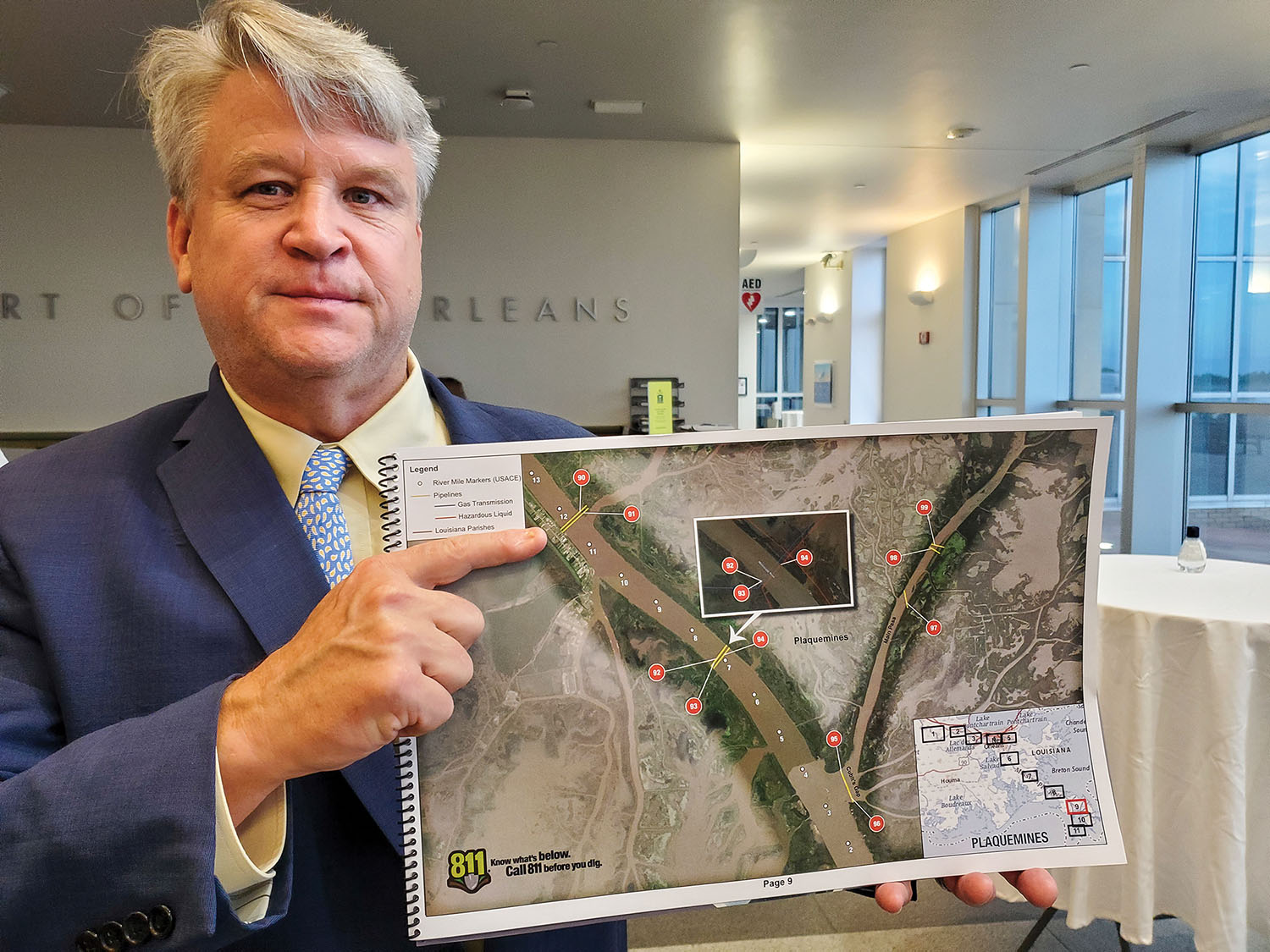

Coastal and Marine Operators (CAMO) released its Lower Mississippi River Pipeline Identification Guide at a meeting held August 18 at the Port of New Orleans. The publication identifies regulated gas and hazardous liquid pipeline crossings from Mile 167.9 above Head of Passes, through below Head of Passes.

CAMO largely focuses on the interface between navigable waters with pipelines and other underwater infrastructure such as power cables. The guide shows the mile location of pipelines, latitude and longitude, name of owner/operator, pipeline system name, product in pipeline and a 24/7 emergency contact phone number.

More than 60 industry and government partners were in attendance while an additional 40 partners participated via a Zoom videoconference call.

Subsidence of land, particularly in marshes and along navigable waterways, has led to explosions when a vessel strikes a pipeline. Most recently, four crewmen were killed in a fire and explosion in the Corpus Christi Ship Channel in August 2020 after a pipeline was punctured by a dredge.

Vessel strikes of pipelines are a low probability, but of high consequence, said Capt. Kelly Denning, deputy commander of Coast Guard Sector New Orleans.

Concerns About Location, Draft

Concern for pipelines’ exact location and depth below the mud line was one of the issues that was addressed during presentations. In shallow water, vessel propellers push water from under a vessel, causing a vessel to sit deeper in the water in a condition known as squat. This makes it important to know how deep a pipeline actually is below the mudline.

Sean Duffy, a member of CAMO’s Dredge and Pipeline Subcommittee, is the executive director of the Big River Coalition, a well-respected maritime trade and advocacy association that is credited with successfully promoting and securing funding to deepen the Mississippi River Ship Channel to 50 feet.

While river dredging has opened large sections of the Mississippi River to deeper drafts, Duffy said concern regarding four pipelines, two clusters of two pipelines each, with one pair transmitting natural gas, currently restricts deep-draft vessel traffic in the “Venice Corridor” near Mile 12 above Head of Passes and just upriver from the junction with the Baptiste Collette waterway.

Even though dredging has been completed through the Venice Corridor area, vessel traffic remains restricted to the prior maximum draft of 47 feet until accurate surveys can be provided for these pipelines, Duffy said.

Channel deepening in the first 30 miles of the ship channel was completed via mechanical dredge extraction on May 7, but allowing deeper vessel transits has remained on hold as questions about the pipelines in this corridor were uncovered, he added.

The second cluster of two pipelines are reported abandoned, and that data was provided by the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA). Bill Lowry, a PHMSA official from the Southwestern District in Houston, said his office oversees many of the Mississippi River pipeline crossings.

Lowry said in the past, when a company abandoned a pipeline, there was not always a requirement to report its location or abandonment to authorities. Announcement of a pipeline abandonment is now required, but PHMSA is not always made aware of the status.

He added that PHMSA is not a permitting agency and that pipeline permits did not always require abandonment notification.

Duffy said he learned of technology available to the military for locating unexploded ordinance that may be able to pinpoint pipelines’ location and depth below the mud line. That equipment will be in Mississippi in October, and if suitable for pipeline location identification, he said he will be trying to have it be made available to identify the depths of pipelines in the Venice Corridor.

If this technology can provide accurate pipeline depth information, it would also be critical to the deepening of the ship channel above New Orleans, where the Corps of Engineers is concerned about 14 additional pipeline crossings, Duffy continued.

He admitted being surprised that normal survey methods are often not able to locate pipelines or obstructions buried beneath hard sand.

Economic Impact

Lt. Eric Acosta, facility security officer at the Port of St. Bernard, noted vessel traffic on the Mississippi River is a huge contributor to the commerce of the country. He pointed to the cyberattack shutting down the Colonial Pipeline and said an incident involving a pipeline strike could shut down the Mississippi River and have as much, or more, of an economic impact than the recent cyberattack pipeline shutdown.

During high river conditions, Acosta said tows are not allowed to push against the bank while awaiting lock turns or dock space. He said his office has issued warnings via VHF radio to mariners pushing a tow against a bank in violation of the high river restrictions, and if the tow did not move quickly, Acosta said his office issued fines of up to $2,000.

Chris Accardo said the Corps of Engineers attempted to mark pipeline crossings along waterways, but during high river, floating logs were very destructive and knocked out many of the signs. Accardo now works in private industry as a consultant, but he was operations manager for the Corps’ Mississippi River operations before retiring.

A dredging operation in Tiger Pass below Venice, La., is being conducted by Crosby Dredging LLC of Golden Meadow, La. With 16 pipeline crossings in Tiger Pass, Joe Caldwell, Crosby’s general manager, called it a “poster child” for safety concerns in waterway dredging. Dredgers are normally required to maintain a 50-foot buffer from known pipelines, but surveys of the pipeline locations do not always give enough information, he said.

Call Before Digging

Brent Saltzman of LA One Call gave an overview of how the marine 811 call system works. Before digging on land or in waterways, the law requires a call to have pipeline and utility companies mark their lines.

On land, the owners are required to mark pipelines and power cables within three working days, but in the marine environment, the time can be negotiated because of the difficulty of access and equipment availability, Saltzman said.

Ed Landgraf, chairman of CAMO, said the Mississippi River pipeline guide is available through CAMO’s website at www.camogroup.org.

Funding for the publication was provided through a technical assistance grant awarded to the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation, doing business as Pontchartrain Conservancy, and from the U.S. Department of Transportation, Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. In addition, contributions were made by CAMO members, Landgraf said.

Caption for photo: Sean Duffy with the Lower Mississippi River Pipeline Identification Guide. (Photo by Richard Eberhardt)