The Inner Harbor Navigation Canal (IHNC) Lock is nearing completion of a closure that started in early September to locate and address points of water intrusion that were causing scouring, sinkholes and voids around and under the lock chamber.

The near-60-day closure is the second in four years for IHNC. As in the 2016 closure, the New Orleans Engineer District, the U.S. Coast Guard and the maritime industry have collaborated to reconstitute an alternate route through the Chandeleur Sound to bypass the dewatered lock.

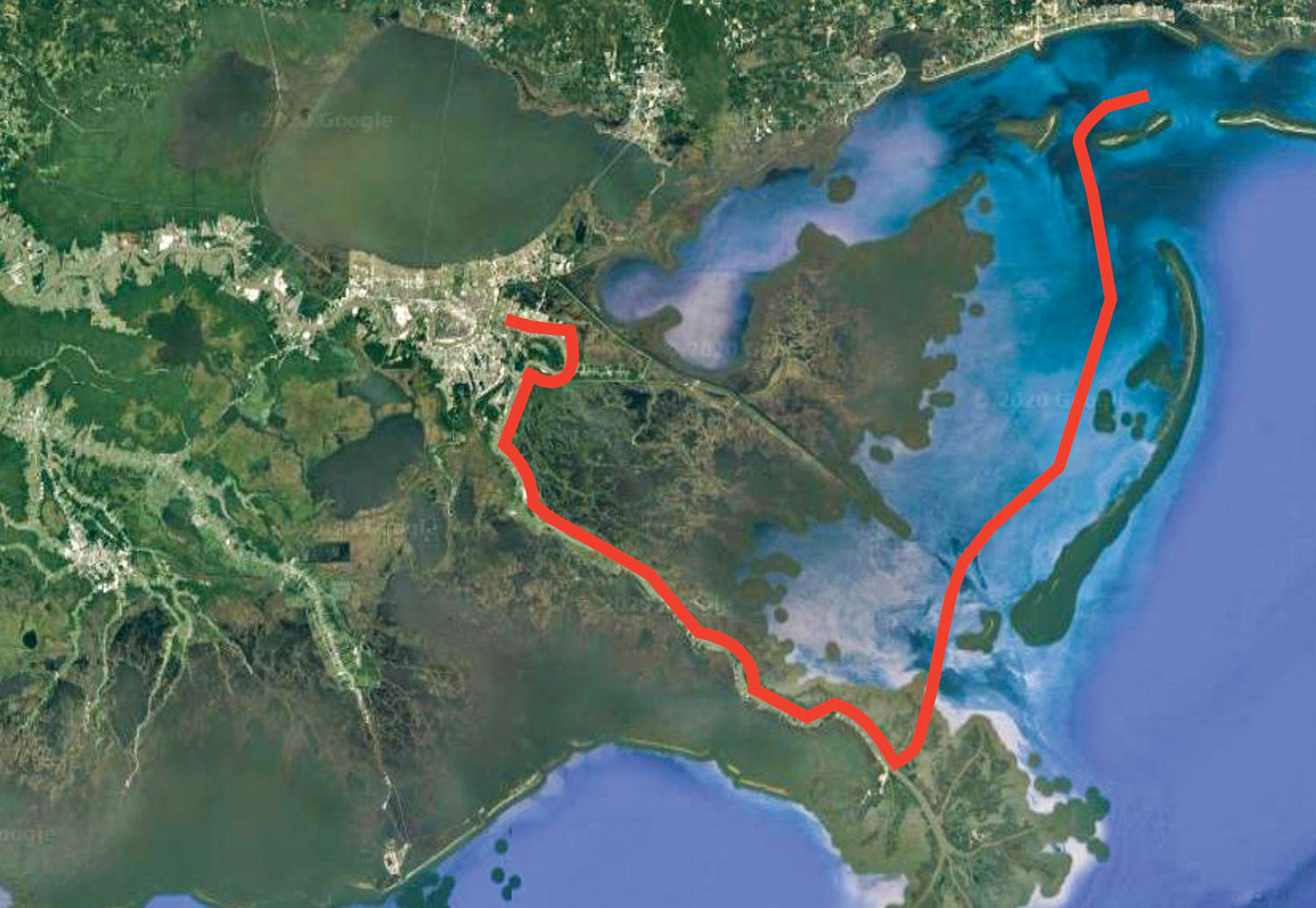

The lock at IHNC is the only navigation structure on the east bank of the Mississippi River for the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW), meaning all east-west traffic crossing the river on the GIWW must use IHNC. To allow for movement on the GIWW to continue through the New Orleans area, the Corps and Coast Guard re-established the alternate route, which uses the Mississippi River below New Orleans, Baptiste Collette Bayou and the Chandeleur Sound to connect to Gulfport, Miss., and the rest of the eastern GIWW.

And as if the work at the lock and the alternate route weren’t challenging enough logistically, the project has been interrupted by five hurricanes making landfall in the region, including Laura and Delta, which made landfall in southwest Louisiana and, more recently, Zeta, which tracked directly over the New Orleans area.

Vic Landry, Gulf Intracoastal Waterway and Bonnet Carré Spillway operations manager for the New Orleans District, said the storms have led to about a three-week delay at IHNC.

“Essentially, every time a storm threatened, we’d have to demobilize and remobilize,” Landry said. “Every time that happens, you’re looking at possibly a four- to five-day impact.”

Landry said the original completion date for the closure was November 5, but the Corps is now eyeing November 25 for reopening.

“Considering all those obstacles, things have proceeded along pretty successfully,” he said.

Landry explained that what’s going on at IHNC, with water being forced through joints in the concrete, is primarily a result of the lock’s age. Next year will mark 100 years since the lock was completed. It fully opened to navigation in 1923.

“You’re looking at a century-old piece of infrastructure that we do a lot of work on to maintain and keep operating,” Landry said. “It’s a smaller lock, so we have challenges there. It certainly needs to be replaced one day soon, but we’re doing everything we can to make sure it’s reliable for the navigation customers and stable.”

With sinkholes accumulating around the chamber over the past year or two, the Corps announced the need and received funding for a closure earlier this year. Possible sources of the water intrusion included brackish water from Lake Pontchartrain on the canal side, the Mississippi River or even a 20-inch water line that goes through the chamber itself. Landry said most problematic of those three would’ve been intrusion from the river.

“That was one of our big concerns,” he said. “If the river was piping and flowing beneath or around the lock chamber, we were concerned with the structural stability of the lock chamber itself.”

Thankfully, a water analysis indicated the primary source of water intrusion was from the lake side.

Once the lock was dewatered, Landry said crews could see water moving like “small geysers” through construction joints in the floor of the lock and in some of the vertical walls in the valve tunnels.

“When the lock was constructed back then, you’d have what you’d call a ‘cold joint,’” Landry said. “It’s essentially sections of concrete poured up against other sections. You didn’t have water stops and the technology we have today. We realized at these joints we had major infiltration.”

Landry said a contractor was able to inject an epoxy fill into those joints to seal off the flow of water through the concrete slabs. As the team addresses the larger points of infiltration, Landry said, it’s revealing smaller infiltration points, which the Corps is proactively addressing.

“With all this work we’re doing to repair the concrete, we think we’re going to be in good shape for the next five to 10 years,” Landry said. “But being a 100-year-old lock, we know we’ll see additional issues down the line. It’s just the challenge of having a 100-year-old piece of infrastructure that continues to degrade due to age. It’s perfectly normal. I think possibly we’ll be chasing these issues in a decade again.”

A second component of the Corps’ work at IHNC during the closure has been locating, measuring and addressing voids beneath the chamber. Landry noted the concrete floor of the lock chamber is a whopping 12 to 14 feet thick.

“It is a massive monolith of concrete,” he said.

A contractor drilled bore holes across the floor to identify the size of the voids, which Landry said averaged only about a foot thick.

“Where we’re locating the voids, we’re pumping some grout—some flowable concrete material—into the voids,” Landry said. “We’ll then come back and fill the cores with new concrete.”

Concurrent with the work to stop water infiltration and fill voids around the chamber, the Corps has been addressing ongoing issues with the lock’s fill valves. There’s a contract in place to remove all the old valves and replace them with all-new, modern equipment.

“We’ll have four brand new main operating lock valves, so that gives us a lot more redundancy for the future as well,” he said. “This is something we’ve been wanting to do, and we could’ve done it in a wet condition with divers. But having the lock dewatered gave us the opportunity to get in there and do it more accurately and do it right.”

The Corps is also overseeing installation of a phased new guidewall at the river side of the lock and new mooring dolphins on the canal side. The Corps’ hired labor unit is also making repairs to the existing timber guidewall. Simultaneous to the lock work, the Port of New Orleans, which originally built the lock and the adjacent drawbridge over the lock on St. Claude Avenue, is doing rehabilitation work on the bridge.

Landry said all the work in and around the lock bodes well for IHNC in the near term, but it’s no answer to the long-term issue of the lock itself.

“We can continue to do this, but the economic impacts to the nation are tremendous when we have to shut this lock down two to three months at a time,” Landry said. “That’s really not something we want to be doing every five to eight years because of the strain it puts on the commerce of the nation.”

And it’s not just the age and fragility of the lock. Its small dimensions—640 feet by 75 feet—create an incredible bottleneck on the GIWW, which is one of the nation’s busiest and more important waterways.

Jim Stark, president of the Gulf Intracoastal Canal Association (GICA), said the closure illustrates the urgent need to replace the lock.

“Our industry continues to be very concerned with the reliability and resiliency of the IHNC Lock,” Stark said. “This was a topic discussed at last week’s Inland Waterways Users Board. Industry representatives strongly urged the board and the Corps to expedite work to complete the Corps’ General Reevaluation Report and Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement for the replacement lock project. An earlier version of the report and analysis indicated a very positive benefit-cost ratio, and we believe the replacement project would have competed well for a priority slot on the Users Board’s Capital Development Plan.

“However, now the Corps is going back to work to improve certain portions of the plan. This will take time to complete and will certainly put more strain on the viability of the lock,” he continued. “I think all agree a new lock is needed, and sooner rather than later, and hope the Corps can move forward quickly. GICA and its industry members are committed to assisting in this effort any way we can.”

Even so, Stark echoed Landry in praising the partnerships between the Corps, Coast Guard, industry and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that have made reconstituting the alternate route a temporary solution while the lock has been closed.

“During the busy storm season, our government partners have been extremely responsive after each storm event in getting necessary surveys of the route and restoring aids to navigation,” Stark said. “Those efforts have minimized route closures and restored commerce as soon as practicable. Due to tropical storm impacts and typical late summer weather events on the route, the usage rate has been a bit lower than in 2016. However, roughly 200 successful transits have been completed, enabling tow operators and customers to avoid significant delay costs had they been forced to use the river system or alternate transportation modes to move cargoes to the east and vice versa.”

Landry also praised his team along the GIWW, many of whom suffered personal loss during this year’s hurricanes, yet remained dedicated to the work of maintaining commercial navigation on the canal.

“I can’t say enough about our team and our staff out in the field,” Landry said. “They’re very resilient, very dedicated to the mission, and they have a great get-it-done attitude for every storm. Most all our employees, especially out in the Lake Charles area, many had devastating impacts and several lost their houses totally, but these guys are coming to work and locking boats. They understand the critical nature of the mission and our navigation customers.”

Even with landfalling hurricanes impacting the GIWW repeatedly this year, the Corps, Coast Guard and industry representatives have been able to work together and employ lessons learned from past events, like recent guidewall work at Calcasieu Lock, to quickly reduce queues as waterways reopened after storms.

“Industry and its government partners have worked together for years to ensure commerce moves as smoothly as possible on the GIWW,” Stark said. “The relationships that GICA and its membership maintain with our government partners are almost second nature, and they become an invaluable asset during a hurricane response.”

Caption for photo: Map shows the alternate route that towing vessels must use to get from the Mississippi River to the eastern GIWW during the closure of the Inner Harbor Navigation Canal Lock.