Work continues on the addition of a second chamber at Kentucky Lock, with completion of the downstream cofferdam contract sometime in February projected to temporarily ease navigation delays that have been common over the last several months.

The earliest possible completion date for the entire project, at the Kentucky Lake reservoir of the Tennessee River, is in 2025, said Don Getty, project manager for the Nashville Engineer District.

“That’s assuming everything goes well,” Getty said.

The Kentucky Lock project includes adding a new lock twice as long as the existing 600-foot-long lock at the dam to reduce the significant bottleneck caused by high Tennessee River traffic levels and the current lock’s size.

The Corps of Engineers has an 80 percent confidence level in completion no later than 2028. Both figures take into account expected periods of high water. Construction on the project began in 1998, and the total cost is expected to be $1.2 billion when completed, requiring an investment of $562 million above which have been received so far and have not yet been awarded as part of contracts and contingencies projected through the projected construction timetable.

Work at the Kentucky Lock in 2020 and into 2021 has focused primarily on two ongoing contracts: for the downstream cofferdam and for the lock chamber excavation.

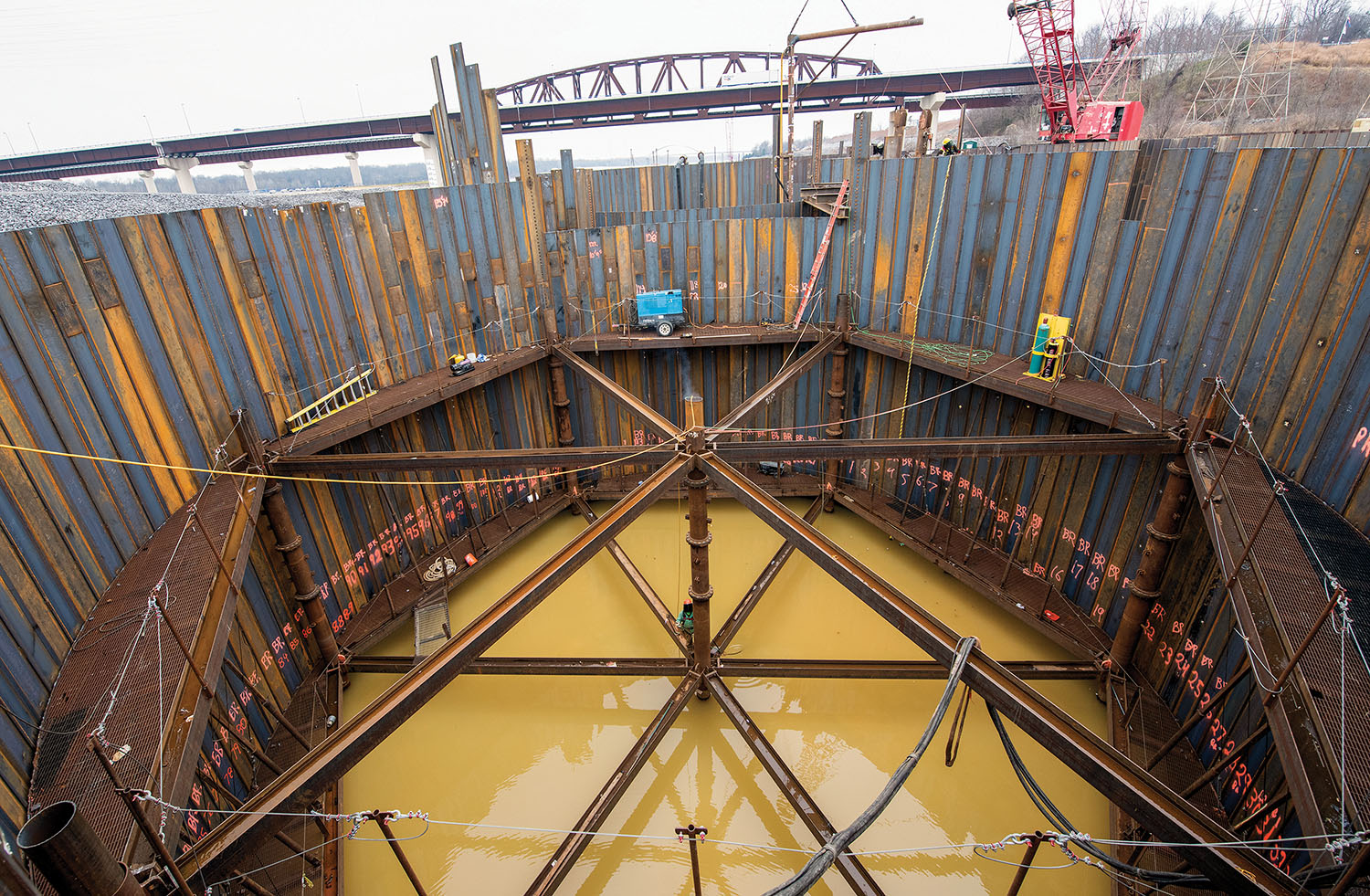

Cofferdam Construction

Downstream cofferdam construction has been the most problematic from a construction standpoint due to high water over the last two years, Getty said.

On February 2, 2020, the contractor, Johnson Brothers, used a gantry crane to lift in the last of 10 concrete shells lowered to the prepared bed. The last one weighed 1.3 million pounds, Getty said. The shells form part of both the cofferdam wall and the new permanent lock wall. The first had been set August 6, 2018. The contract has been in place since 2016.

“This type of in-the-wet construction has only been attempted at this one project that we’re aware of,” he said. “It’s turned out to be very successful. We refined the techniques as we went, and we even adapted to set these shells at higher river levels than we anticipated and designed for to accommodate all this high water the last two years.”

Because of its location, the project is easily affected by the Ohio River and Mississippi River levels above and below the dam as well as on the connected Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, but even rainfall as far away as Montana has some effect, Getty said.

Once crews completed installation of the concrete shells, they filled them with tremie concrete under water, placed through a pipe to the bottom of the shell. Once the concrete cured, crews sealed the shells, then cast an additional 24 feet of concrete in place on top of them in the dry, raising the level of the future lock wall to about 70 feet above the streambed. Despite setting the last shell February 2, water did not recede enough to allow the beginning of placement of the cast concrete on top of the last five shells until June 4. The final cast concrete was placed December 5.

“That was a huge milestone for this project,” Getty said.

Four traditional sheet pile cells are also part of the cofferdam contract. Two have been finished.

“We’re making tremendous progress on the last two of those four shells,” Getty said.

Lock Chamber Excavation

Progress continues to be made on the lock excavation contract, which began in September 2018, as well.

“That’s excavating out the soil and the rock necessary for us to start placing concrete for the remainder of the lock,” Getty said.

In essence, contractors have built the upstream one-third of the new lock and still have the bottom two-thirds to go.

Part of that work involves putting in large strand anchors that stabilize existing lock walls that will be part of the cofferdam. That requires crews to drill deep holes, some as much as 150 feet deep, through the concrete and into the rock. These are filled with bundles of steel cables that are grouted into the rock before a jack adds a million pounds or more of tension.

“This puts compression on the lock wall and holds it in place,” Getty said.

The excavation contract, which was awarded to Heeter Geotechnical Construction, also involves moving soil and rock. Most of the soil is already gone, Getty said. The rock must be blasted and removed a little at a time.

One of the next major steps in the lock excavation contract will involve dewatering the area to prepare for finishing the lower portions of the lock excavation.

“That will probably happen late this spring or early this summer,” Getty said.

The lock excavation contract is scheduled to finish in the first part of 2022.

Downstream Monoliths Contract

By September, the Corps also hopes to award one of the last major contracts in the project, for the downstream lock monoliths.

“That will basically finish most of the lock,” Getty said, adding that includes placing all remaining concrete, construction of two bridges and building two buildings to operate the lock. Contracts for electrical and mechanical work and an approach walls contract will come later, likely in 2022 or 2023.

“A lot of that work will be concurrent, so these two contracts will be finishing up close to the same time,” Getty said.

The downstream lock monolith contract is expected to take about 4-1/2 years to complete. It will be between $250 million and $500 million in value, Getty said. He expects advertisements for the contract to be posted before spring.

The contract period is 56 months and includes limited rock excavation, placement of about 400,000 cubic yards of concrete in the construction of 51 lock monoliths, fabrication and installation of downstream miter gates, construction of two bridges across the navigation locks, grouting the lock wall foundation, backfill of 1 million cubic yards of soil and fabrication and installation of 17 mooring bitts.

Decreased Navigation Delays

While the Corps has employed helper boats during much of the downstream cofferdam construction, it plans to discontinue their use around mid-January when it is not expected to have any more construction activities vulnerable to impacts. Currently, one helper boat remains, down from two last summer. The reduction was made possible with the installation of a guard cell that protects the cofferdam from boats and vice versa.

“It’s worked well to date,” Getty said.

Getty offered a special thanks to those in the industry who have worked closely with the Corps and the Coast Guard to develop a thorough marine safety plan in use throughout construction, with no significant safety issues reported.

“I think that’s a testimony to the level of cooperation from everybody in making this work,” he said. “They’ve been a huge asset to us throughout the design and construction.”

With the completion of the cofferdam contract in February, Getty said that will end the impacts to the navigation industry using the existing lock until the Corps begins building the upper approach walls, a contract that he anticipates could be 2-1/2 to 3 years away. Two new bridges will be built across the locks in about the same time period.

However, he adds, “We may have some other closures that we’re not aware of now.”

Decreasing time for vessels to traverse Kentucky Lock has always been the driving force behind the economics of the project. Right now, Getty said, waits of 10 to 12 hours are common for vessels before they start their lockages. Most tows required double lockages, taking about four hours for a total of 14 to 16 hours to lock through, typically near the longest wait of anywhere on the country’s inland waterways system. When the new lock chamber comes online, Getty said, it should take most tows about an hour to pass through.

Funding

Keeping up with the Kentucky Lock Addition Project’s projected timeline requires a continual commitment in federal funding. The Water Resources Development Act passed in December includes a Section 902 cost-limit increase for Kentucky Lock, which allows efficient funding for the project. The Corps’ FY21 Work Plan, typically released 60 days after enactment of the appropriations bill, will provide further details, and it usually takes another 30 days after that to receive funds, Getty said.

“Kentucky Lock has been blessed with receiving all the funds we’ve needed and asked for for the last five fiscal years,” he said, meaning that there are not expected to be any delays between contracts.

For Fiscal Year 2021, the Corps asked for $110.1 million, all to go toward the effort of awarding the downstream lock monolith contract. The award would allow a larger base contract with options and is expected to continue funding until the next round of appropriations.

“Kentucky Lock is in great financial shape, and the future looks bright as far as getting enough funds to finish it up efficiently from a financial standpoint,” Getty said.

Caption for top photo: A Johnson Brothers work crew builds a cofferdam cell at the Kentucky Lock Addition Project.(Photo by Lee Roberts/Nashville Engineer District)