Mariners on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers running from Cincinnati to New Orleans might be surprised to learn that, a little more than 100 years ago, there was a man who made the trip on foot. Not on the bank, mind you. No, he walked on water.

Charles Oldrieve was a showman and inventor who became famous for designing and using a pair of floating shoes. This was especially astonishing back in a time before water sports were common.

Oldrieve was born in 1868 and grew up in New England. When he was still a young lad, he ran away with a circus, staying with the show for six years. He tended animals, and eventually did stunts.

While in a small town in New York state, the circus went belly up. Oldrieve was left penniless. Desperate for work, he came up with the idea of walking on water by using floating shoes. Rigging up a crude pair of canvas shoes, he gave a walking-on-water exhibition on a small river nearby. It was a fiasco. He nearly drowned.

By about 1895, he had perfected a pair of shoes that was much more successful. Still in New York state, he attracted a lot of interest along the Hudson River and on Long Island Sound. Thousands of people witnessed his exhibitions, and the press covered it all. Oldrieve took his show to different cities around the country, including New Orleans.

The showman and inventor even went to Cuba in 1897, shortly before the Spanish-American War broke out. In addition to walking on water there, he started staging miniature naval battles. He built miniature naval vessels, and proceeded to blow them up. While giving one of these exhibitions on Havana harbor, he was attacked by a huge shark, which bit off a piece of his foot, nearly killing him.

As soon as the wound had healed, he continued his work, He would have stayed in Cuba much longer, but he was deported by the Spanish government. They were worried that his dramatic and fiery exhibitions of naval battles were inciting the Cubans to insurrection.

On a trip to Canada, Oldrieve met Caroline Trott, the daughter of a Nova Scotia fisherman. She was a woman of athletic ability and strong physique, accustomed to rowing and other outdoor activities. She became Oldrieve’s wife and water-going companion.

Caroline is a very important part of our story. She billed herself as a “world champion oarswoman.” Her husband billed himself variously as Captain Oldrieve and Professor Oldrieve. These claims and titles are all part of showmanship, but the Oldrieves would live up to their boasts.

A Wager

In late 1906, two men with money to play with wagered on whether Oldrieve could use his floating shoes to walk on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers all the way from Cincinnati to New Orleans, a distance (back then) of 1,513 miles. E.J. Weatherton of Louisville bet that it could be done in 40 days. Betting against him was Alfred Woods, a “sporting man” from Boston. The wager was for $1,500, the equivalent of about $125,000 today. Oldrieve’s stunts had now become much more interesting.

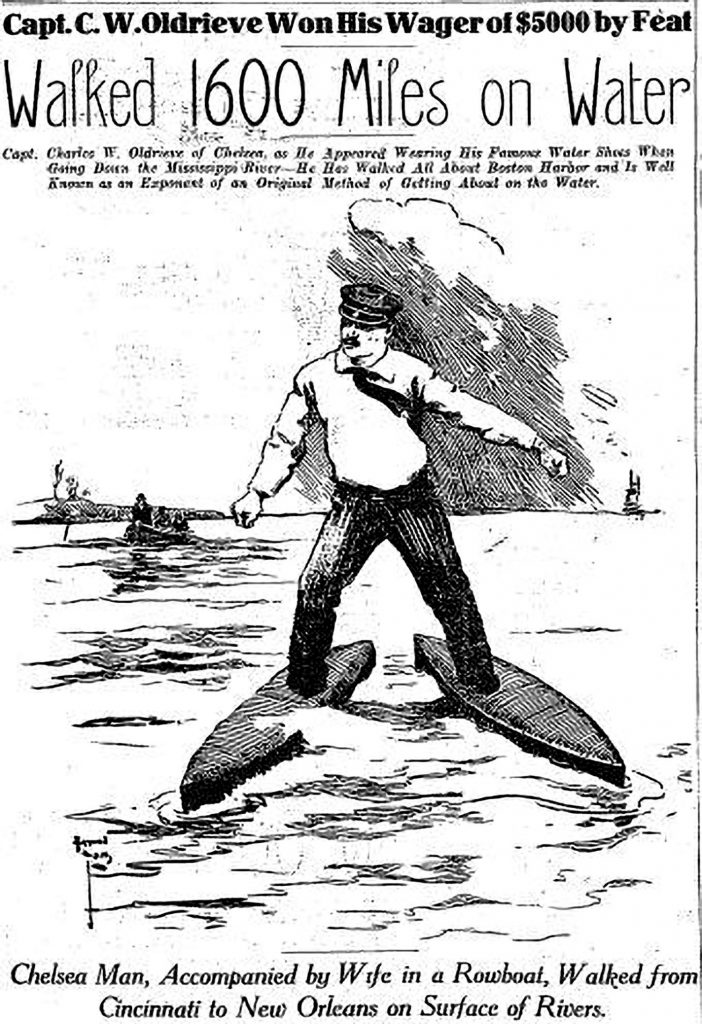

The floating shoes themselves were interesting, and people had trouble deciding what to call them. Various reporters described them as seven-league boots, foot boats, skiff-like shoes, canoe-shaped shoes, and moccasins.

Whatever they were called, the shoes were made of red cedar, 3-1/2 feet long by 6 inches wide, with the depth also 6 inches. Some reports said they were 4-1/2 feet long. At the bottom, sides, and heel they were perfectly square, but they were slightly pointed at the toe like a canoe or wooden shoe. Near center were the receptacles for the feet. Before putting on the wooden shoes, Oldrieve would encase his feet in heavy rubber boots reaching to the thighs, thus protecting his legs from the water. After placing his feet in the tight-fitting wooden shoes, he would lash a rubber “bandage” over the whole affair, making it all practically watertight. By the agreement of the wager he would be permitted to go to the boat and empty the water from the shoes whenever necessary.

As he walked on the water, the shoes would sink three or four inches below the surface. He propelled himself with a stroking motion, sort of like skating, although it apparently required more exertion than skating. Walking along, he resembled a man floundering along in mud, unable to entirely lift his feet.

A key component of the floating shoes was hidden on the bottom. The “soles” or bottoms had a number of hard rubber scoops or flaps, attached so that they would lie flat against the bottom when he shoved his foot forward, and open to resist the water pressure as he pushed backward. Altogether the shoes weighed about 20 pounds each out of the water, but of course their buoyancy in the water neutralized their weight.

Oldrieve started his river walk on New Year’s Day, 1907, departing Cincinnati with a tiny flotilla consisting of a motor launch with three or four men on board, then Oldrieve himself “on foot,” then Mrs. Oldrieve in her 14-foot rowboat. Caroline, the able rower, was there to rescue her husband if needed.

The motor launch was actually a small, gasoline-powered sternwheel houseboat. Its purpose was to carry observers from both sides of the bet, and to serve as a place for Oldrieve to sleep every night. The crew were two river mariners from Cincinnati: pilot A. L. Madden and engineer Arthur James. Oldrieve’s backer, Weatherton, would be on board for most of the trip. According to the terms of the wager, Edward Williams of Boston, representing naysayer Woods, could also show up any time, ride along, and keep an eye on things.

Oldrieve and his party almost met a dismal end just few days into the trip. On January 6, the flotilla went over the Falls of the Ohio, near today’s McAlpine Lock and Dam. Instead of navigating safely through the Portland Canal, Oldrieve and his wife and the boat crew were sucked through the rapid currents of the falls. The river was at a very high stage, when steamboats would typically navigate the falls, but smaller craft (and water walkers) could be knocked around like corks. Oldrieve deftly stayed on his feet, and Mrs. Oldrieve had no trouble controlling her rowboat, but the motor launch was damaged so badly that it caused a 24-hour delay. Oldrieve admitted that bumping over the rocks was a “thrilling experience;” Caroline said she enjoyed the excitement, although the whole time she was concerned about the men in the motor launch.

As the trip continued and Oldrieve racked up more miles, he figured out that the best weather for his water-walking was just a light wind at his back. A strong headwind would of course hinder his progress, but a strong tailwind would catch the backs of his shoes and make them turn inward. In still water with no wind, he could walk at a pace of about 2 mph. The best stretches were when he was going with a current of about 7 mph., with a breeze at his back. He could make about 10 mph. in those conditions.

As the water-walking party progressed downriver, they were met by bigger and bigger crowds. Steamboat whistles would announce their arrival, businesses would shut their doors, schools would let out, and crowds would line the river banks. Even away from the towns, hardly an hour ever went by when there weren’t one or more skiffs rowing alongside.

By January 14, Oldrieve was approaching Paducah. He spent the night upstream at Smithland. The next morning, when he emerged from the mist abeam Owen’s Island, steamboat whistles blew to alert the populace. Barber shops, grocers, and other businesses quickly closed. Soon thousands of Paducahans lined the riverfront and crowded aboard the steamers tied up to the wharfboat at the foot of Broadway. Half-shaved men still wearing their barber’s bibs stood next to children playing hooky from school.

Two skiffs put out from shore, but Oldrieve insisted he had to keep walking in order to reach the Mississippi River by nightfall. He was cheered from shore anyway, and he fired off “dynamite crackers” in response.

On January 16, crowds in Cairo began to form as early as 9 a.m. Oldrieve was delayed by an accident on the launch. They laid over at Mound City for more than two hours at midday, then continued to Cairo. By the time Oldrieve arrived at 4:15 p.m., 10,000 people thronged the Cairo riverfront. Oldrieve seemed to be in fairly good condition in spite of the days of physical exertion. He told locals that he’d heard of a dangerous passage through the chalk banks of Hickman, Ky., and wanted to pass that point during daylight. He was 13 hours behind schedule by this time. He told a New Orleans Daily Picayune correspondent that if he lost as much as three days time he would give up the walk. The strain was significant, and he had had a high fever the night before.

On January 22, Oldrieve arrived at Memphis much earlier than expected. The party tied up for the night near the bridge. Charles was now in very bad health, and Caroline had given up the skiff gig, being confined to the launch with chills. Eighteen of their 40 days remained. Oldrieve had made nearly 60 miles the day before, and needed to average 44 miles a day to win.

The flotilla passed by Lake Providence at 8 a.m. Quite a few people there were disappointed that the river walker had passed by so early in the morning.

At 3 p.m. on February 2, Oldrieve passed Natchez without stopping. He “cut over the breakwater” and hugged the Louisiana shore. Back then there was no Giles Bend Cut-Off along the ridge at Mile 367 AHP. Instead there was a sharp point on the west bank right above Vidalia.

Below Natchez, Oldrieve encountered some difficulty with heavy drift because of the unusually high water. The river was running so hard that some of the steamboat lines out of Memphis had tied up.

Within days, with Louisiana on both sides of the river, the timing was looking good for a successful finish. On February 9, they stopped for lunch at Edgard, La. They left at 2:30 p.m., and arrived at Ama at 6:30 p.m. They were a little more than 20 miles above the finish line at Canal Street, and the plan was to get back underway at 6 o’clock in the morning. They had to get to New Orleans by a quarter past noon.

Oldrieve actually got underway from Ama at 10 minutes before 6 a.m. He was not in the best of health, and had told people at Edgard that he was suffering from rheumatism and dizziness. But on he went, with Caroline rowing alongside and shouting words of encouragement.

The last miles of flat landscape must have looked bleak to Oldrieve. In 1907 there was no Huey Long Bridge yet, no Greater New Orleans Bridge and no skyscrapers.

Soon, though, the docks of the Port of New Orleans came into view. From Jackson Avenue on down, the wharves were crowded with people. Steamboats and skiffs floated nearby.

The finish line was within sight, but trouble almost brought the affair to a terrible end. As he came abeam Julia Street, Oldrieve got caught in a swirl of current. Caroline saw the danger and called out, “Avoid the eddy, Charlie!” She tried to row toward him, but the outer part of the eddy pushed her away.

Charles was about to be sucked under a barge at the coal fleet there. Several deckhands nearby saw what was about to happen, and ran to the edge of the barge, lay down and reached for the embattled walker. They held on to him to let him regain his balance and his footing, and to let him catch his breath. Once the swirling current looked favorable, Oldrieve pushed off again, and walked across the Canal Street finish line with minutes to spare.

There were celebrations, of course, but both Charles and Caroline spent several days recuperating. They ended up staying in New Orleans for quite a while, putting on the usual waterfront exhibitions, both on the river at Algiers Point and on Lake Pontchartain. At West End, Oldrieve became a regular attraction, just like in circus days.

Unhappy Ending

Unfortunately, the Oldrieve story has the saddest of endings. Just a few months after the spectacular success of the Cincinnati-to-New Orleans wager, Caroline was severely injured in a 4th of July fireworks accident at Greenville, Miss. A few days later, at the age of 31, she died of her injuries.

Charles was inconsolable. Five days later, he committed suicide. In the words of a Daily Picayune headline, Oldrieve refused to outlive his beloved wife.

Had it not been for his death, Oldrieve might have accomplished the feat of walking across the English Channel. Confident that he could achieve what numerous swimmers had done there, he was preparing to make the crossing from either the French or English side in what might have been the most remarkable achievement of his career. There was a $10,000 wager on it, provided that he finished the crossing within 30 days. Mrs. Oldrieve had planned to accompany him.