Two pieces of property acquired by the former Pitmarine Corporation owner have historic ties to the rivers and the Pittsburgh area.

The properties were listed for sale last month following the death of Capt. Graydon “Bub” Crain in July 2020 at age 86.

Crain, of Cranberry Township, Pa., was one of the founders of C&C Marine, which is now Campbell Transportation Company Inc. He was the middle son of Mason “Spike” Crain, who began Crain Bros. Inc., a well-known marine construction, towing and salvage firm. Crain left Crain Bros. in 1969 to partner with Tom Campbell to launch C&C Marine. He eventually started Pitmarine as his own venture and continued to operate it until his retirement several years ago.

Ashley Anttonelli, Crain’s granddaughter, remembers him fondly.

“There’s an old saying that rivermen are story-tellers, and that’s exactly what he was,” she said.

She recalled that for his 60th birthday, the family rented out one of the Gateway Clipper fleet boats for an evening river cruise.

“That’s all he did for 3-4 hours while we were out on that ride, just tell stories and jokes,” she said.

It wasn’t all play, though. She said her “Poppy” taught her and her sister about having a strong work ethic, getting up at 5 a.m. and never stopping for a lunch break. “You don’t quit when the sun goes down,” he would tell them. “You quit when it’s quitting time or the job gets done.”

Crain never went to high school or college, so people are amazed at all he was able to accomplish, from founding and building businesses to fabricating his own 100-foot sternwheeler, the Betty Lou.

“I saw him build that from a barge,” Anttonelli said. “Every single bit of it he built. Most people couldn’t believe that he didn’t have an engineering education.”

Crain even sought and obtained a patent for a “tri-tie” mooring structure he later sold for industry use.

“He was working on the river since he was 10 or 11 years old, assisting building bridge piers for some of these outfits back when he was younger, and ended up very successful,” Anttonelli said. “He owned a marine outfit and was president of C&C for a while and then ran Crain Bros. and then started his own company, Pitmarine, at the age of 34. Through all of those years he acquired some very interesting assets.”

Glass Plate Negatives and Pittsburgh City Photographer collections)

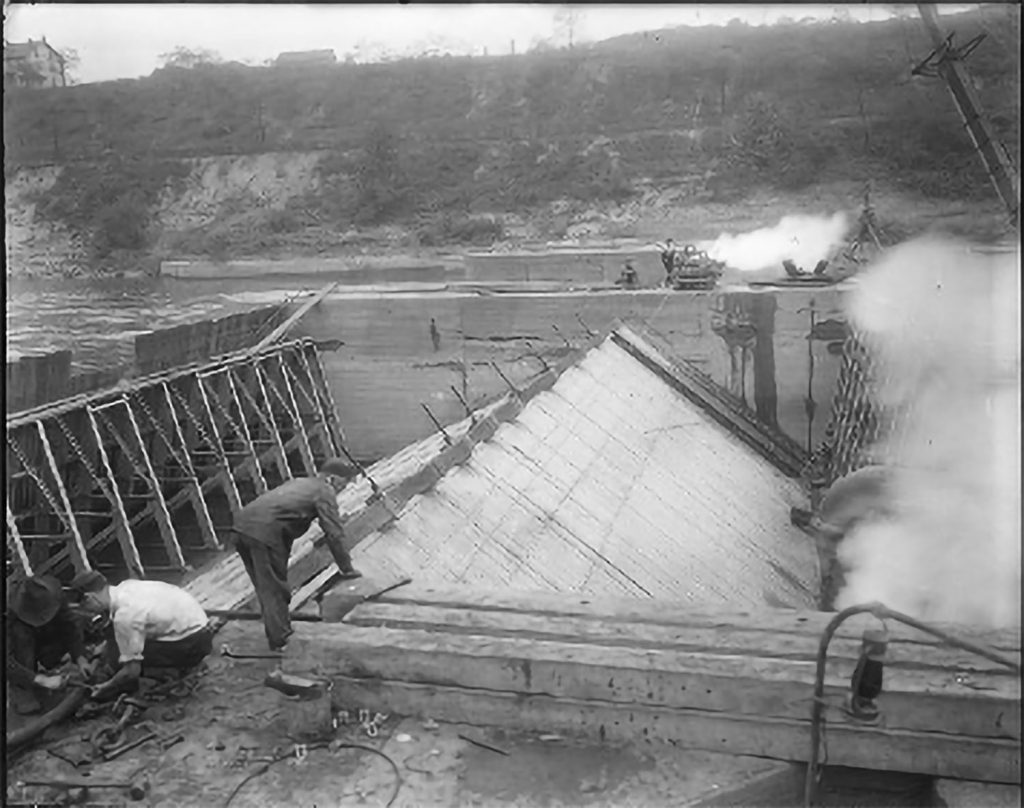

One of those assets was 17 acres along the Ohio River with 1,180 feet of river frontage at Mile 36.5. It includes barges filled with sand and gravel stacked 11 feet high to form a wall on top of what remains of the former Lock 7. Photographs maintained by the website Historic Pittsburgh, hosted by the University of Pittsburgh Library System, show the lock and dam under construction from 1911 to 1913. The photos are listed as originally coming from the Pittsburgh Engineer District’s glass plate negatives collection. Dam 7 was replaced by the New Cumberland Dam in the 1950s.

A former lockhouse is still on the property, although in dilapidated condition. It was previously used for storage, said A.J. Pantoni, director of industrial brokerage for Hanna Langholz Wilson Ellis of Pittsburgh. Pantoni was researching the properties for sales purposes and became fascinated by their histories.

The site also includes fleeting for four jumbo barges. It was most recently used by Pitmarine for barge fleeting before operations ceased about two years ago, Pantoni said.

Glass Plate Negatives and Pittsburgh City Photographer collections)

Anttonelli said her grandfather came by the property as part of a trade for other property he owned along the Ohio in Beaver County. Permitting regulations made it difficult for him to develop that property as he wanted, so he traded for the Lock 7 property instead.

Anttonelli said she thinks the history of the lock appealed to him as well.

“He was such a history buff,” she said. “He loved encyclopedias and histories of the river.”

In cleaning out his home following his death, she said, family members came across old river maps and “probably two truckloads of books.”

The second piece of property Crain owned is frequently a topic of conversation for those visiting the Pittsburgh riverfront. It includes two stone piers sunken into the Monongahela River at Mile 0.4. The piers stick up about 90 feet in the air on either side of the river. Each pier is topped with several flagpoles, although they no longer fly any flags.

“The way I’ve described these is you’ve driven by these a million times,” Pantoni said. “You’ve seen them in aerial shots a million times.”

In more recent years, the piers were leased out to moor the Gateway Clipper fleet on both the north and south shores.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, plans called for the piers to support a bridge for the Skybus, a mode of mass transportation that was to carry passengers between the city’s airport and downtown areas. The service was never built. Someone received and asked permission to install flagpoles on the piers for a celebration of some sort but never removed the poles following it.

Crain bought the piers at an auction. Anttonelli said he had dropped her mother off at a women’s clothing boutique she owned in the late 1970s and early 1980s and went to the auction with a friend. When he saw how cheap the price was for the piers, he decided to bid and ended up the winner.

“He was very proud of these bridge piers,” Anttonelli said. “I don’t think he had any plans for them. He just thought it was a neat asset.”

She added, “He was born and raised in Pittsburgh and worked on the river his entire life. He had a lot of pride in the river, so I think owning a piece of it made him feel pretty proud.”

Although plenty of people in the Pittsburgh area are familiar with the piers, few likely know their history goes back about 120 years.

Glass Plate Negatives and Pittsburgh City Photographer collections)

The Brookline Connection, a Pittsburgh area history website with its own listing about the Wabash Pittsburgh Railway, notes that by 1900, more freight was shipped through Pittsburgh than any other city in the United States, including the port of New York. Railroad baron George Gould envisioned the railway as part of an intercontinental system to move freight from coast to coast. He did so with sizable financial backing when, on February 1, 1901, steel magnate Andrew Carnegie signed tonnage contracts for his operations with the Wabash, ensuring the railroad would receive a hefty portion of the Pittsburgh shipping market.

Plans were approved the next year to build the Wabash Bridge to carry the railway over the Monongahela River to a huge wooden train station being built downtown.

The work was not without obstacles, as owners of competing railroads brought lawsuits, even as construction continued. When Carnegie sold his steel company to J.P. Morgan, previously negotiated freight contracts were nullified. As a result, the railway wasn’t ever able to turn a profit. The railway also endured a disaster before it ever opened as the wooden interior of the Bigham Tunnel, through which the railway would run, caught fire and collapsed. It was later rebuilt as an open cut.

The biggest calamity was October 19, 1903, the day the final piece of the Wabash Bridge was to be set. Five I-beams weighing nearly 9 tons were being hoisted from a barge to the incomplete bridge structure when a rope snapped and the jib staffs in the crane gave way. “And with a rasping, grinding sound, the whole mass pitched forward, hurling the workmen down into the barge as if they had been shot from a catapult,” the Pittsburgh Gazette reported the next day. “Tons of iron went with them. The men in the barge were caught as if in the jaws of a trip-hammer. Under the great weight the barge capsized and some of the men who were not killed outright were pinned under the twisted beams and drowned. Some fell over 100 feet and struck on top of the wreckage, escaping with terrible injuries. A few men struck the water and were saved.”

Ten members of the crew were killed.

Finally, in February 1904, the bridge opened. The 14-million-pound span measured 812 feet. That made it the longest railroad bridge in the country and third longest in the world, a status it held until 1909, according to The Brookline Connection.

The Wabash Pittsburgh Railway’s string of bad luck continued, however. They included a smallpox epidemic among workers, strikes, riots and flooding. Finally, the financial panic of 1907 took the Gould family fortune. Within a year, George Gould was forced to sell off many of his railroad holdings. By 1908, the railway was bankrupt. In 1948, the Wabash Bridge was dismantled, leaving behind only the stone piers.

Caption for top photo: Today, all that is left of the Wabash Bridge are two 90-foot stone piers topped with flagpoles. They are sunk along both the northern and southern shores of the Monongahela River. (Photo courtesy of Hanna Langholz Wilson Ellis)