When we think of valiant fighting vessels, a humble 500-foot-long drydock might not come to mind. But for almost a hundred years, the U.S. Navy had just that, a turn-of-the-century drydock that saw the Mississippi River, the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the Pacific. It was sunk by enemy fire, but was refloated and went on to help win World War II.

In 1891, a U.S. government committee was looking for a Gulf of Mexico-area site for a proposed new drydock. They decided on the Navy’s property on the Lower Mississippi River at Algiers, the west bank of New Orleans, now defined as mile 93 AHP. All other locations visited were either too shallow or not far enough from the sea to be safe from gun fire. The Navy had owned the Algiers location for decades, but had never established a major facility there.

Algiers had had as many as eight drydocks since before the Civil War, and there was still a thriving shipbuilding and repair industry right at and below Algiers Point, but those were wooden contraptions that would not be suitable for picking up the Navy’s new iron and steel ships of war. The Navy intended to have a state-of-the-art steel drydock.

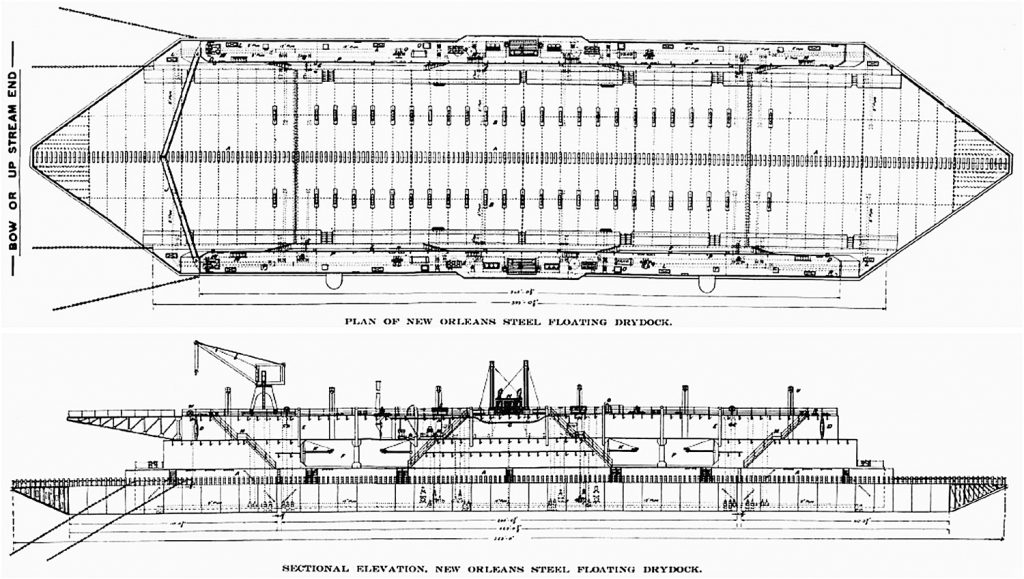

The dock was finally approved by an ct of Congress in May of 1898. The engineers Clark and Standfield of London won the design contract in 1899. They drew up plans for a steel drydock 525 feet long and 128 feet wide, with 100 feet between the walls. The lifting capacity would be 18,000 tons, the highest capacity of any drydock in the world. This seemingly enormous vessel would be built by the Maryland Steel Company at Sparrow’s Point, on the outskirts of Baltimore.

On October 16, 1901, the new drydock was ready and began its first voyage. It was towed to New Orleans, according to one local paper, by “four of the most powerful towing steamers on the Atlantic coast,” the Orion, Taurus, Peerless, and Volunteer, with an “aggregate steam horsepower of 10,000 pounds.”

Welcome To New Orleans

To say that New Orleanians were eagerly anticipating the new drydock would be an understatement. The press heralded the arrival of the “most celebrated piece of naval docking machinery in the world, which will bring to New Orleans the biggest battleships in the United States Navy and make the port of New Orleans a naval station of unusual importance.”

Civic and business leaders acted as if this were the eighth wonder of the world. Mayor Paul Capdevielle asked local employers to give workers a half-day holiday, so that as many citizens as possible could observe and celebrate the arrival of the drydock.

When the tugs and their drydock finally approached New Orleans on November 6, 1901, there was a river parade consisting of the training ship USS Stranger, then a flagship steamboat carrying the governor, the mayor and drydock committee, then three columns of vessels, six long. There was a street parade in Algiers afterward, with 10 carriages carrying the governor, two U.S. senators, members of the City Council, Rep. Adolf Meyer, and the mayor, followed by bands and marching groups from labor unions ranging from the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen to the Ship Carpenters and Joiners of Algiers, to the Boiler Makers & Iron Shipbuilders Union. Near the ferry landing at Algiers Point, there was a reviewing stand.

Meanwhile, the public was clamoring for an up-close view of the new wonder. Citizens on the east bank crowded the ferries and even paid fishermen to bring them over to Algiers.

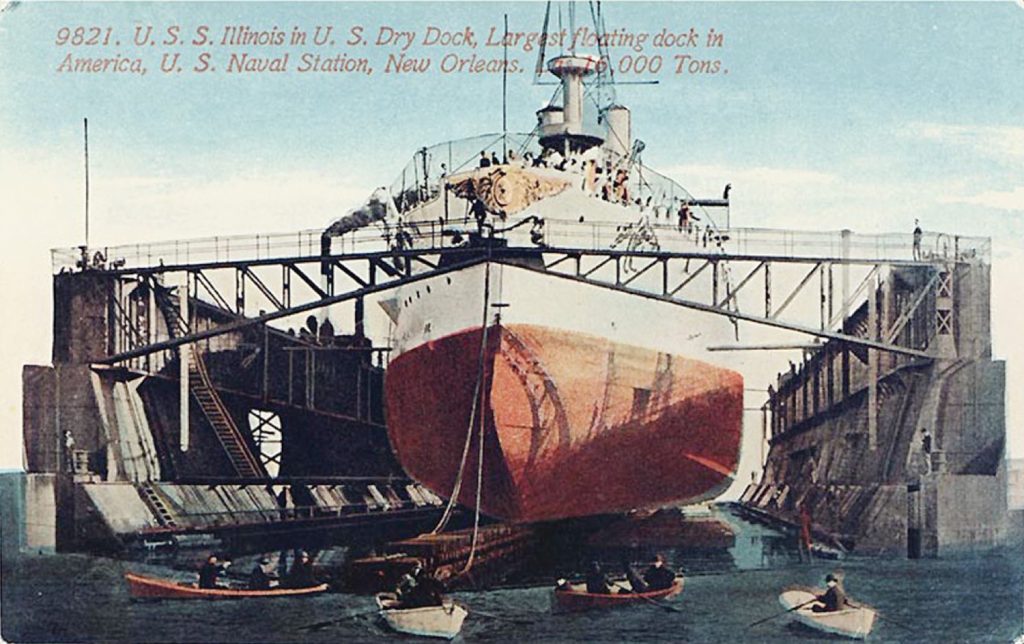

It took two months to get the drydock positioned and secured and ready for business. On January 6, 1902, it was tested by lifting the newly commissioned 11,565-ton battleship USS Illinois.

Shipping interests and the local business community—even the private drydock operations just up the river road—were eager for the Navy dock to be up and running. The reason was that New Orleans did not have a large enough drydock for many of the larger commercial vessels. Foreign ships visiting port with repair needs had to make their way to Atlantic Coast ports. The Navy had agreed that their new steel drydock could be “hired out” when not being used for government ships.

Once the battleship Illinois had been raised and lowered with no problems, the first “paying customer” was waiting right next door at the Southern Pacific Railroad yard. It was the steel-hulled transfer boat Carrier (see WJ, July 24, 2017). The Carrier’s hull had been in the water since its launching almost 10 years earlier. At about 300 feet long and 72 feet wide, there was no local facility large enough to raise it.

By 1909, the Algiers Navy yard had a traveling steam crane with a 30-foot boom, a 3,000-foot wharf, a locomotive and several rail cars, two machine shops, and a foundry. During World War I, the drydock and Navy yard were used for repair and overhaul of gunboats, New Orleans-class cruisers, and other vessels working in the Gulf and the Caribbean.

During this period, the drydock acquired a name, of sorts. The Navy started classifying drydocks of the Algiers variety as Yard Floating Docks, or YFD. The Algiers drydock was designated as YFD-2.

Move To The Pacific

Just a few years after the end of World War I, naval business slowed down, and by 1938 the Algiers naval workforce was down to 13 men. The drydock itself was only occasionally used. There was a proposal to get the yard turned into a base for decommissioned ships.

But in 1939, Franklin Roosevelt’s administration decided that the Algiers drydock was needed at Pearl Harbor, to supplement the inadequate docking facilities there. It would be an awkward 6,000-mile voyage, but the Navy had experience with a job like this: more than 30 years earlier, it had towed another drydock from the East Coast via Suez to the Philippines.

On November 17, 1939, the Navy awarded a $163,800 contract to Todd-Johnson Dry Docks Inc., just up the road, to prepare YFD-2 for towing. About 500 tons of steel beams were added to the hull to increase rigidity. A bow coaming of oaken planking reinforced by steel was built on one end. Quarters for the crew of 22 men were built in the walls. Four battleship anchors, a two-way radio, and a library were added. New storage tanks were filled with oil for the tugs, and coal was stacked on deck.

On March 19, 1940, after 39 years at Algiers, YFD-2 began a 6,000-mile journey to Hawaii. Three Navy tugs maneuvered the drydock off the west bank and headed downriver. The tugs were the Willet, Relief, and Peacock. All told, the trip was expected to take about four months, plus a possible stop at a West Coast port.

At Cristobal, at the eastern entrance to the Panama Canal, the 128-foot-wide drydock was taken apart and towed through the canal in sections. The lock clearances at that time were 110 feet. The drydock was reassembled at Balboa.

The flotilla arrived at Pearl Harbor on August 23, 1940, and YFD-2 was soon put to work. It could lift all but the largest of the Navy’s ships, and did so for more than a year with no problems. Sailors at Pearl Harbor soon gave the drydock the nickname “Old New Orleans.”

The destroyer USS Shaw was in YFD-2 on December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Most of the crew of the Shaw were ashore, so only a few men were on hand when the bombs started to fall.

The Japanese strike force attacked the naval base shortly before 8 a.m. The first wave of torpedo planes and bombers targeted the battleships, but the next wave hit the Shaw.

At 9:12 a.m., the Shaw was hit by three bombs from steep-diving planes, from an altitude of about 1,000 feet. Two 250-pound bombs hit the forecastle and went through the main deck and the forward machine gun platform and exploded in the crew’s mess hall. A third 250-pound bomb went through the port wing of the bridge and exploded in the wardroom pantry, rupturing the fuel oil tanks.

By 9:25, all of the Shaw’s firefighting capabilities were completely depleted, so the order was given to abandon ship. The officer in charge, Lt. James H. Brown, went to the drydock headquarters demanding to have YFD-2 flooded so that the destroyer could float off and fight. Lt. Brown, however, couldn’t make it back to the Shaw. Burning fuel oil had flowed under the dock’s wooden keel blocks, setting them on fire.

Shortly after 9:30, the Shaw’s forward magazines blew up. The blast shredded the ship’s superstructure and ripped off part of the bow. The explosion also holed YFD-2, and the drydock started to sink.

Efforts to flood the dock and extinguish the fire were only partially successful. As YFD-2 sank, the Shaw’s bow fell off to starboard and went under with the dock. The Shaw then toppled off its blocks into the water, but remained afloat. As YFD-2 submerged, flaming oil swirled around the destroyer. Survivors had to swim through patches of smoking oil. The Shaw lost 25 crewmen in the attack.

Heavily damaged as it was, YFD-2 was raised and repaired. The job was carried out by the base force under the supervision of the Pacific Bridge Company, which diverted some of its divers and equipment from other work it was contracted for at the base. Divers plugged or welded up more than 200 holes in YFD-2 to make it watertight. The drydock was finally pumped out and raised on January 9, 1942. It had been sitting on the bottom for more than a month, listing at a 15-degree angle or more. The repairs were temporary, though, just to get the thing floating. The drydock was not yet usable.

To make more permanent repairs, the Pacific Bridge divers installed a 40-square- foot patch under the hull to create a chamber, four feet deep, to allow repairs to the frames and bottom plates. This prevented YFD-2 from having to be put into a larger drydock for repair.

YFD-2 was put back in service on January 25, 1942, but only on a limited basis. It did not yet have full buoyancy because of one more large hole that the divers had not repaired. But it could lift a destroyer. The next day, that destroyer was USS Shaw again. Shaw was in the dock for 10 days to get a new bow for its voyage to the naval shipyard at Mare Island, Calif., for more substantial repairs.

In May of 1942, hull repairs on YFD-2 were completed and it was fully operational again. It provided an invaluable service, facilitating the repair of other vessels damaged in the attack, and then working in support of the Pacific Fleet through the rest of the war in the Pacific. More than 50 vessels were serviced by YFD-2 in 1942 alone, and at least another 70 in 1943.

In December 1943, the bomb disposal unit at Pearl Harbor was called in when four unexploded 5-inch shells and five unexploded 38-calibre shells were discovered in one of the lower tanks of the drydock, having been there since the Japanese attack two years earlier.

In the year 2000, “Old New Orleans” was transferred to the Dominican Republic, ending almost 100 years of service to the U.S. Navy.