Marine Highway projects and potential container-on-barge projects.

Looking at such projects on a systemic basis is important, Duncan said, because while one project may seem insignificant to an individual port’s daily business, it could be part of a larger gain for the state as a whole.

Individual recommendations for the ports and potential sources of federal grants and other funding will be included as part of the final report.

Capital Improvement Needs

McDonald led a session on available funding programs as determined by MetroAnalytics. He then opened the presentation into a discussion with Tim Cahill, executive director of the Paducah-McCracken County Riverport Authority.

Kentucky’s Riverport Improvement Program grants provide $500,000 annually, with a required 50 percent match. The majority of allocations are to access related highway, rail or waterway projects, McDonald said. In total, the program has provided $4.9 million to riverport projects.

“This has been the only program that is funding these programs specifically for the ports,” McDonald said.

However, he noted some challenges with the program, including that the legislation funding the grant program lacks carryover authority and that ports must use state-prequalified contractors lacking maritime expertise for the work rather than using a contractor they have a relationship with already or using their own employees to provide in-kind services. Additionally, the funds are a line item in the general revenue budget and can be vetoed by the governor. Finally, ports don’t always have the money in a 50/50 match program to go after larger projects through the program.

In looking at “peer states,” including surrounding states and Florida, MetroAnalytics found Ohio is providing $7.5 million in state budget dedicated funds annually, Missouri $600,000, Virginia $42 million and Florida $76 million.

In looking at state port grant programs, Ohio provides $23 million annually, Illinois $150 million annually, Missouri $9.4 million annually, Virginia $5 million annually and Florida $44 million annually, although some of those states have much larger blue-water ports.

Federal programs include $906 million in 2021 INFRA grants, $100 million for FEMA’s Port Security Grant program, $1 billion in the U.S. Department of Transportation’s RAISE grant program and $230 million in the U.S. Maritime Administration’s Port Infrastructure Development program, among others.

The current federal infrastructure bill under consideration by the House of Representatives currently includes $17 billion for ports nationwide, McDonald said. He added that the White House estimates Kentucky to receive $6.1 billion for transportation infrastructure. The same estimate shows waterways transportation funding for Kentucky at $647 million.

McDonald added that even if federal grant money is not available, “very good, low-interest government loans” exist.

Cahill talked about the challenges that port directors face. For the Paducah port, he said, that includes having only 48 acres of property, of which only 12 are developable. From that standpoint, he said, it is important to cultivate relationships to assist current customers as well as to create opportunity through transshipping or other strategies wherever they may be in the county, inside or outside of the port.

He echoed the sentiment that Kentucky’s grant funding is limited, “so you pick and choose what you go after,” especially when it requires a 50 percent match.

Additionally, he said, the port’s equipment is old, as is the case in many of the other state ports, and it will be important to modernize the equipment to prevent failure in the future that would affect customers.

The port is currently seeking a federal grant for rebuilding its bulk yard, with much of the required local match pledged by existing customers.

Cahill also talked about the importance of working together with other port directors and with the state in economic development and marketing efforts, saying that the study and accompanying summits were an important step in continuing those efforts. He would like to see those conversations continue in regularly scheduled conferences, annually or biennially.

Additionally, he said, increased funding for port improvements and modernizations will be increasingly important with surrounding states investing in ports on the other side of the river from Kentucky ports. In Paducah, he said, that includes ports being developed in Metropolis and Cairo, both in Illinois.

He also shared some of his successes, including having conversations with grant providers to make sure potential projects met the qualifications and hiring a local engineering firm with experience in grant writing to assist in its grant application.

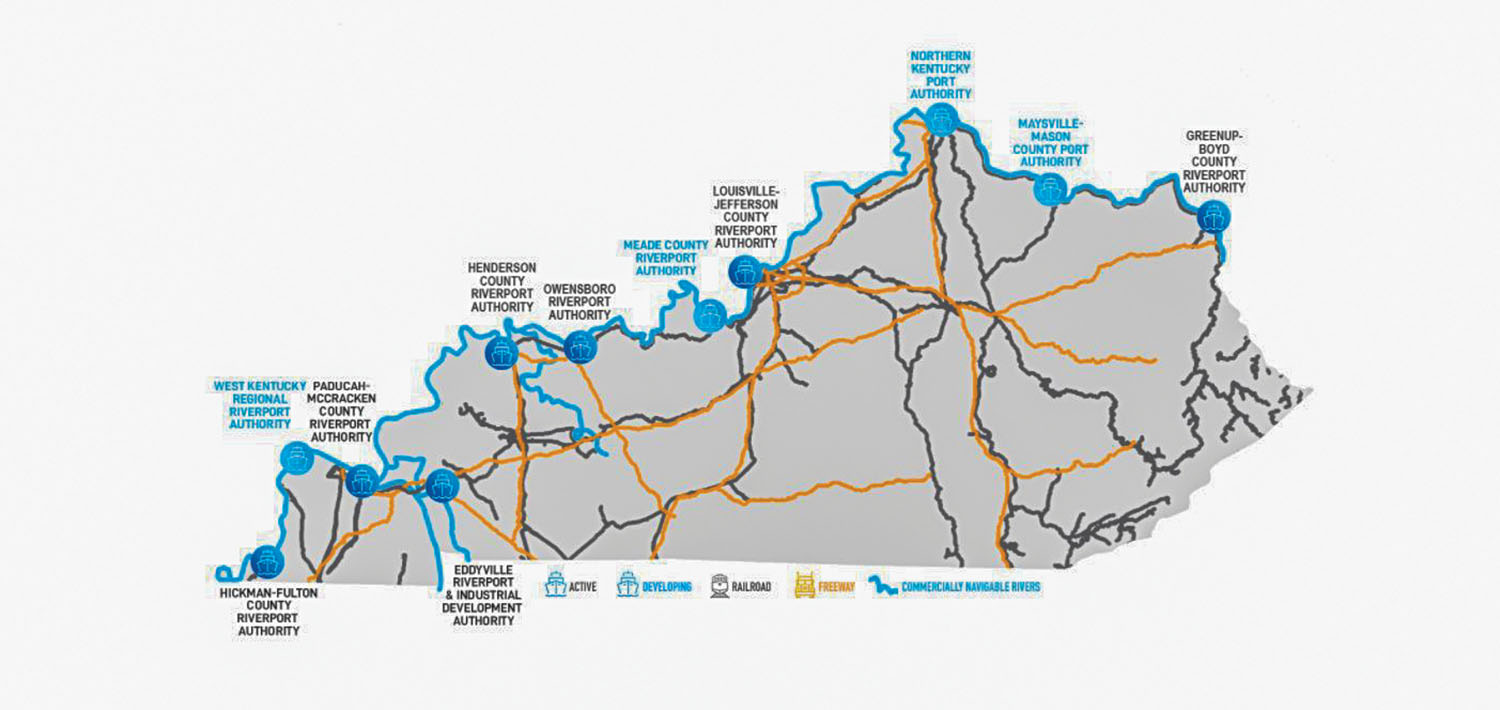

Caption for graphic: A graphic shows the location of Kentucky’s 11 public riverports. The Kentucky Riverports, Highway and Freight Rail Study has included three summits focused on the riverports to improve communication with state economic development officials and provide better understanding of the ports’ resources as well as to develop an investment strategy. (graphic courtesy of the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet)