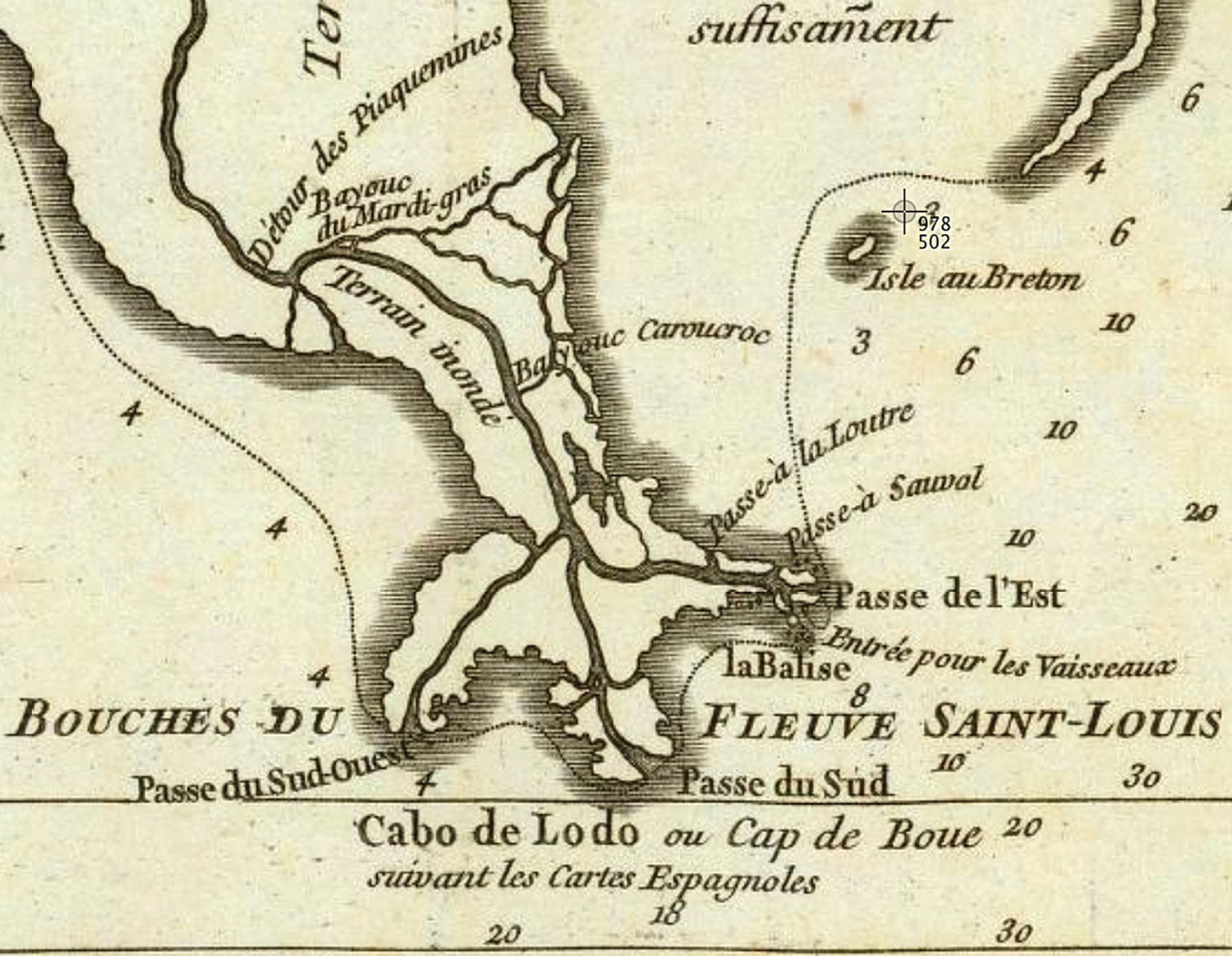

Top photo (click photo to enlarge): Detail of a c. 1752 French map of Louisiana showing Bayouc du Mardi-gras as well as “Piaquemines” Bend. The map also labels the delta in French as the “mouths of the Saint Louis River.” The spelling “Bayouc” is apparently archaic French.

The first Mardi Gras celebration in the United States was at Mobile, Ala., in 1703, but Mardi Gras was literally put on the map four years earlier on the banks of the Lower Mississippi River.

In fact, there have been at least two places on the Lower Mississippi named for Mardi Gras, separated by 25 miles and more than 300 years.

When the French-Canadian explorer Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville found the mouth of the Mississippi River in March 1699, he and his men paddled their longboats through Pass A Loutre, then made their way about 20 miles upriver and made camp on the east bank. The location was near Mile 21 AHP, at what we now call Bolivar Point. The day was Fat Tuesday, March 3, 1699, so Iberville named the place Pointe du Mardi Gras.

The following year, in a Carnival coincidence, members of Iberville’s second expedition passed by the same spot on Mardi Gras Day and gave the name Bayou Mardi Gras to the “small strait or pass” leading from the river out into Breton Sound. That bayou was at Mile 20 AHP, immediately downriver from the future Fort St. Philip.

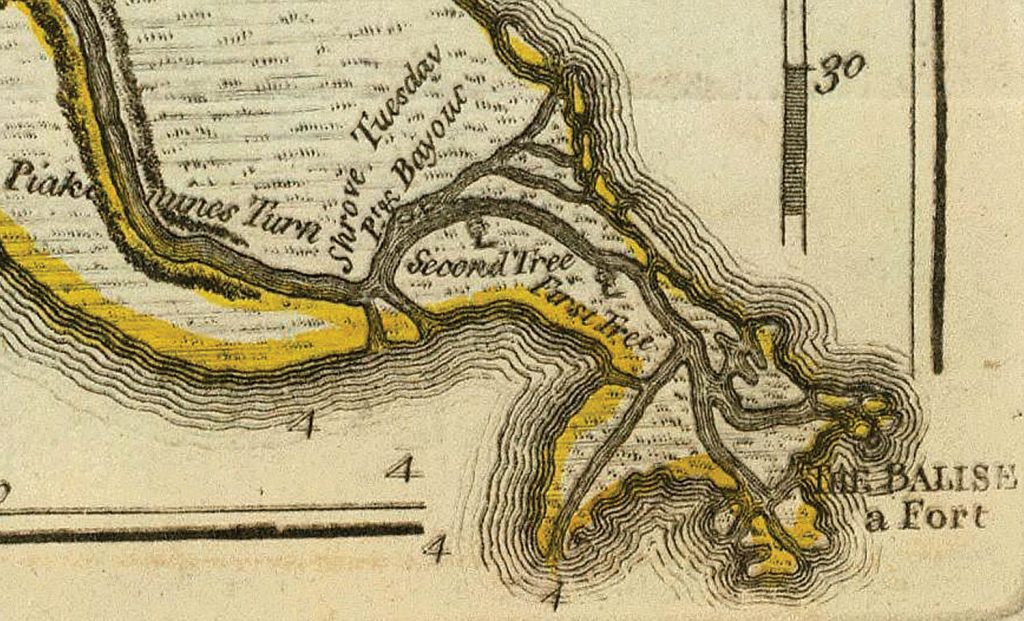

The name stuck for more than 100 years. A map published in 1752 shows “Bayou du Mardi-Gras.” An English mapmaker in 1775 preferred to anglicize the location as “Shrove Tuesday Pt. & Bayou.”

In 1801 Josephine Favrot, the daughter of the Spanish commandant at Fort St. Philip, complained in a letter to a friend about the dismal walk home from the fort. It was “necessary to walk straight, because if you make a false step to the left you will fall into the grasses; if [to the right] into Bayou Mardi Gras.”

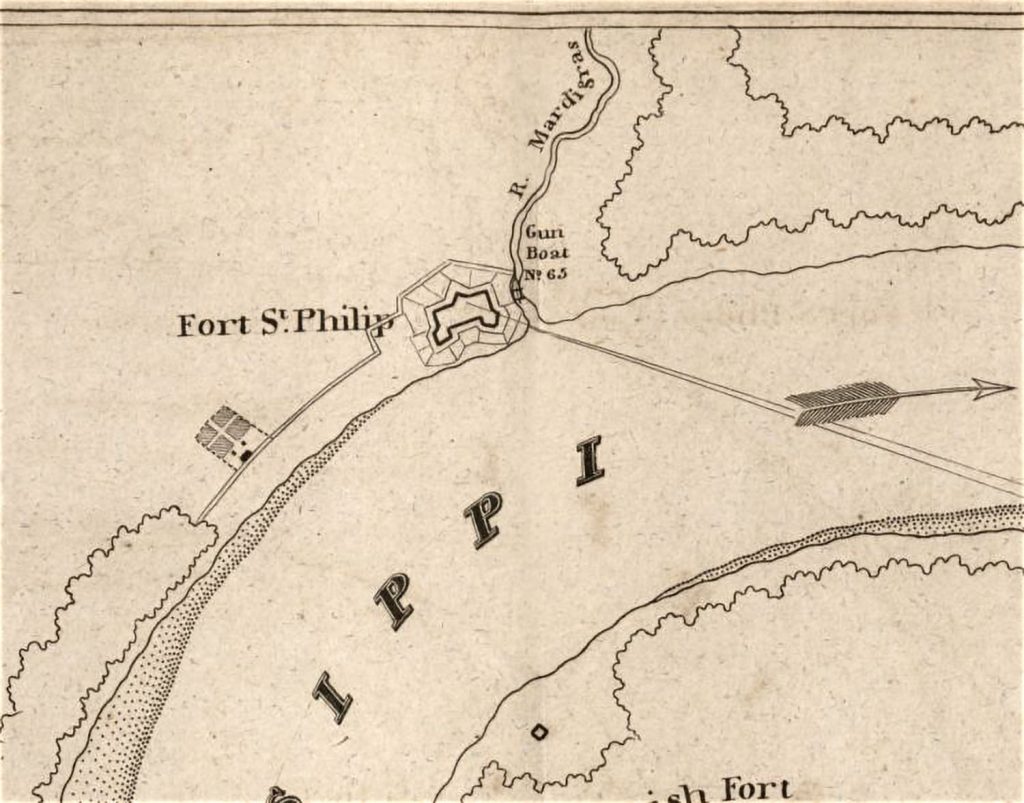

In 1815, after the Battle of New Orleans and the British attack on Fort St. Philip, a military engineer for Gen. Andrew Jackson drew up a map of the area showing the “Mardigras” bayou directly adjacent to the fort, almost like a moat on the downriver side, complete with a gunboat.

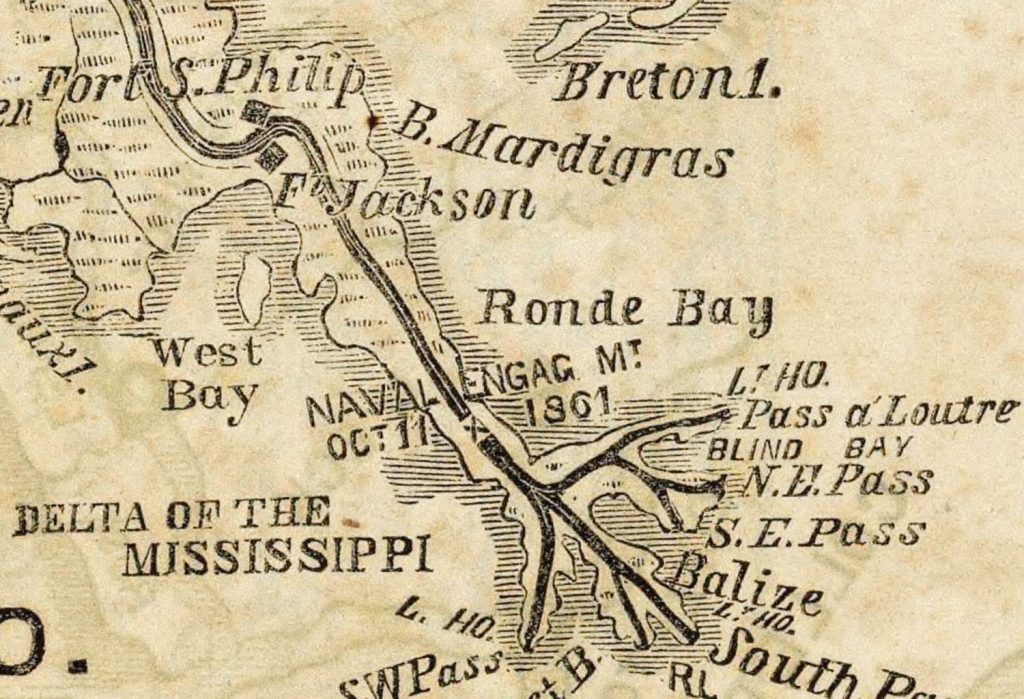

As late as 1861, a map published in the New York Herald indicated “B. Mardigras.” Within a year or two, though, in the middle of the American Civil War, mapmakers were calling it Fort Bayou, and the name on the point was nowhere to be seen.

Mardi Gras Pass

Fast-forward to the 21st century, and a few miles upriver.

At Mile 43.7 AHP, on the east bank just below Pointe à la Hache, is a relatively new phenomenon called Mardi Gras Pass. It’s a naturally occurring pass that developed in 2011 and 2012, and has started bringing sediment and fresh water into the wetlands and creating new real estate.

The pass started to develop during the high water of May 2011. River water flowing over the natural levee cut a new 630-foot long channel through it. The location is beyond the end of the east bank levee system, so there is no man-made levee.

The water cut through a gravel road, but didn’t go much farther until the following year. In early 2012, during Carnival season, erosion continued and the river water made its way to the existing Back Levee Canal, which connected it to the coastal marshes. Scientists and other observers were there to see it happen, and naturally thought to name it for Mardi Gras.

In 2014, the U.S. Coast Guard determined that the pass was a navigable waterway. In 2015, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names officially named it Mardi Gras Pass.

The pass has grown steadily. A bathymetric survey in November 2017 showed an average depth of 23.7 feet and an average width of 188.1 feet. A better measure of depth is the thalweg, or deep-water channel line, which has an average depth of 40.7 feet.

The pass itself is only 0.85 miles long, but it’s connected to the Back Levee Canal, which sends the river water and sediment through a network of pre-existing canals and cuts into the marsh.

The oyster industry and others are objecting to the new influx of fresh water, and want it either blocked off or controlled and restricted. To do that will require approval from the state as well as from the Corps of Engineers. In the meantime, the pass appears to be building land.

When Mardi Gras Pass formed in 2012, it was the first time in many decades that the Mississippi River had created a new natural distributary. In another Carnival coincidence, the previous time that had happened was probably in the 1960s or 1970s back downriver near mile 20 AHP, just a few thousand feet away from Fort St. Philip and Iberville’s Mardi Gras Bayou.