A mariner on the Lower Mississippi could pass by the New Orleans riverfront a thousand times and not even know it, but there’s a ship buried there, near the middle of the river, just a few hundred feet downstream from the Crescent City Connection.

The ship, the Union Faith, collided with a loaded oil barge 50 years ago, on Easter Sunday 1969. The barge broke in two, and the ship immediately burst into flames. It burned for several hours, finally sinking near what we now call the Riverwalk.

The loss of life was extensive, including half the ship’s crew, plus one local pilot. The Corps of Engineers ended up having a 600-foot trench dug to serve as a grave for the ship, and that’s where it lies to this day.

The Union Faith was a Taiwanese freighter, and an interesting sight to see. Even by 1960s standards it looked old-school. A retired captain from the 1950s described it and its sister ship Union Freedom as looking like “mini Queen Elizabeths,” like passenger liners from an even earlier era. There was a good reason for that. The two ships were built for the Silver Line in London in 1948 as exclusive passenger ships, each designed to carry no more than 12 wealthy passengers in high style. Each ship was 503 feet, 6 inches in length, with a 65-foot beam.

Just six years after they were built, both ships were sold to the Cunard Line and were used for general cargo in the Atlantic trade. Some of the luxurious passenger amenities remained, and ship’s officers slept in first-class cabins. Their wardrooms were originally passenger lounges, built as half-timbered pubs with fireplaces and oak beams. The Union Faith’s wardroom was decorated with antique guns, muskets, and pewter mugs and plates. The sister ship had antique swords and daggers hanging on the bulkheads. There were even grand staircases amidships.

But the most obvious passenger-liner characteristic could be seen from miles away. Each ship had two tall funnels, raked back at a jaunty angle. Actually, the forward stack was a dummy, just for looks. The captain’s cabin was inside at the base of the forward funnel at lifeboat deck level. The next deck up housed the radio shack and the chartroom. Above that was the radar shack, and finally above that was the bridge lookout deck.

In 1963 both ships were sold to Taiwanese owners and soon became regular visitors to New Orleans. Just in the 12 months preceding the Union Faith’s last voyage, the ship called at New Orleans at least twice, in April and August of 1968. The ship was set up to carry a wide variety of cargoes. There were five cargo hatches. Hatch No. 3, shoehorned in between the two funnels, was outfitted with four deep tanks for carrying vegetable oils.

The Union Faith came up the Mississippi River on Saturday, April 5, 1969, and dropped anchor in General Anchorage below Algiers Point. The ship had come from the East Coast with a mixed cargo including cotton cloth, salt, toys, handbags, household goods, and footwear.

The following evening, Easter Sunday, a local pilot boarded to bring the ship to its destination upriver. The pilot was Crescent 49, Capt. Kenneth H. Scarbrough. It was to be a short trip, just up to what in those days was referred to as the Cotton Warehouse, on the east bank near mile 99.5 AHP, or a little more than a mile above the Harvey Lock forebay.

As the Union Faith was getting underway, the mv. Warren J. Doucet was coming downriver pushing three loaded crude oil barges, two long and two wide, headed for the Algiers Canal Lock. The boat was uninspected, and the captain, Tillman LeBlanc, was unlicensed. The Warren J. Doucet was an 800 hp. twin-screw hawser tug built in 1967. The boat was 65.4 feet long, and the length of the tow was 570 feet. An assist boat, the Cat & Mitch, was made up at the port stern.

The Carrollton gage was at 8.8 feet and rising. The speed of current was about 3 mph. The wind was out of the north at 7 mph.

As was, and is, the custom, the downbound tow favored the west bank, but began crossing to the east bank at a point above the Greater New Orleans Bridge. (There was only one span at the time, before the second span was built and the name Crescent City Connection was coined.) Before beginning his turn to the east bank, Tillman broadcast his intentions on the 2738 khz. frequency.

Capt. Scarbrough on the Union Faith also broadcast his position and intentions before coming up around Algiers Point, but he was on the 156.65 Mhz. frequency (channel 13), and had communicated with two other vessels on that channel.

While pointing his tow toward the east bank, Tillman saw the lights of the Union Faith coming around Algiers Point. Also by custom, the Union Faith began crossing to the east bank below the bridge. Tillman attempted to call the ship on his frequency. Then, with the two vessels a little more than a mile apart, he blew two whistles. The whistle signal was not acknowledged or returned by the ship. When the vessels were about a half mile apart, Tillman blew four whistles, put his engines in full reverse, and turned his spotlight on to illuminate his tow. Finally, the ship sounded four whistles and reversed its engine.

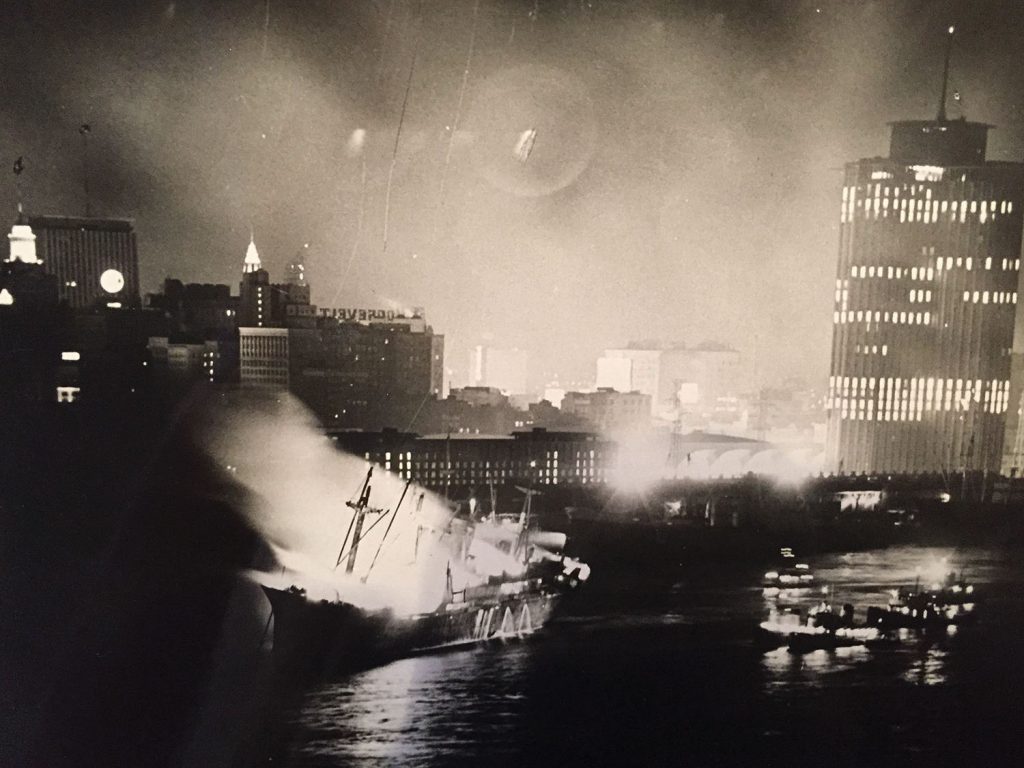

By this time, the Union Faith had just come under the GNO Bridge. At 7:15 p.m., the bow of the Union Faith struck the Doucet’s lead barge, IOC No. 7, at a 45 degree angle about 100 feet from the head of the barge. The barge immediately buckled and wrapped around the bow of the ship. Sparks from the impact ignited the barge’s cargo of crude oil, very quickly enveloping the ship in flames.

The Doucet and its other two barges survived the collision, but the Union Faith began drifting back down toward the bridge, with flames and smoke reaching up as high as the span. The barge soon broke completely in two, the two parts eventually drifting away and sinking, but the floating crude oil kept fueling the fire surrounding the ship.

As the Union Faith drifted under the bridge, heat from the fire damaged the bridge itself and caused vehicular traffic to be stopped and turned around.

Tugs and other small craft rushed to the scene and were able to rescue some of the Union Faith’s crew who had managed to jump overboard. Other crew members couldn’t find any water to jump into that didn’t have burning oil on it.

At this point, the Crescent pilot, Kenneth Scarbrough, performed what other mariners would later call a heroic and selfless act. Abandoning the ship’s bridge, he ran forward, into the flames on the main deck, in order to release the anchors and prevent the burning ship from drifting toward the bank and causing further destruction and injury. The last anyone actually saw Scarbrough alive, he was rushing forward into the flames. Within minutes, the anchors dropped.

Scarbrough, having met the steamer President just minutes earlier, no doubt knew that hundreds of passengers would still be on board the excursion boat, and in harm’s way.

The master and crew of the tug Cappy Bisso, in a remarkable display of courage and rivermanship, caught a line around one of the anchor chains to slow the ship’s downstream momentum, and the anchors finally held. The ship burned for hours, eventually listing and then sinking at about 2 a.m.

Potentially disastrous fires and destruction on shore were averted, but 25 crew members on the Union Faith died, trapped on board the burning ship. Their remains were never recovered.

The sunken ship was a hazard to navigation, a very large channel obstruction. After reviewing the alternatives, the Corps of Engineers decided that the Union Faith would have to be buried right there. The Corps awarded a $1.6 million contract to the Foundation Company of Canada, Ingram Contractors of Harvey, La., and Atlantic Tug & Equipment Company of Buffalo, N.Y. The contract stipulated that there would have to be at least 55 feet of water over the ship at low river.

The contractors dug a large trench and generated artificial “landslides” to induce the ship to drop into it. The project was successful. On the morning of October 31, 1970, the Union Faith slid down into its grave.

The Union Faith disaster is one of several high-profile marine incidents that caused Congress and the Coast Guard to make major changes that mariners today might take for granted, including licensing of towboat personnel, improvements in barge navigation lights, and a requirement that vessels carry radio equipment compatible with other vessels on the same waters.