For the most part, life aboard a towing vessel is marked by separation from friends and family. It’s a natural and necessary part of a job that can be both dangerous and 24/7. While technology may have eased that sense of detachment of late, a phone still can’t replace physical presence.

Frank Banta Sr., 93, of Sunshine, La., and his wife, Dorella, remember a time when the life of a towboater could be different, though.

Some of Frank Sr.’s earliest memories are of his father, J.W. Banta, clearing drift for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, then going to work aboard the famed steam-powered sternwheel towboat Sprague. That was in the early- to mid-1930s.

“That was with Standard Oil,” Frank Sr. said. “He was a cub pilot. They were running between Baton Rouge and Memphis. That’s the first memory I had of him.”

Frank Sr. said his father would bring lines home so that he and his brothers, Merlin and George, could make lassoes and pretend to be cowboys.

Soon, J.W. partnered with Al Grace to buy an old ferry boat, the Polly S. First on the to-do list for the Polly S was swapping out the gasoline engine for a 100 hp. Kahlenberg diesel.

“He put that motor together piece by piece,” Frank Sr. said. “When he couldn’t get his hand in there because it was too big, he’d use mine.”

That wasn’t the only way J.W. involved his children in the everyday work of his newly formed business, Pelican Towing Company.

“He would take pennies and nickels and spread them around in the hull,” Frank Sr. said. “The hull was full of mud. As we went looking for the money, we’d throw the mud overboard and keep the money.”

In those days, one of J.W.’s jobs was to catch driftwood in the spring, trim it up, then bring it to a local sawmill for timber.

“We still get a little drift coming down the river,” Frank Sr. said, “but not near as much as we used to.”

Around the start of World War II, J.W. bought the mv. Anita D, and that’s the boat where Frank Sr. and his brothers really began to gain experience as mariners.

“In the summer vacation, we’d spend the whole three months of vacation working on the boat,” he said. “And we weren’t on the payroll. We were just working.”

Frank Sr. said his first job was “engineer,” working down in the engineroom and responding to “bells and whistles” his father would send from the wheelhouse.

“They called me an engineer, but I wasn’t,” he said. “All I could do was start and stop the engine.”

The years went on, and Frank Sr. gained experience as pilot. Then, there came the day he asked for a raise.

“They wouldn’t give me a raise, so that’s why I went to work for Baton Rouge Coal & Towing Company,” he said. “They gave me a raise, and they’re the ones that put me in the wheelhouse.”

Frank Sr. explained that, at that time, mariners only needed a license if they were piloting a steamboat. On a diesel-powered towboat, no such license was required.

As it turned out, Frank Sr.’s time with Baton Rouge Coal & Towing was short. He only worked there for a summer before J.W. hired him back—as a pilot and with a raise.

By the start of the 1950s, Frank Sr. launched out on his own in a couple of different ways. In 1951, he and Dorella got married.

“He was every bit of 20, and I was every bit of 17,” Dorella said. “We thought we could [take on] the world, like most young people. We’ve had some good times and bad times, like every other one.”

Frank Sr.’s cousin was married to Dorella’s sister, and one Sunday they brought Frank Sr. from Plaquemine to White Castle, La., for an afternoon of fishing.

“That’s when we came in that Model T,” Frank Sr. said.

“I could hear them coming halfway from Plaquemine to White Castle,” Dorella said.

They both laughed at that memory.

Frank Sr. said they took the Ford Model T that day on account of the poor, muddy road conditions.

“There really was no road,” Dorella said. “It was just a passageway.”

Also around that time, Frank Sr. and his brothers George and Merlin launched Plaquemine Towing Company, which primarily moved barges on the upper and lower Mississippi and along the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway. Dorella said that from the start she made accompanying Frank Sr. on the boats a priority.

“I came home to have my babies. Then we all went back on the boat,” she said. “That lasted until the oldest one was six. Then, we’d go in the summertime.”

The couple went on to have four children: sons Frank Jr. and Robert; a daughter, Eugenie, who passed away just last year; and Jamie, a son, who died when he was a boy.

In the 1950s, Plaquemine Towing Company’s mv. George W. Banta was working for Cargill, pushing empty hopper barges to the Upper Mississippi River, then bringing loaded barges down to Louisiana. Going upstream, the young couple found creative ways to amuse the children and pass the time.

“I would pump 2 or 3 feet of water in an empty hopper barge, and that was their swimming pool,” Frank Sr. said. “When we’d go upriver, she’d go out there with her folding chair and a book and read while they swam. We had a pirogue on there too, and they’d put that in there and paddle around.”

“I didn’t have to worry about them falling overboard because we had a 9-foot wall around the barges,” Dorella said. “They could play and do just about whatever they wanted, running around and burning up some energy.”

“We had some good crews too,” Frank Sr. said. “They’d take care of the kids.”

The George W. Banta had jack-and-jill staterooms with a shared bathroom. The kids slept in one stateroom, while Frank Sr. and Dorella stayed in the other.

“We even spent a Christmas on the boat,” Dorella said. “We had a Christmas tree, and Santa Claus came to visit, and all those good things.”

It wasn’t all fun and games for the Banta kids. Just like his father did for him, Frank Sr. introduced his children to the work of a mariner from a young age.

“When did they start working for me?” he said. “When they were old enough to hold a ratchet.”

Later, if Frank Sr. got a call to service a ship or shift barges in the middle of the night, Frank Jr. and Robert would go along, too.

“I’d get one or both of them up to be my deckhands,” he said.

Both Frank Jr. and Robert grew up and eventually launched their own businesses. Frank Jr. started Chem Carriers in 1994 and soon acquired the assets of Plaquemine Towing Company.

“Frankie was very active as a young boy in the company,” Dorella said. “It was almost a natural thing for him to buy the company when he did and take over. It was in his blood.”

Robert later joined Chem Carriers, and he now serves as port captain.

Looking at the growth of Chem Carriers, which now owns 15 towboats and 54 barges, Frank Sr. and Dorella said it’s easy to be proud of Frank Jr. and Robert.

“They’re very successful at everything they do,” Dorella said. “Not many people grow up on the river itself.”

Like Pelican Towing and Plaquemine Towing, Chem Carriers in many ways is a family business. Their sons Frank Jr. and Robert are there, as is their son-in-law Steve LaPlace, the company’s accountant. Ben Hays, Frank Jr.’s son-in-law, serves as Chem Carriers’ chief operating officer.

“We even had some cousins we made boat people out of, too,” Frank Sr. said.

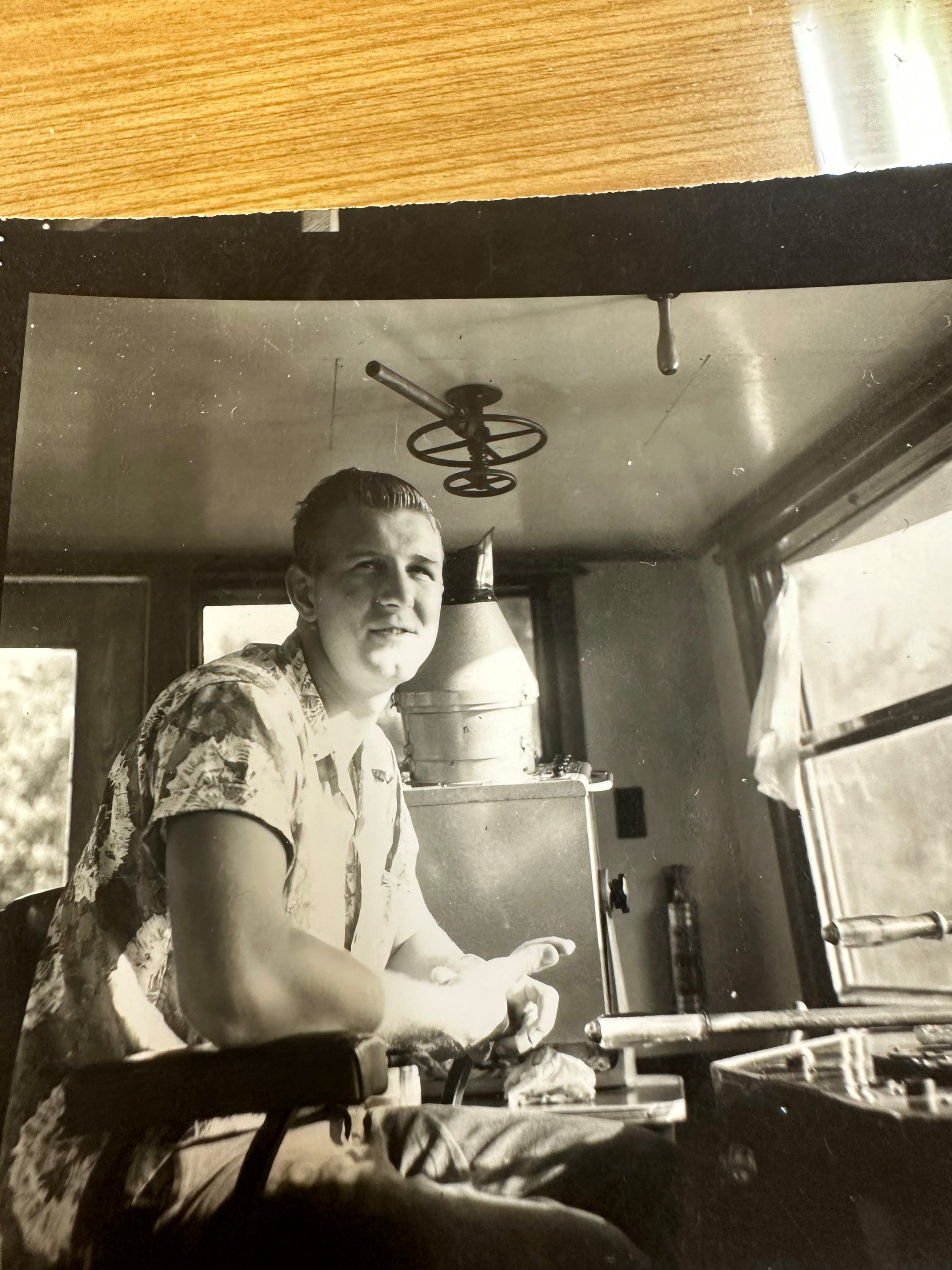

Looking through a scrapbook of mostly black-and-white photos is like looking through a window to a simpler time, Frank Jr. said. As he lived it, he had no idea the impact it was having.

“I’m really grateful I had the lessons I had,” Frank Jr. said. “I guess it was a need for them to have extra help, but it was a learning curve I didn’t know I was getting.”

Today, even though Frank Sr.’s license is no longer active, he and Dorella are still connected to the family business. Their home of 60-plus years sits adjacent to the Chem Carriers office in Sunshine, La., and Frank Jr., Robert and Steve all live nearby.

“So we’ve lost two children, but Frankie and Robert are very good to us,” Dorella said. “They come to see us four or five times a week at least. … We’ve had a good life.”