Near a bend in the Mississippi River above the Sunshine Bridge in Louisiana, scores of vehicles—some cars but mostly trucks—are parked along the crown of the levee and all along the batture. It’s January 14, and a weekend of rain has left the river batture a muddy, rutted mess. The river here is on the rise.

Moored on the east bank of the river is a sprawling quarter barge that bears the emblem of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. There’s also a towboat and barge tied up, and crew boats are ferrying scores of workers to and from the quarter barge and a worksite farther upriver.

It’s lunchtime for the crew of the Corps of Engineers’ Mat Sinking Unit, and crews are ferrying between the quarter barge and the unit just upriver.

“Mat sinking” on the Lower Mississippi River dates to the 19th century, when Corps crews would weave together a “mat” of willow trees, float them out into the river, then sink them with stones. The seasonal task, which usually spans the low-water months, was conceived to prevent erosion, protect key areas of the riverbank and ensure safe and reliable navigation.

After the Great Flood of 1927, with the launch of the Mississippi River and Tributaries Project, the Corps undertook the task of designing and building a new, robust revetment operation. The current Mat Sinking Unit came online in 1948, with some significant operational improvements added in the 1960s.

The septuagenarian MSU is indispensable for the communities and industries that line the Mississippi River. As the mighty Mississippi tumbles toward the Gulf of Mexico, especially during high water, the powerful and speedy current scours as it goes. Left unchecked, that scouring would eventually undermine, in spots, the stability of earthen levees and fixed structures along the river and threaten the ship channel that’s the economic lifeblood of much of the country.

“For more than 70 years, the Mat Sinking Unit has taken on the unique and important task of preventing erosion and maintaining navigation up and down the Mississippi River,” Vicksburg District Engineer Col. Robert Hilliard said following the close of the MSU’s 2019 revetment season. “The Mississippi River serves as a vital commercial waterway and drainage system for the nation, and the hard work of the unit allows it to perform those crucial functions.”

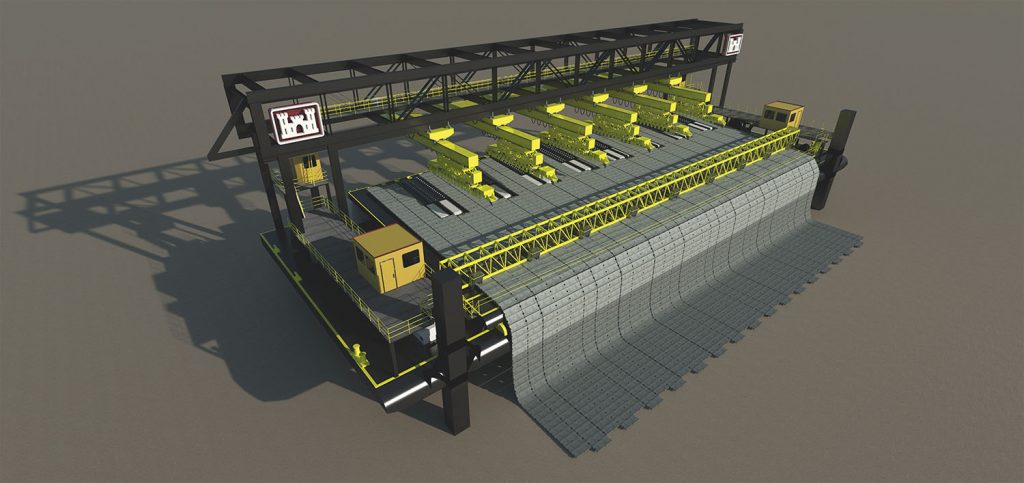

Despite its age, the current MSU is an engineering wonder. Instead of woven willows, mats today consist of cement “squares.” A square measures four feet by 25 feet. A set of four gantry cranes each move squares two at a time from a deck barge onto the mat laying barge, where they’re stitched together into a massive cement blanket. Crews working on the mat laying barge use specially-designed pneumatic tools resembling jackhammers to bind the squares together with copper rods. When a row of squares is complete, a complex web of wires and winches allows the finished mat portion to slide overboard.

But that’s only a fraction of the system at work. The mat itself is anchored to the riverbank and to bulldozers on the batture. The mat laying barge sits parallel to the bank and is moored to a floating plant, which sits perpendicular to the bank (and the current). The mat laying barge slides laterally along the plant and moves away from the bank as the mat is laid. To stand against the massive force of the river’s current, wires run from the floating plant to an anchor barge, which is secured to the bank just upriver.

It takes a sizable and uniquely-trained crew to accomplish the revetment task. The crew consists of about 50 full-time Corps team members and 220 seasonal employees who live on the quarter barge and work 10-hour shifts a dozen days at a time.

As complex as the system is, the MSU lays an enormous amount of squares each year. Barges serving the unit carry about 500 squares, and crews can lay about six or seven barges worth of squares in a day, rain or shine.

“The only things that keep us from working are ice and lightning,” said Barry Sullivan, Mat Sinking Unit chief.

In an average season, the team, working from below Memphis, Tenn., to south of New Orleans, lays about 120,000 squares in the river, said Ed Adcock, chief of the revetment section for the Vicksburg Engineer District. Adcock said during the 2019, though, that number jumped to about 170,000 squares in response to last year’s historic flood season on the Mississippi River. Typically, the unit starts on one side of the river and works down. Because of last year’s high water, though, Adcock said the team had identified 25 sites in need of attention in the 2019 revetment season. Fearing an abbreviated mat laying season, the team opted to move up and down the river, attacking the greatest needs first.

It’s a critical and cooperative effort of the Memphis, Vicksburg and New Orleans Engineer districts unmatched on any other river system.

“It’s unique to this,” said John Cross, an engineer with the Corps. “It’s the only thing like it in the world.”

ARMOR 1

Cross is project manager of ARMOR 1, the next-generation Mat Sinking Unit under construction now at Thoma-Sea Marine Constructors’ Lockport, La., shipyard. Cross said, as good as the 1948 Mat Sinking Unit has been, ARMOR 1 is going to be a huge leap ahead.

Whereas the current MSU employs four manually-operated gantry cranes, the new ARMOR 1 will feature six robotic cranes. Carnegie Mellon University’s National Robotics Engineering Center is designing the robotics system aimed at automating and modernizing the mat laying process, while Bristol Harbor Group Inc. is designing the barge itself.

Cross said, in designing the new unit, the design team prioritized safety, efficiency and reliability.

“Safety was No. 1,” he said. “We wanted to get it in compliance with the American Bureau of Shipping’s standards. We wanted to meet all current Corps of Engineers safety standards. So the new unit will be that, which is really a blessing.”

Cross said, from an efficiency standpoint, they set out to drastically exceed the current MSU’s capabilities.

“We didn’t want to recreate the old one but in a 2020 version,” he said. “We wanted to make sure we take advantage of this opportunity to increase our productivity.”

Cross said, while a really good day on the current MSU is 2,000 squares laid, the unit actually averages around 1,300.

“Sometimes our process out there is very slow,” Cross explained. “It’s very manual. It was 1948. No automation, no sensor, nothing. A lot of stuff is done by hand and arm signal.”

With the new unit, Cross said the team will be able to lay 4,000 squares a day. And that’s at the bottom end of the spectrum.

“All the robotics, the systems, the winches and cables, everything is designed for a 4,000 bottom threshold,” he said, “with the potential to do more.”

From a reliability standpoint, Cross said machinery on the current MSU breaks all the time. And when it does, replacement parts often have to be fabricated on site. There’s an entire shop on board the floating plant dedicated to repairing the pneumatic stitching tools. The unit is even equipped with a World War II-era lathe for turning new parts.

“The manufacturers don’t exist for some of that machinery,” he said. “They went out of business years and years and years ago.”

In contrast, ARMOR 1 will be replete with sensors and automation that will prevent those types of machinery breakdowns.

Cross said the crew will be much smaller aboard the forthcoming ARMOR 1, but it will be far from “person-less.”

“We’ll still have people, so it’s not like this weird dystopian thing where there’s nobody on it,” he said. “We will have less people, but we’ll have less people doing the dirty, dangerous jobs.”

Instead of dozens at work on the deck at one time tying the squares together, around 10 crew members will work on deck focusing more on quality control. There will still be deckhands, shoreside dozer operators and support staff—those jobs won’t change. Cross said the Corps is partnering with Hinds Community College in Vicksburg to develop a training program for the new, state-of-the-art unit. Workers trained in those technology-centered roles will likely be hired full-time rather than seasonally.

Cross said he expects full sea trials of ARMOR 1 on the Mississippi River to commence in December 2022, with its first full season on the job in 2023. Cross said ARMOR 1 has some big shoes to fill.

“This last one’s been laying mats since 1948,” Cross said. “So we’re planning a 50-year lifespan at least for ARMOR 1.”

The Corps stood down the Mat Sinking Unit on January 21 due to high river levels, officially ending its 2019 season. Once low water returns later this year, the MSU crew will continue its mostly unseen yet enormously important task of laying mats on the riverbed of the Lower Mississippi, protecting communities and preserving a unique practice that dates to the time of steam engines and sternwheelers.

Caption for top photo: MSU crew members transfer concrete squares from a deck barge onto the mat laying barge. Each deck barge holds about 500 squares, and the MSU crew can lay six or seven barges’ worth of squares per day. (Photo by Frank McCormack)